Stakeholder Accountability

Welcome to the fourth of five blog posts about Imperative 21’s audacious plans to “reset” the American and global economy which consists (not surprisingly given its name) of three imperatives, each of which has three sub-imperatives.

This one deals with the third—stakeholder accountability–which might seem to take us into wonky economic territory at first glance. As you will see in the rest of this post, the Imperative 21 defined this one in more explicitly economic terms than it did when developing the first two.

However, as I dug into it as a peacebuilder and a political scientist, I realized that its implications weren’t wonky or narrow at all, because they brought me to some of the sweeping reforms that the crises of 2020 have forced onto the public agenda in four ways which I’ll lay out in the rest of this post.

- As you will see in the next section a capitalism that takes the interests of all stakeholders forces us to base our thoughts and actions on far more than conventional versions of business and economics.

- We should have seen that before COVID-19 hit. There is no need to beat ourselves up over that failure. However, if we are going to take the responsibilities that come with stakeholder capitalism seriously, we will have to change much of what we do starting with the ways we determine success and failure.

- The new definitions of accountability thee imperatives lead to also make a lot of sense for a world of wicked problems in which our problems are so interconnected that you can’t solve any of them separately, easily, or quickly, if you can solve them at all.

- Last but by no means least, accountability is the piece of the Imperative 21 argument that we can begin taking action on without a change in administration, new laws being passed and the like.

The Imperative 21 Series

Stakeholder Accountability

Your Content Goes Here

Stakeholders ≠ Shareholders

The two words in this section’s title have ten of their twelve words in common. Those two letters make all the difference. For this post and for a whole lot more.

As I mentioned in earlier posts in this series, Imperative 21 used the fiftieth anniversary of a famous New York Times article by Milton Friedman on shareholder capitalism to launch its campaign to reset the twenty-first century economy. In it, he argued that corporations and their leaders only had one goal—to turn a profit. Even before then, the pursuit of what is known as shareholder values has been at the heart of economic theory and legal practice.

Business leaders and others who understand that we live in a complex and totally interdependent world have long understood that pursuit of any single goal that privileges any one actor is counterproductive for the entire system especially over the long haul. In peacebuilding where I now spend the bulk of my time, we tend to talk in terms of win/win outcomes, reconciling long-term divisions, and solving conflict by addressing its root causes.

That’s the case because the mainstream, Friedmanesque version of the firm privileges profit and, through it, only a single kind of capital—financial. And even that has changed. In the not-so-good old days, financial capital brought stable ownership as reflected in the family names that corporations bore from Ford to Rockefeller to JP Morgan to Cadbury and, eventually to Ben and Jerry.

That has changed. Financial capital and ownership now lies primarily in institutional hands in the form of hedge funds, venture capitalists, and the like. It is also fleeting to the point that few companies—like Ford—can claim a direct lineage from its founders to its current owners. In other words, today’s owners rarely have anything but financial “skin in the same.”

Even more importantly, focusing only on financial capital means we ignore its other forms—human, environmental, and even generational—which should lead us to see that anyone who is part of a company’s ecosystem has a stake in its future. That iw what economics have in in mind when they talk about stakeholder rather than shareholder values.

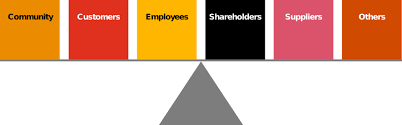

Oxford’s Colin Mayer, for example insists that corporations have multiple purposes of which making a profit is only one. In his recent book, Prosperity, which I’ve reviewed elsewhere, he argues that their leaders have many constituencies, of which their own pocketbooks are only one. Thus, when they talk about stakeholder capitalism, they refer to everyone whose interests are touched by the corporation, including, of course, its owners, but also its workers, customers, suppliers, the environment, and, even, its competitors. Perhaps because they have their roots in systems and related theories, they tend to downplay the importance of short term profit and loss as seen, say, in stock market fluctuations and focus instead on the company’s and everyone else’s long term economic health. Or, put in its simplest terms, the image at the top of this post shows that accountability in stakeholder capitalism is a giant balancing act in which a company’s owners and managers at least should look out for the interests of every single one of their constituents.

The Accountability Imperatives

In the last two posts, I focused on Imperative 21’s long term goals in dealing with design and investment. Both could allow us to think solely in terms of longer term goals and aspirations. Accountability forces us to deal with at least two down to earth questions.

First, the word itself conjures up the image of the accountant who calculate profits and losses and the overall composition of a company or a country’s balance sheet. Second and more importantly, accountability refers to our ability to literally hold authority figures—including corporate and political leaders—accountable for their actions which, as you’ll see, helps us hone in on the choices we make and the reasons why we make them.

Accountability in both senses will be needed as we build an economic system that serves people and stewards our natural resources for future generations. Business needs to be accountable to all of its stakeholders, from workers to investors to local communities, balancing diverse interests and reporting on its choices and progress as the image at the top of this post suggests.

We individuals have to be held accountable, too. Even though our decisions affect our admittedly smaller ecosystems, we can’t ignore the implications of our actions either.

In short, I would go beyond Imperative 21’s core statement and suggest that accountability applies across the board to us all.

A New Fiduciary Duty

That starts with the ways owners and boards of directors define their jobs. Most of us take for granted that everyone from those of us who own stock in companies to a university’s boards of trustees who manage its endowment want to maximize the financial return on our investments. In fact, the courts and most economists have gone so far as to enshrine short term return on investment as their fiscal obligation.

On one level, I get it. The colleges I’ve attended and worked at, for example, are all strapped for cash. The money they make from their endowment matters, especially now with the added costs they face given the pandemic.

However, in an interdependent world, they also have other responsibilities. I’m a veteran of 1980s debates over divesting stock in companies that operated in South Africa. Today, we are worried about a broader range of issues that our investments have a bearing on—climate change, the status of people of color, economic inequality, and more.

Whether I’m managing a college’s investment portfolio, running a multinational company, or simply deciding where to invest my own pension funds, I should be taking the impact of those investments into account on everyone and everything. And, once we redefine our fiduciary duties to include everything from the environment to social injustice, we will compel business and investors to be accountable for their impact on all stakeholders and to steward our natural and social systems.

New Incentives

Even more than the Imperative 21 team, Mayer focuses on the fact that big companies are increasingly owned by large pension and investment funds that may not hold on to their shares for very long. That has spearheaded everyone’s growing interest in shareholder capitalism, especially making profit quickly, most notably as reflected in quarterly profit and loss statements.

Those incentive systems are not etched in stone and reflect a series of regulations and other policy changes made over the years. Some will require dramatic shifts in the way corporate law is written.

However, we should not ignore the fact that some companies have decided to change the way they operate on their own. So-called Benefit Corporations are now legal in 35 American states and a number of other countries. Unlike traditional companies, they adopt goals that include providing social “benefits” as well as making a profit. In them, boards of directors assess a company’s performance in reaching all of its stated goals and not just how much money it has made for its investors.

As of early this year, 3,000 companies in 150 industries and 70 countries have been certified as B corporations by the B Lab which is one of founding members of Imperative 21. Thousands of others exist but have not sought the certification that the B Lab offers.

Many B corporations have explicitly environmental goals as part of what is often referred to as their triple bottom line, which adds people and planet to profit. Most eschew a singular focus on short term results preferring to seek and reward investments that create sustainable social and environmental value, alongside financial gain. Likewise, business and investment that produce negative externalities need to bear those costs, rather than push those costs on to the balance sheet of citizen-taxpayers.

New metrics

Accountants have spent centuries developing statistical and other tools for measuring a company’s success or failure, including its ROI or return on investment. Unfortunately, they have only done so for what Mayer calls financial capital even though a company’s or a country’s fate depends on all of its investments and all of its inputs.

That we expand the way we measure accountability is not new. For decades, ecologists have argued that measures like gross national product miss the environmental consequences of our action. In the last few months, we have been reminded of those non-financial costs and consequences as we’ve tried to add up the costs of systemic racism in the poverty of American inner cities or in the human toll taken by COVID-19 in communities of color.

While we are far from having the elaborate accounting schemes we find among CPAs, more and more companies are developing new metrics that can help them measure progress they are making toward a more sustainable future. That can be as simple as penalizing companies for their contributions to environmental decay as well as allowing them to deduct the depreciation of their own physical assets from their tax bills.

In the wonky world of accountants and economists, that means including “exernalities” like environmental decay or the conflicts that grow out of an unequal distribution of wealth in a company’s or a country’s balance sheet. sPut simply, the wellbeing of the planet and all of its inhabitants need to be valued alongside financial returns. Metrics must therefore reflect the totality of financial, social, and environmental performance.

Next Steps

I’ll explore how we can make all of this happen in my next post that will cover:

- Imperative 21’s own campaign to shift corporate culture and public policy in the United States and beyond

- What those of us who are not part of the business world but think of ourselves as allies can do to advance causes like Imperative 21’s

- How the upcoming American presidential election fits into all of this

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.

Also published on Medium.