Using Improv to Work With Those We Disagree With

In his class, Doug Irvin-Erickson gave his grad students an assignment half way through the short summer semester. He broke them into teams and asked them to make presentations to the class on how peacebuilding and human rights overlapped—or didn’t as the course may be. Because I had had to miss the previous class, the students had decided that I would serve as a discussant and respond to each project.

During the course of the semester, we had mostly focused on how the two fields differ. Human rights advocates focus on rights that they assume to be universal and innate—and all too often denied by the powers that be. Peacebuilders, by contract, try to build agreements among all parties to a dispute, including those that limit some people’s human rights.

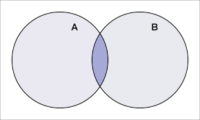

Intersection Sets

The three groups did a remarkable job of seeing how little overlap there is between what the two communities do but how much there could and should be. One of them actually drew a Venn diagram of the two fields showing a very small intersection set suggesting that there is next to no overlap between them.

This is a problem we run up against almost any time peacebuilders who have a background in consensus building try to work with colleagues who come from an advocacy background, especially one that focuses on rights, inequality, injustice, and the like. Often those discussions don’t go very far.

The other night, we did take the discussion farther by focusing on what is resented here as the tiny area of overlap when we asked two questions:

- What do we already do in common?

- How can we expand the “size” of the intersection set so that we can cooperate more?

We do tend to cooperate, in particular, when the focus is less on human rights law and more on creating and then reinforcing support for them by building agreement on new norms. We spent a lot of time on the history of both the civil rights and same-sex marriage movements and realized that there was a constructive interplay between people advocating legal change and those working at the local level and beyond to sway public opinion around what Daniel Yankelovich used to call new public judgments.

No, And

Meanwhile, I’ve been thinking about a more general question. How does a peacebuilder who also has strong position on the issues he or she is dealing with work with people on the “other side?” In the class, we had mostly dealt with this question in rather abstract and hypothetical ways. How would you deal with Donald Trump or someone else you disagreed with strongly? If our class was filled with conservatives rather than liberals, that question would have revolved around Barack Obama or someone else on the left that they found polarizing—and wrong.

Meanwhile, I’ve been thinking about a more general question. How does a peacebuilder who also has strong position on the issues he or she is dealing with work with people on the “other side?” In the class, we had mostly dealt with this question in rather abstract and hypothetical ways. How would you deal with Donald Trump or someone else you disagreed with strongly? If our class was filled with conservatives rather than liberals, that question would have revolved around Barack Obama or someone else on the left that they found polarizing—and wrong.

I can put the question more succinctly by breaking it down into two parts:

- How do I disagree with someone under conditions like that, and

- How do I do so and increase the size of the intersection set between us.

So, I tried out an idea I’d been working on and expanded while we discussed their presentations which is outlined in the table below which, in turn, is based on a loose reading of the way Second City uses improv to help organizations function better. Second City’s ideas are reflected in the top row.

| But | And | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | Academic and other disagreement | Improv |

| No | Deepending disagreement | Potential for finding common ground |

Yes, but. All too often we react to an idea we sort of agree with by also finding fault with parts of it in ways that tend to make it hard for us to move forward. We academics are particularly good (or is it bad?) at this.

Yes, and. This is the core of improv. Whatever the first person says, the second (and subsequent) member of the ensemble, says yes, and adding something to the original idea. Second City’s goal in their shows is to come up with hilarious skits. In their consulting work, they use yes, and along with some other tools to help a team come up with creative ideas and develop ways of working together.

The more activist students had resisted this idea a bit when I first raised improv in class earlier in the term. Listening to them in the presentations led me to add the second row which breaks one of the key rules of improv (by saying no) but keeps its other principle (by adding and). That could expand the size of the intersection set.

We peacebuilders are often criticized for being too willing to work with people we disagree with and not make it clear just how deep those disagreements are. That’s probably the case, because we all have plenty of experience with one of the cells in that bottom row, but not with the other which.

No, but. This is the kind of statement one usually hears in a debate. I disagree with you and then go on and show you exactly why I think you’re wrong. In the class, we’ve come to call it naming and shaming, which is something the human rights community (and other activists) have done a lot of. In the cases we’ve looked at this semester, that has been done on the side of the issue(s) I agree with. That, however, does not make it constructive.

No, and. By contrast, this is the kind of sentiment one rarely hears in a heated debate. Like the “and” in “yes, and,” it invites the other participants to seek slivers of common ground and thereby can expand the intersection set.

When I thought about it, I can never remember a time when I have used the exact words, “no and,” nor could I think of times when I would actually do so. However, I’ve realized that the sentiment underlies almost all of the world I’ve done with Evangelical Christians, members of the military, and others I disagree with over the years. When necessary, I make it clear where we disagree (the “no”), but I also invite them to explore ways we can still work together.

I’ve seen this work second hand on some tough issues. In particular, Public Conversations (now Essential Partners) led an extended series of discussions with pro-choice and pro-life activists in the 1990s. The activists did not convince each other. However, by using variants on what I’ve just called “no, but,” they were able to both develop a good deal of respect for each other and agreeing on some policy proposals, including those that would reduce the rate of teen pregnancies.

The students correctly pushed back some, arguing that they could not use this kind of an approach in work with KKK members and the like. I agree. However, I can’t imagine a time in which I’d be ask to sit down with white supremacists like the ones who chanted “Jews will not replace us” in Charlottesville. As a Jew, I would find doing so all but impossible.

However, I have found that using techniques that resemble “no, but,” I have been able to develop working relationships and even friendships with people I disagree with. We all changed as a result. The most recent example came when I attended the first national meeting of Evangelicals for Peace right after the 2016 election. They disagreed amongst themselves, while I disagreed with most of them on some key issues such as the choice/life debate. However, I watched them “no, but” each other a lot (and pray a lot) and I saw them reach agreement on what they could do together to deal with the issues that were likely to come up during the Trump presidency.

In other words, “no, and” will not work all the time. But if nothing else, it’s worth exploring in more detail.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.

Also published on Medium.