Rethinking Power

It’s about time for us to rethink what power means. I’ve felt that way for some time especially when I’ve had to think about the ways in which my work as a peacebuilder and as a political scientist do not mesh. It took reading Dacher Keltner’s The Power Paradox to have the pieces begin to fall into place.

Keltner is a social psychologist who understands the traditional definition of power we political scientists have used at least since the time of Machiavelli. As Robert Dahl put it in the 1950s:

A has power over B to the extent that he can get B to do something that B would not otherwise do.

In other words, power implies at least the threat of force. That force need not be violent. It could be economic or psychological, but if I’m B, why would I do what you (A) want me to do otherwise?

Keltner understands that the world has changed to the point that the social center have gravity has shifted toward networks in what professors at the Army War College started calling a VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous) world in the late 1990s.

In that kind of a world, the kind of power Machiavelli and Dahl (and most political experts in between) talk about tends to be counterproductive in the long run. Because everything I do affects you and vice versa, what I do “today” comes back and affects me “tomorrow.” What goes around literally does come around.

To be sure, political scientists have added some nuance to the traditional definition. Pluralists and others (including Dahl himself) realized that few American politicians have the power to do everything they want. Since Dahl’s day, too, some international relations experts have been stressing “soft” power that relies on diplomacy and the like. But, it’s still power in the sense that my government is trying to get your government to do something it doesn’t want to do.

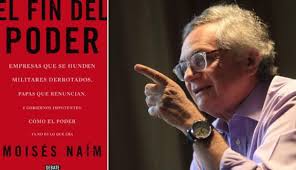

Still, as Moises Naim puts it in The End of Power, traditional forms of power are fleeting because they are not taking us very far toward solving key “wicked problems” whose causes and consequences are so inextricably intertwined that they cannot be solved quickly, easily, or separately if they can be solved at all.

While Naim does not probe alternatives to old-style power very much, Keltner does. His lab has spent the last twenty years investigating what power is like in networks and other relational structures. In particular, he makes the case that It comes from empowering others in social networks which occurs when we are empathetic, sharing, giving, express gratitude, and by sharing empowering stories with others that mobilize and empower them. By contrast (and here’s where his idea of a paradox comes in to play), once we have accumulated power, we then tend to act in Machiavellian kinds of ways, and our power tends to evaporate as a result of those very powerful actions.

Keltner does not try to develop those alternatives for national level institutions or policy questions. After all, he is a psychologist who does his research in a lab.

Nonetheless, political scientists would do well to pay attention to how we in the peacebuilding world devise projects that empower people in Keltner’s sense of the term. That’s what we at the Alliance for Peacebuilding are trying to do as we add domestic issues to the global ones our members have worked on since we were create at the beginning of this century. Among the issues we are working on that rarely find their way into conventional political discourse are:

Nonetheless, political scientists would do well to pay attention to how we in the peacebuilding world devise projects that empower people in Keltner’s sense of the term. That’s what we at the Alliance for Peacebuilding are trying to do as we add domestic issues to the global ones our members have worked on since we were create at the beginning of this century. Among the issues we are working on that rarely find their way into conventional political discourse are:

- How can we ease the tension between left and right?

- How can we help policy makers develop policies that benefit most of American society?

- How can we help Americans (and people around the world for that matter) to regain trust in their leaders and institutions?

- How can we help policy makers and average citizens alike see that the problems we face amount to what philosophers call superordinate goals that can only be reached if all or most parties work together to find cooperative solutions.

- Finally, I see all this in my own writing. In my comparative politics textbook, these themes appear more or less as an afterthought in the final chapter. In the conflict resolution and peacebuilding textbook I’m writing now, they appear in the first few pages.

I had dinner over the weekend with a good friend who has stayed (happily and productively) in the academic world. But as we talked, Val began to see why it makes sense to think of power both in traditional and these new and relational terms.

Also published on Medium.