What Kind of Recovery?

Regular readers of this blog will already have realized something I had been reluctant to admit to myself.

I will be writing either a book or its online equivalent on what we could and should do to recover from the crises of 2020. The book will be anchored in what people around the United States are doing and go on to outline a broader strategy for turning what are by definition limited efforts into the kind of paradigm shift I’ve been ranting about for decades..

I was reluctant to take this project on for two reasons. First, I’m over seventy and I wasn’t sure I had another book in me. Second and more importantly, as the crises unfolded over the last six months, the challenge of writing about what we could and should do came to seem insurmountable.

Nonetheless, I’ve come to a few conclusions that suggest that I can write such a book because I can now see multiple paths toward a recovery from those crises that will make us all better off:

- A paradigm shift might be on the table. The situation we face in July 2020 is dire. Nonetheless, the interconnected nature of the crises has had the surprising side effect of making profound change possible in ways I’ve seen before.

- Some cool initiatives. If I’m right, the impetus for making those social, political, economic, environmental and other changes won’t start with our leaders. The pressure to change will have to be based on initiatives begun by average citizens who adopt new norms and build new movements in their neighborhoods, workplaces, and communities. Some have already been started. More importantly, I am part of a number of networks that can help the existing ones grow, incubate even cooler additional initiatives, and amplify the impact that they all have.

- Going to scale. None of them alone will change the world. Together, they just might. There is no reason why we can’t build on what is already taking place and launch a flurry of new “bottom up” initiatives that can be taken to scale and lead to the widespread adoption of new cultural norms and the implementation of sweeping public policy changes.

- Beyond my comfort zone. I’ve been a political scientist and peacebuilder for half a century. I’ve always claimed that we have to bust out of the silos we work in. However, I’ve rarely (fully) practiced what I preached. Until now. While I should have realized it before, the crises we face today are so wide-ranging that we all have to get out of our personal and professional comfort zones and reconsider a lot of what he had taken for granted for so long.

Thank You, Professor Hyman

To be honest, it took me four months of crisis time to get this far.

To be honest, it took me four months of crisis time to get this far.

Like most people I know, I had a hard time convincing myself that we could define what that path forward was in ways that were simple enough and powerful enough to pull millions or even billions of us from our sense of fear and powerlessness.

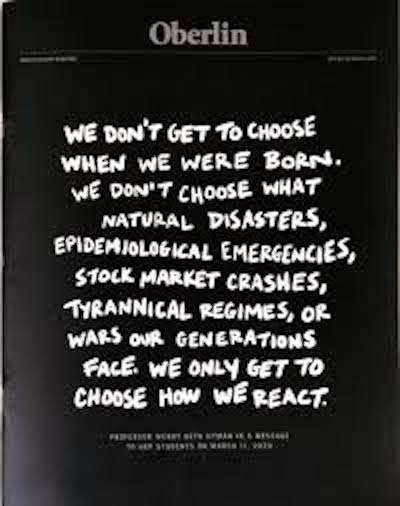

Then, ten days ago, I pulled the most recent Oberlin Alumni Magazine from three-day-mail-quarantine bag and saw these words by English professor, Wendy Beth Hyman, on the cover.

We don’t get to choose when we were born.

We don’t choose what natural disasters, epidemiological emergencies, stock market crashes, tyrannical regimes, or wars our generations face.

We only get to choose how we react.

In three sentences, she not only gave me the question to ask in order to reach my other goal which I drew from Kelly Corrigan’s remarkable segment on the PBS Newshour—nailing it.

From Holistic Crisis to Paradigm Shift

Perhaps because the pandemic and the recession had such a sudden and global impact and then were followed by equally sudden and all but global response to George Floyd’s murder, we are more open to sweeping changes than we were a mere four months ago.

I was convinced of this first point by a new book from (to me) an unlikely source. I rarely take the pronouncements that come out of the Davos World Economic Forum all that seriously. Although the rich and powerful people who gather there do discuss important issues, those discussions rarely amount to much.

I was therefore delightedly surprised when I read its new book, COVID-19 Reset which was published last Friday and I have reviewed elsewhere. Written very quickly by Davos CEO Klaus Schwab and systems thinker Thierry Malleret, the book is an amazingly deep discussion of how deeply rooted the problems we face are and how sweeping our response to them will have to be to the point that “reset” is probably too simple a term to use in describing it.

Schwab and Malleret understand that the pandemic’s cascading effects have changed things so much that we couldn’t go back to the “normal” life we lived as recently as March. Instead, they assume that we will have to make an equally far-reaching reset of our basic institutions and their practices. They make that clear at the end of the first paragraph.

A new world will emerge, the contours of which are for us to both imagine and to draw.

They then lay out a series of changes that the kinds of people who attend the Davos conference can actually help pull off at the global, corporate and individual levels.

Their diagnosis reflects the fact that the pandemic has had cascading effects that have touched the lives of just about everyone on the planet in irreversible ways.

More importantly, they make the case that their readers–in other words, some of the world’s wealthiest and most influential individuals–have to lead a rebuild or reset in a way that addresses all of the issues that have crashed to the surface since the first cases of COVID-19 were reported at the end of 2019. Sustainability. Addressing inequality. Protests around race and gender and the demands of the marginalized in general. Listening to young people. Getting beyond GNP, shareholder value, and other outdated metrics of success and failure. Indeed, they even talk about the need for a new social contract.

A bit to my surprise, the world they talk about resetting is not all that different from the one we peacebuilders envision in which rates of violence go dramatically down because we have made huge strides in solving the problems that gave rise to conflict(s) in the first place.

In other words, we have a pretty good idea of what at least the broad contours of the post-COVID world could look like a year or a decade or a generation from now.

Unlike the people who attend Davos each year, few of us have the kind of clout that could begin making those changes at the national or global level.

However, we can all learn and Wendy Hyman’s lesson instead. That is what my book will focus on.

Cool Initiatives

I don’t have to focus on what the reset itself will be like. I won’t have to. The Davos book may be the first book to do so, but it won’t be the last. Plenty of other authors who have far more street cred than I do on those issues will be making the case that we have pull off the equivalent of a paradigm shift in global affairs.

I’ll contribute to the reset by exploring what average Americans are already doing—and easily could do in the months and years to come—to turn the goals enumerated by the likes of Schwab and Malleret into practice.

As you will see when I discuss the really ugly chart I’m currently using to structure research for my book, I do think that there is a role that the movers and shakers who attend events like the World Economic Form have to play. However, the main pressure for meaningful social change will have to come from the bottom up.

There are already signs that average citizens in the United States and beyond are prepared to endorse the kinds of change that would have seemed like pie-in-the-sky idealism a few short months ago.

If you had told me in January that civil war memorials would be torn down throughout the south, that Black Lives Matter would have the support of two thirds of the American public, that economic inequality would be a hot button issue, or that most of us would support climate change legislation, I probably would have laughed in your face. Now, real hope for lasting change exists on those issues and a whole lot more.

New evidence that we could be on the verge of deep and lasting change pours in every day. To cite but two examples in the last week, Nick Kristoff documents how the Biden camp sees the potential for a New Deal-style package of reforms while David Brooks has speculated about what a calm, centrist, but reforming president could do on his first day in office.

In April, I began to notice that the whole tone of what we could do when (and if) we get the coronavirus pandemic under control was shifting. Europeans, in particular, started using the phase and hashtag #BuildBackBetter. More recently, it has begun appearing on the podium when former Vice President Biden gives speeches during the early phase of the 2020 presidential election campaign.

The term was first use in discussions about recovery from the 2004 tsunami that devastated much of coastal South and Southeast Asia. From the beginning, its advocates wanted to do more than just rebuild what natural disasters destroyed but to build more resilient communities in the process.

The term was first use in discussions about recovery from the 2004 tsunami that devastated much of coastal South and Southeast Asia. From the beginning, its advocates wanted to do more than just rebuild what natural disasters destroyed but to build more resilient communities in the process.

Since then, it has gradually moved from disaster relief to broader discussions about social change and gained new currency in Europe when activists started thinking about how to rebuild our societies after the COVID pandemic is tamed. It is in that sense that Biden is using the term as a catch all for his more far-reaching economic and environmental policy proposals.

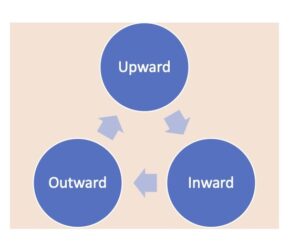

As the Wikipedia page and graphic here both suggest, most such proposals have three parts:

- Reducing the risk that similar catastrophes could occur in the future

- Casting recovery in the broadest possible or “community” terms in which planner set out to address the root causes of all the problems laid bare by the crisis

- Actually and effectively implementing whatever policies emerge

I’ve actually stopped using the term build back better because I think we’re prepared to go even farther. There are movements under way that are both shifting the discussion away from “simply” complaining about what’s wrong toward proposing constructive alternatives that could appeal to a frustrated electorate that is more open to change than it has been in decades.

Let me illustrate that point with just a handful of examples that I know of that could become building blocks for the kind of movement(s) I’ll be describing in the rest of this blog post:

- +Peace is an initiative organized by about twenty global peacebuilding NGOs to create a global movement, initially around peace in our cities.

- The Mary Hoch Center for Reconciliation at George Mason University has a number of projects under way, including one that will help Black Lives Matter and other such activists include peacebuilding in their appeals.

- There are literally hundreds of organizations that are trying to build bridges between left and right. Information on many of them can be found in a searchable map and data base maintained by the Building Bridges initiative at Princeton’s Liechtenstein Institute on Self-Determination.

- Build Up is dramatically expanding its Commons Projrct that uses online discussions to both ease tensions and build grassroots support for racial and gender equality.

- Imperative 21 is a brand new movement that brings together corporate leaders and others who are promoting both a shift toward stakeholder capitalism and business-led initiatives to control climate change. It is so new that it only launched its spiffy new website which lays out its premises and promises during the time I was preparing this post!

- Last summer, I helped lead a workshop of peacebuilding professionals who developed a long list of the kinds of initiatives we wanted to incubate on these and other issues. That was, of course, before the 2020 crises hit, and we are watching our agenda grow in ways we had not thought about a year ago. For instance, one group is exploring ways of creating civics curricula that could help high school and college students become agents for constructive change as we create the reset or whatever you choose to call the post-COVID-19 world.

Put simply, I could spend the rest of my professional career documenting those existing efforts and creating new ones.

Going To Scale

However, if my reading of the Davos book or the trends that led me to stress the interconnected nature of today’s wicked problems in ways that go far beyond the crises of 2020, simply creating those movements and documenting their efforts will not come close to being enough.

By their very nature, the kinds of projects I’ll be writing about (and, hopefully, creating) will focus on specific problems on which we can make measurable project.

If we really want to pull off a paradigm shift that encompasses all or most of the policy areas that matter, we’ll have to learn how to take those efforts to scale in ways that lend themselves both to the widespread adoption of new cultural norms and public policies that are endorsed by the vast majority of the American—and, indeed, global—population.

Over the last few years, I’ve been reading a lot about innovation in the corporate world in which entrepreneurs obsess about taking their ideas to scale. When I tried to apply that notion to peacebuilding and the other issues I am interested in, I realized that taking ideas to scale actually operates in three distinct but overlapping ways that also have to be at the heart of both my book and my grassroots organizing efforts.

Over the last few years, I’ve been reading a lot about innovation in the corporate world in which entrepreneurs obsess about taking their ideas to scale. When I tried to apply that notion to peacebuilding and the other issues I am interested in, I realized that taking ideas to scale actually operates in three distinct but overlapping ways that also have to be at the heart of both my book and my grassroots organizing efforts.

- Scaling Upward. This is what most of us have in mind when we think of taking something to scale. In this case, we worry about how we can reshape public policy or, as my friend Julia Roig likes to put it, get our seat at the grown-ups’ table. We obviously have to do that in order to win, but if I’ve learned anything from half a century as an activist and student of social change, scaling upward can’t really happen to any significant degree if we haven’t gone to scale in the other two ways as well.

- Scaling Outward. The cool initiatives already underway as well as the ones I envision being started are all limited. Most take place in one or at most a handful of communities. Most only deal with a single or at most a handful of issues. In an intersectional and interconnected world of wicked problems, we will have to scale outward in ways that connects movements that are anchored in a single place or on a single issue. Few readers will remember that the civil rights and new left movements of the 1960s did just that. Both started out as motley collections of local initiatives that struggled to come together in the big marches we recall so fondly today and rarely achieved the kind of unity of purpose and message that we tend to read into their legacies today.

- Scaling Inward. Perhaps most important of all, we all have to change, too. When I talk about adopting new cultural norms, I mean that we all need to change, including me. We all need to do a lot of soul searching on what it means to be a peacebuilding agent for radical change, to live with the privilege (in my case as an older, white, male), to see how my major issues fit in with all of the other wicked problems facing the planet, and more. It may be the case that everyone who supports social change does not have to deeply explore his or her personal paradigm. However, if I’ve learned anything over the years, it’s that the new paradigm’s most visible leaders will have to live their values if they expect people to follow them. There is no better example of a movement leader who walked his talk than Representative John Lewis who died while I was drafting this blog post.

Beyond Our Comfort Zones

So the book will document and hopefully incubate efforts toward the larger paradigm shift like goal. But, it will be more than a typical journalistic or academic book that describes or even analyzes events. In addition, I will use it to lay out and keep improving (which is why it may always exist on line rather than in print form) a strategy for turning those dreams into reality.

At this stage, I’ve pulled the existing material into a truly ugly chart that makes a first stab at depicting what I hope to accomplish.

Because I’ll be developing it in future and presumably shorter posts, I’ll just hit the highlights of each of its four levels here.

Because I’ll be developing it in future and presumably shorter posts, I’ll just hit the highlights of each of its four levels here.

- Don’t just focus on peacebuilding. Solve policy problems, too. My colleagues in the peacebuilding community have played a major role in ending some protracted conflicts. However, we are increasingly convinced that we will not be able to dramatically reduce levels of physical and other forms of violence unless and until we make serious progress toward solving the underlying problems that give rise to the conflict in the first place. Perhaps we should give more attention in our own work?

- Change norms as well as policy. In my fifteen years at the Alliance for Peacebuilding, we have built a team that has often gotten us a seat at the table when key public policies are made. We don’t have the impact we could or should have, but I can see progress being made. However, we need to put more effort into changing cultural norms about the ways we deal with conflict and its underlying causes. Recent polls show that such changes are already under way on specific issues. On that front, we actually face two challenges. First how do we sustain and even speed up the rate of change on that front? Second and more importantly, how do we help people see the links between the specific issues and the ways we go about solving problems in this country and beyond?

- Build movements. Before the creation of +Peace, AfP’s policy work primarily concentrated on government leaders. While that work has to continue, everything I know as a social scientist suggests that real and lasting social change has to be anchored at the grass roots. In short, we have to build social movements. We are already seeing some of those kinds of initiatives emerging in physical communities around the country but also in the “locality” that did not exist when I was young—the online world.

- And partnerships. The clouds in the chart reflect the fact that we can’t do this on our own. We will need to find allies and build partnerships with leaders in key sectors, including government, the corporate sector, other civil society organizations, and the media. In fact, if my artistic skills let me add more clouds, I would had ones for the faith community, educators, and more, which you should feel free to add your clouds to my chart.

In closing, let me stress that this is taking me far beyond my comfort zone. I have spent my career writing about comparative politics and international relations which means that this will be first time I focus on American domestic issues. More importantly, I’m not simply an observer who will be writing about what other people are doing. I very definitely have skin in this game and will be working to make the kinds of initiatives I discuss bear fruit.

I will also want the book to take you out of your own comfort zone, too. As my comments on going to scale inward suggest, we will all have to change in some important ways if our endeavors are to succeed. I will want the book to create something akin to what the late pollster and philosopher Daniel Yankelovich called a public dialogue or a “discussion that is so intense that it leaves neither party unchanged.”

Next Time: Two Exponential Curves

Next week’s blog post will look at the interplay between what I hope turn out to be opposing exponential curves—how our growing ability to solve today’s wicked problems will lead to an accelerating decline in the use of physical and other forms of violence.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.Click edit button to change this text.

Also published on Medium.