Civil Society to the Rescue

This is the fifth in an ongoing series of posts about organizations I will be featuring in my forthcoming book, Connecting the Dots. Previous posts covered:

The Political is Personal–And Vice Versa

The next one will explore the Mary Hoch Center for Reconcliation

Two seemingly unrelated things happened last Wednesday that got me thinking in unusually creative ways.

At lunchtime, I was asked by one of the organizations I work with to help it take the next step in its growth. They need to both expand the way their leaders define strategic goals and to raise a bit more money from new sources and in new ways.

Later that afternoon, the White House and the Democrats in Congress reached another roadblock in their negotiations over the Build Back Better and infrastructure bills. I’m still optimistic that something will get enacted and that it will make a difference. Yet, it is clear to me that we cannot expect Washington to take the lead in addressing the problems our country and planet face given the gridlock, mistrust, and everything else we are all too familiar with.

I woke up early the next morning with the realization that I could combine the hopefulness I found in the first with the frustration I feel about the second. This blog post is the result.

I don’t think that what follows breaks a lot of new ground. Still, I’ve come to see far more clearly that the lack of strong, constructive leadership in Washington means that civil society has to come to our rescue.

Put in slightly different words, we will have to rescue ourselves in ways that will revolve around the efforts of the kinds of civil society organizations that I am profiling in the book I’m currently writing and not just the one that just reached out to me.

All of them make four assumptions which I share:

- Massive change is needed in a whole host of areas because we are living through an unprecedented transition in human history

- Given the divisions and everything else that paralyzes national governments these days, the inspiration, catalyst, and momentum that could produce those changes will have to come initially from civil society, especially from organizations like the one that reached out to me

- Meanwhile, rather than focusing on what the current system is doing wrong (which is a lot), it makes more sense to emphasize the constructive steps we can all take to speed us along on what will be long and indirect journey

- Most controversially, we can get “there” by creating and expanding what Margaret Wheatley calls island of sanity and working with the growing number of individuals and organizations who are both wielders of influence among the current powers but who also understand that they need to be part of that transition toward new institutions, norms, and practices

This week’s musings also reinforced two overlapping points I make all the time. There is no “magic wand” we can wave and make our problems go away. Instead, we need to be prepared for a long slog that will take decades to complete.

Transition

When my friends asked me to help them think about their organizational future, I had just finished Azeem Azhar’s The Exponential Age which I’ve reviewed elsewhere. Because I knew my friends were infatuated with Margaret Wheatley’s writing, I next read her Who Do We Choose To Be which I have also written about elsewhere.

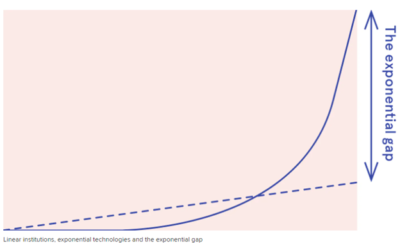

Much of Azhar’s book revolves around a single chart, a version of which I’ve been using since the 1990s in other contexts. As he sees it, much of life is changing at exponential rates, most notably the technologies I wrote this post with and you are using to read it right now. His contribution lies in pointing out that accelerating rates of change are taking place all around us, including in the scientific breakthroughs that made the production COVID-19 vaccines possible within a matter of weeks or the rapid invention and adoption of dramatically cheaper sources of renewable energy. Meanwhile, our ways of dealing with those problems as represented in the dotted line have not changed as much or as quickly. Indeed, my version of the graphic presents it as a horizontal line, suggesting that we haven’t changed our public sector decision making structures much at all over the last thirty to fifty years, at least as far as dealing with today’s global crises is concerned.

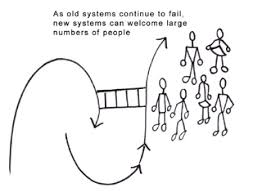

Wheatley goes farther and makes something clear that Azhar only hints at. As she has learned in working with leaders as different as the Joint Chiefs of Staff and networks of American nuns, there are always hopeful signs or bright spots (as Chip and Dan Health call them) in any situation, however dire it may seem at first glance. As Wheatley’s diagram suggests, change makers like my friends have to find ways of identifying what she calls “islands of sanity” in our troubled world, building off their experience, and then taking them to scale so that our (so far) laggard public sector leaders have to respond.

The key to her chart lies in what looks like a rope bridge or sideways ladder connecting the old and new economies. Lots of legacy industries (e.g., anything associated with fossil fuels) are in trouble and fighting with tooth and nail to survive. Meanwhile, new industries are beginning to emerge and struggling to gain a foothold and produce what she calls islands of sanity. What’s neat about this chart and, more importantly, what we’re already beginning to see happen in the real world is that people are setting off on the shaky journey across that bridge. At least a handful of successful leaders in the “old system” are beginning to see the need both to make as quick and painless a transition to the new one as possible and to invest in its success. At the same time as you will see in the rest of this post, some of us who have thought about ourselves as being on the “outside looking in” are exploring ways of joining them by moving across the bridge but starting from its “new system” side.

Islands of Sanity and Bright Spots

As much as I like her work, I would not have chosen the phrase islands of sanity because it can be read as a pejorative statement about those we disagree with who are, presumably, insane. But I like her point because their existence points us in two key directions.

I’ve already alluded to the first of them. Islands of sanity and bright spots already exist, many of which are a lot brighter since the tumultuous events of 2020 shook us up so much no matter what is happening in Washington.

Let me limit myself to climate issues here in illustrating what I mean.

Network news programs talk more about racial equality and climate change. Investment funds are channeling as much as a third of their new stock purchases into climate friendly companies. Cities states around the country are adopting climate friendly policies. Auto companies and other industrial giants are making plans for an all-electric future in which their power comes from renewable sources. Some far-sighted petrochemical companies see the handwriting on the wall and are investing in renewables. Even the Saudi government has announced plans to be carbon-neutral by the middle of the century.

Second and perhaps more important is a subtle shift which we are beginning to see in activist circles which the likes of Wheatley and Azhar at least allude to. We can only go so far in producing social change if we harp on the problems we face, which my colleague George Lopez referred to as the peacebuilding community’s tendency to focus on what he called Gloom and Doom 101.

We need to take our steps across the bridge, too.

Here, social psychologists and others have convincingly shown that while most people do need to learn “the facts” about our problems, they are not likely to make the long-term commitment we need to solve them unless they are convinced that they can make a difference. What social, political, and other applied psychologists call a sense of efficacy really does matter. Or, as I put it in the title of the very first article I wrote on peacebuilding, people need “a rational basis for hope” if we want them to get involved and stay involved for the long haul. And, we know that we need people to be involved for the long haul because we won’t be able to solve any of the pressing problems we face overnight.

Civil Society to the (Gradual) Rescue?

That gets me to the heart of the matter and to a reworked version of this blog post’s overall title.

Those trends are all well and good.

But I do tend to be optimistic, perhaps excessively so.

And even I acknowledge that we are not making enough progress nor are we doing it fast enough.

Still, I’m more convinced than ever that the two qualifiers I added for this section’s title make a lot of sense. It is by no means clear that civil society will come to the rescue. That said, it’s hard to imagine pulling ourselves out of the mess(es) we’re in without a hefty boost from a wide variety of civil society organizations. Hence the question mark. And, as impatient as I am, I also know that if change comes, it will not come quickly, although the argument I’m about to make does suggest that we could easily speed up the pace of change, say, three or four years from now.

To see why I might be right, we have start by clearing up a misconception many of us have about what the term civil society itself means.

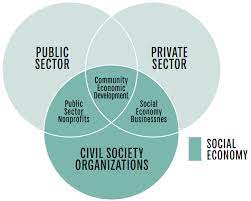

Most of us focus on the kinds of non-profit organizations I work for when we think of civil society. Indeed, there is no question that NGOs, faith-based organizations, charitable foundations, and the like are at its core. However, as this chart suggests, there is more to civil society. It includes at least part of the private sector and even those governmental organizations that include things like social well-being at the heart of their mission statements. The universe of those organizations actually extends beyond the three types included in the intersection sets of the Venn diagram in this diagram.

Even if they don’t use her terminology, more and more of them see themselves as pedestrians on that wobbly bridge linking the declining current ways of dealing with our problems and the new, emerging ones which give me so much hope for the future world in which my grandchildren will spend their adult lives.

What Civil Society Can Do

On one level, a host of civil society organizations are doing just that. I’m blown away by the number of constructive experiments that are already underway and already showing promising results. Georgetown TX, whose mayor describes it as the reddest city in the reddest county in America now gets all of its electricity from renewable sources. Economic cooperatives and benefit corporations are popping up all over the place as companies seek a triple bottom line that includes people and planet as well as profit. Women and BIPOC owners have already created hundreds of companies whose success will benefit previously underserved communities. The Kellogg Foundation has funded dozens of truth and racial healing initiatives in cities and towns around the country, some of which are being emulated by cities and other organizations that have benefited from Kellogg’s largesse.

On another level, we still have a long way to go because of a curious paradox, especially for those of us whose first instinct is to think in terms of gloom and doom. The men and women who founded these organizations often find themselves overwhelmed. Not be the daunting nature of the challenges they face, but by the very success that they are having. Leaders like the ones that reached out to me spend almost all of their time nurturing and growing the wonderful organizations they created.

Unfortunately, Santa Claus has yet to give any of them an extra few hours a day that would also let them come up with even more empowering ideas or build even more all-encompassing networks that would bring supporters together across ideological and issue-based lines. Polls suggest that Americans (and others) increasingly are looking for 2020s versions of what I call that rational basis for hope in the 1980s, and it would behoove the organizations that see themselves as organizations that strengthen the bridge in Wheatley’s diagram by investing in the kinds of organizations that are generating those hopeful new ideas and promising new networks.

It won’t be that expensive. If the organization that reached out to me had, say, another million dollars a year for the next five years, it could free up its founders (all of whom are young women) to continue developing powerful new ideas and expand their own network beyond the economic justice issues that they have focused on so far. With that kind of support, they really could make paths like the one Wheatley drew look more like modern suspension bridges that would increasingly bring more and more of today’s elites and more and more of today’s racial justice, environmental, gender, economic equality, and other activists to see that they are all in this together.

That might seem like a lot of money. And it is. I spend most of my time at the Alliance for Peacebuilding. Our annual budget and that of most of our member organizations isn’t much more than $1 million.

However, for many of civil society organizations—and especially the large private sector companies—that see themselves as being on that bridge, million-dollar investments are by no means unheard of.

And, I am talking about investments here, not simply donations. Some of it would take the form of investing in civil society’s capacity itself whose impact would be demonstrated in non-monetary ways. But most of it would take the form of conventional investment that could and should lead to monetary returns, since many of the new organizations are taking the form of private enterprises, ranging from BIPOC owned real estate networks in American cities to the glitziest new, high tech renewable energy companies.

I had the privilege of being around when some anti-nuclear weapons activists added the idea of win-win conflict resolution to their repertoire in the 1980s which gave rise to the peacebuilding world we know today. We read books like Roger Fisher and William Ury’s Getting to Yes which focused primarily on those kinds of outcomes in corporate or even interpersonal terms and realized that we could apply them to the superpower arms race that was then heating up and to the other global conflicts we focused on after the Cold War ended.

Now, we have the opportunity to take that line of reasoning one step farther and forge a new social contract based on the reality that we really are all in this together and that Wheatley’s bridge and closing Azhar’s gap involves a lot more than just the way we solve conflict.

It involves reconsidering all of the collective decisions we make so that we take one of the lessons we should have learned already in the 2020s seriously—we’re all in this together. We will never get all the way there. However, the strategies that I’ve laid out here could get us closer to those goals and do so faster. And it is certainly worth investing our time and money to see that it happens.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.

Also published on Medium.