Design for the Future

Last week, I wrote the first of what will be four blog posts on an intriguing new coalition of business leaders, Imperative 21. In it, I laid out its basic goals and implied that they were filled with implications for peacebuilders like myself. I also briefly discussed the three imperatives it plans to focus on in the years to come.

Since then, it has launched its public campaign and explored the three clusters of actions it endorses in a bit more detail. In the next three posts, I’ll dig more deeply into each of the three imperatives and their subcategories from a peacebuilder’s perspective drawing on other projects that I’m working on or simply know about.

Before launching into the first of the imperatives, it is worth your time to watch the gripping video the team made to accompany the launch of this campaign.

The first imperative draws out attention to the long-term impact of our actions. Early in my peacebuilding career, we often used a meme attributed to Chief Seattle that we had to think about how what we do today ripples out for the next seven generations. Forty years later when we have to deal with climate change, the generational impact of economic inequality, centuries of systemic realism, and more, focusing on the long term is even more important that it was in the days when the term globalization hadn’t really been invented.

As I suggested last time, design is one of the “hottest” terms in the business world today in part because of the role design specialists have played in developing products as different as the iPhone to Dyson vacuum cleaners to Pixar movies.

Here, however, it’s important to add a key modifier—human-centered—to design, because planning for the next economy or the next peace process revolves around designing for the good of all people rather than dreaming up flashy new objects, however cool they might happen to be.

The term future matters, too. We can no longer afford to think only about the immediate impact of our actions. If we have learned anything from the crises of the last few decades (or the last few months), it’s that the impact of our actions today will be felt decades from now.

As is the case with all three of the imperatives, the I 21 team has broken this one down into three categories which I explore below. Note, however, that I’ve presented them in a different order that reflects the priorities we peacebuilders bring to the intellectual table.

The Imperative 21 Series

This is the second of a four part series on Imperative 21 and its campaign to reset the economy. You can go to the first one by clicking on the toggle switch below. I will activate the other toggles when I write those posts over the next two weeks.

Invest in Social Justice

Accountable to Everyone

Balanced Relationships

The importance of human centered design can be seen in this first category.

The Imperative 21 team define balanced relationships in terms of the public and private sectors. Given their audience, that makes perfect sense since it is clear that the business community would be well served to see the value of the government’s role in providing public goods like a clean environment, education, and public health as we are seeing all too clearly during the current pandemic.

We in the peacebuilding world go even farther when we talk about putting what some of us call right relationships at the heart of all of our work. In other words, it’s not just the public and private sector. We need to find the right balance in all social relationships, at the micro as well as the macro level in ways that extend far beyond the economy

A friend once asked me what a peaceful world would look like. My quick, flip answer was a “world that works for everyone.” For me, that simply means that each element in a system is in sync and the feedback loops lead to overall systems growth, because the people in it have found ways of solving whatever ongoing problems they face. Disagreements will arise, but will not be particularly problematic because everyone will have practical experience in conflict resolution and other forms of problem solving.

In Imperative 21’s terms, two things will have happened. First, we will find a way of striking a balance between the public and private sector in which, in particular, the government steps in to handle the problems that the private sector has trouble with, including those mentioned above. Second and more importantly, everyone puts the good of the whole system ahead of their own self-interest at least in the medium to long term.

Critical in all this is the way we deal with the people we disagree with, which, of course, is one of the skill sets we peacebuilders add to any movement for social change. In recent years, however, we’ve come to the realization that building balanced relationships involves more than just negotiating agreements.

That’s something my friend Chad Ford hss done a particularly good job discussing in his new book, Dangerous Love, In his terms, it makes little sense to only protest against injustice as long as we assume that the other person is “wrong” and we wait for him or her to take the first step in solving the problem. Instead, he thinks it makes more sense for us to reach out to the “other” and invite our adversaries into a discussion about what to do next. The other side may not respond. However, if we compel them to go along, all we are likely to do is to add to the pool of resentment that already exists and drive us farther apart.

That’s something my friend Chad Ford hss done a particularly good job discussing in his new book, Dangerous Love, In his terms, it makes little sense to only protest against injustice as long as we assume that the other person is “wrong” and we wait for him or her to take the first step in solving the problem. Instead, he thinks it makes more sense for us to reach out to the “other” and invite our adversaries into a discussion about what to do next. The other side may not respond. However, if we compel them to go along, all we are likely to do is to add to the pool of resentment that already exists and drive us farther apart.

As anyone has dealt with a person on the other side of the ideological divide can attest, Ford’s “turning toward” is never easy and always takes a lot of time. However, it is one of the few ways we know of forming and sustaining right relationships.

As the work we are doing at the Mary Hoch Center for Reconciliation suggests, true, sustained peacebuilding requires both solving the substantive problems and healing the emotional wounds that divide a given community. That includes finding the balance in all the relationships that Imperative 21 worries about–and then some.

Ensure Equal Access

Because they focus primarily on the business community, the Imperative 21 team defines this second sub-category in terms of access to free and fair markets. This is almost a no-brainer for anyone who has been paying attention to the difficulties people of color have in starting their own businesses.

As peacebuilders, we would go farther here than most people whose primary emphasis is the business community. As the Institute for Economics and Peace suggests in developing its positive peace index, we need to take the idea of balanced relationships farther and build institutions that work, too.

Here, I’ve always found the ideas of the late Sir Isaiah Berlin useful. He argued that the neoclassical desire for the “freedom to” do things was desirable, but not enough. In order to actually exercise those freedoms to, we also had to have what he called “freedom from” abuse in all forms. In the United States today, that would mean having the government (or some other authority) guarantee health care, a basic standard of living, a clean environment, and more for everyone.

In my world, no one has done more to identify the overlap between the economy, democracy, and peacebuilding than the Institute for Economics and Peace and its Positive Peace Index. I can imagine a peaceful society that is neither democratic nor capitalistic. Nonetheless, the research done by the Institute suggests that all the “real world” examples have achieved some degree of democratic governance and at least a reasonably open and free economy that has a reasonably egalitarian distribution of resources, especially income and wealth.

Recognize interdependence

This is the most obvious area in peacebuilding and Imperative21’s goals overlap and reflect the fact that we both use systems and complexity theory to anchor our work, although most corporate leaders only do so implicitly. It also suggests just how much work we still have to do. For both of us, interdependence revolves around the fact that what everyone does affects everyone and everything else through complicated feedback loops.

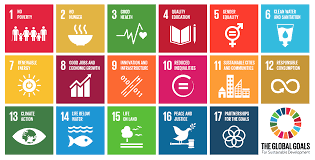

That is easiest to see in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals which the General Assembly adopted in 2015. We peacebuilders like them in part because they explicitly mentioned peace, something the UN had never done in any of its previous statements about social and economic development The SDGs are even more important to Imperative 21 because they reflect that long term balance between all sectors of social, economic, political, and environmental life.

That is easiest to see in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals which the General Assembly adopted in 2015. We peacebuilders like them in part because they explicitly mentioned peace, something the UN had never done in any of its previous statements about social and economic development The SDGs are even more important to Imperative 21 because they reflect that long term balance between all sectors of social, economic, political, and environmental life.

In some ways, this image understates the importance of interdependence which also goes by other names, including intersectionality, wicked problems, or complexity. Whichever term you prefer, they reflect the fact that all seventeen phenomena covered by the SDGs overlap and intersect producing what mathematicians call second, third, and “nth” order effects. That, too, is a convoluted way of saying that it is all but impossible to predict how a system will evolve because interdependency can lead to rapid and unexpected changes which Malcolm Gladwell made famous in his book, The Tipping Point, twenty years ago.

In short, in today’s world, designing for the future means recognizing that it will not unfold in regular or predictable ways. Instead, our plans have to reflect what we’ve learned from systems and complexity theory. We always have to keep our long term goals in mind, but we also have to understand that we will have to take an indirect and constantly changing pathway in order to get there, much like sailboat skippers do when they tack toward their destination in response to changing wind conditions.

Where We Go From Here

I’ve had the privilege of sitting in on some of the meetings in which the Imperative 21 team defined and refined the three imperatives. As should be clear from this blog post, it wasn’t hard to see the overlaps between their work and what we peacebuilders do when it comes to designing for the future. That will be less clear when I turn to investing for justice next week. In the simplest possible terms, we were both taken by surprise—and delighted by—the renewed interest in social, racial, and economic justice that has emerged this year.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.

Also published on Medium.