In my last post. I wrote about the first of two takeaways I drew from Christopher Blattman’s stunningly good, Why We Fight. As was the case then when I wrote about Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), I won’t be focusing on the most important things most readers would take away from his book. Instead, I want to home in on the other new thing—design thinking—that I found in his book from the point of view of someone who has been a professional peacebuilder for longer than Professor Blattman has been alive.

I freely admit to not being an expert on either design thinking or CBT. However, I do know enough to suggest why those of us who don’t have advanced degrees in either mental health or social design should pay attention to them both for reasons that I’ll focus on here with the far newer discipline of design.

Where Design Thinking Comes From

Blattman spends even less time on design thinking than he did on CBT, including it in a final chapter on the practical implications of the years of research that went into the book, some of which seem to have surprised him. To see why he and I think it is important, it helps to take a step back and consider where the term design thinking itself comes from.

People, of course, have been designing things since time immemorial. And until recently the emphasis was on how we go about designing physical objects. Thus, in my youth, I didn’t think about design very often, but when I did it was usually around the creation of physical objects ranging from the shape of everything from this year’s fashion to next year’s automobile models. And, because design was largely the province of architects, artists, and engineers, I didn’t spend much time thinking about it.

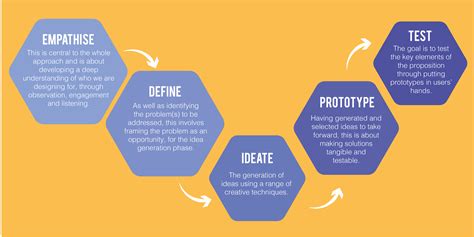

But then in the early 1990s, some design engineers began thinking of their field in much broader terms which led them to begin thinking of design as a tool we could adapt and use in coming up with innovative solutions to complex social problems. Many of them, too, were also IT pioneers which meant, not surprisingly, that early design advocates clustered at universities like Stanford and MIT which had already developed reputations for doing cutting edge applied research that straddled traditional disciplinary lines.

Thanks to Bruce Nussbaum

People in my world who have heard about design thinking probably learned about it as a result of the work of IDEO and Stanford’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design better known as the d.school whose histories are inextricably intertwined. IDEO is legendary for its outside the box ways of designing new products ranging from the mouse to the iPhone to CAT scan machines that don’t scare the crap out of kids who need to spend time in one as part of life-saving treatment. One of IDEO’s key leaders, Dave Kelley, decided to help found (and, I assume) fund the d.school as a place to train the next generation of designers. And, you can probably get the best first glimpse at what the field is like from either reading his delightful book, Creative Confidence, which he wrote with his brother (and Oberlin grad Tom) and includes the delightful story of the CAT scan machine that masquerades as a pirate ship or from the school’s new collection of resources

For the purposes of this post and may own work in general, I find myself (re)turning to Bruce Nussbaum’s Creative Intelligence, which I read when it came out in 2013) and introduced me to the field. I only picked it up because Bruce had been a graduate school friend who studied large scale social change and revolution with the same people I did.

Bruce, however, realized that he was not cut out for the academic world and ended with a distinguished career as a journalist which eventually landed him at The book at Business Week he specialized in innovation. Bruce left when Michael Bloomberg bought the magazine and, ironically, became a professor at Parsons/New School where he taught design thinking for a number of years before spending the bulk of his seventies mentoring startup founders, many of whom wanted to build businesses that would promote social change as well as turn a profit.

Some of the examples in the book are now dated, so it might make sense to consult this video of a talk he gave at a conference in Lisbon shortly after the book came out. You can also click on the picture which will take you to the video as well.

In it, he starts with an idea that many of us who work social change in general and peacebuilding in particular also focus on. We live in what he and I call a VUCA world. It’s a term that was first used by professors at the U.S. Army War College who were trying to figure out what they had to prepare the next generation of American generals to deal with. A VUCA world is:

- Volatile

- Uncertrin

- Complex

- Ambiguous

Ours is a world in which, as Heraclitus put it nearly 2,500 years ago, “change is the only constant.” As Bruce puts it, change cascades on us like water coming over a waterfall.

Under those circumstances, the kinds of incremental strategies in which success comes from major minor tweaks to what you’ve done before just won’t work any more. We need, as his title suggests, creative intelligence, something that is in short supply, as he sees it, in mainstream corporate life. And, I’d argue in political life as well.

Such a world does not lend itself to simple solutions, whether you are trying to defeat the Russians in Ukraine or trying get your company to succeed in a world beset by climate change while you try to address social, racial, and gender inequality.

As I’ve argued in earlier posts, in a complex world, you do need a goal to point toward, what some systems scientists refer to as a North Star. But, there is no simple, linear path that will get you there. To use the language near and dear to design thinkers, you have to iterate or, to us mortals, experiment. Then, on the basis of what you learn from that series of experiments, you keep improving your work and, like a sailboat heading into the wind, you keep tacking toward your goal.

In other words, Bruce draws on versions of design thinking and his own ideas about creative intelligence that privilege social change, long-term commitments, and dealing with wicked problems whose causes and consequences are so inextricably intertwined that you can’t solved them quickly, easily, or separately. A VUCA world, in other words, calls for a combination of design and creative thinking in at least the following five ways that he focuses on that talk.

- Mine for meaning. Dig deeply enough into whatever it is that you are doing so that the people y ou are working with can find something that truly has meaning for them and helps them reach their dreams. Those dreams will vary from person to person and group to group and country to county. But, finding what matters to people, well, really matters.

- Reframing narratives and engagement in ways that define what it is really meaningful in our lives. It is now a commonplace in academic circles to argue that our narratives or the stories we tell ourselves determine how we engage with the world. We can reshape them. That’s what IDEO did when it helped turn a CAT scan machine into what looked like a pirate ship so that kids wouldn’t be scared to death when they entered a scary thing that just might save their lives.

- Serious play. Play has two meanings here. Play can refer to making what we do fun. Play can also refer to a form of experimentation when we play around with things to, for example, come up with the design thinker’s short term goal of a minimum viable product which users can literally play with. It’s when we do this that we have the best chance of connecting the dots and bring unusual things together as Apple and IDEO did when they planned what the first iPhone would be like—a device that could take pictures, surf the Internet, and, lest we forget, make phone calls.

- Make things. Design has always been making things, whether that’s something useful or the ghastly tail fins they put on cars in the 1950s or high fashion that no normal person would ever wear. Seriously, design thinking is about making things, which can be physical like the CAT scanner or a set of ideas like AirBNB’s notion that you could rent out your spare room.

- Take whatever you build to scale. The notion of scaling has gotten something of a bum rap in recent years with the rise of the so-called unicorn companies that develop a net worth of over $1 billion virtually overnight. Still, whatever their flaws, we all want to succeed. We all want to take our ideas and see them adopted by people around the world, whether that’s building the next great app or building a world that has moved beyond war.

And Peacebuilding

As I look back on Blattman’s and Nussbaum’s books, I see the need for each of these five features in peacebuilding and in each of the other fields I’m working in as part of the connecting the dots project.

- Mine for meaning. This is the one area where we have met some of Nussbaum’s challenge with our shift toward locally led peacebuilding. Rather than telling the people we work what they need to do to create a more peaceful community, we ask them to define what a more just, sustainable, and peaceful community would look like and then help them define strategies for getting there. In other words, we are now asking the people we work with to define what they think is meaningful, and we go from there.

- Reframing narratives is also a buzz phrase in my work these days. However, a lot of that work is being done in a top-down kind of way in which we spend time talking with media and other experts. If design thinkers are right, this, too, is best done when we are in tune with the lived experience of the people we work with.

- Serious play matters in both of the senses Bruce has in mind. First, our work is way too serious; working for peace often feels like a burden or what George Lopez called Gloom and Doom 101 in describing our field thirty years ago. If we want to engage people in the work, it has to be enjoyable, whether or not it makes us laugh. Second, our work has to start with playing with ideas and models as suggested in the word tinkering. Rather than coming up with grand solutions, we should tinker with what has worked in one place and adapt it to another. In the language of design thinking, create prototypes that you can test at as little cost as possible. Obviously, there are some limits here. We can’t try any old idea given the fact that lives are often at stake in our work. Still, we can experiment a lot more.

- Make things follows in due course. We can’t just play with ideas in the abstract. We have to make “things” which, in this case, means concrete peacebuilding projects or social movements. We then have to see what works and what doesn’t so that we can keep improving them—our equivalent of the sailor’s tacking back and forth until they get closer to their safe harbor.

- Scaling is, as I’ve argued in earlier posts, the most important bottom line. If we can’t take our ideas and change our selves, our communities, and our country, we will never achieve the paradigm shift I’ve been ranting about Since I was an undergraduate in the 1960s. As far as I know, there is only one book on taking peacebuilding projects to scale, Diana Chigas and Peter Woodrow’s Adding up to Peace and, as is often the case with first books on any topic, it only scratches the surface. It’s still a great book and worth reading, especially since you can download it for free by following the above link.

In sum, design thinking is no panacea, but it is something we should all think about more. I certain am. Thanks again to Chris and Bruce.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.

Also published on Medium.