Leadership

When I started Connecting the Dots, I didn’t plan to write a chapter on leadership. Now that I’m more than half way into the book, I realize that it will need one for the simple reason that “the dots” will need strong leadership if they have any chance of producing the paradigm-shift like change they—and I—envision.

That’s easier said than done because the kinds of leadership we have come to expect just isn’t up to the job. In the literal sense of the term, the way we’ve defined leadership is rapidly becoming obsolete in the sense that it no longer is doing the job for which it was created.

In other words, connecting the dots requires a new kind of leadership because, as I’ve been arguing in recent posts (and will focus on in the book), the times we live in require it. Our world is increasingly defined by the interdependence of the increasingly global networks of which just about all of us are a part of.

As a result, the kind of top-down leadership we’ve relied on for decades or perhaps centuries or perhaps millennia is just not up to that task when it comes to the biggest challenges we face today. Unfortunately, coming up with new forms of leadership that do make sense of our networked age is a gargantuan challenge, one that we have not come close to meeting.

Nonetheless, in the course of writing this book and creating an embryonic connecting the dots community, I realized that many of the people I was meeting were experimenting with new ways of leading. They weren’t the kind of leaders my political scientist self recognized who “ran things” from the “top down.” Instead, they talked about leading in new ways that have little in common with our conventional wisdom about the behavior of senior military officers or elected officials or C-suite executives.

That, in turn, led to an embarrassing number of “duh” face palm moments that my grandchildren love for a simple reason. It took me a long time to reach conclusions that now seemed obvious—at least to me. It’s embarrassing because my interest in new forms of leadership goes all the way back to my sophomore year of college when I first learned about systems thinking in both the natural and social sciences. Then, in the 1980s my friends in the Beyond War movement introduced me to a new approach to management which many of them practiced in the Silicon Valley companies they had founded. I found other examples in the co-op movement and in businesses which were anchored in the counter culture like Tom’s of Maine. I also began reading authors like Tom Peters, Steven Covey, and Peter Senge who equated such thinking with excellence and the like.

In the years since then, what were “fringe” ideas in the 1980s have gradually crept into the mainstream as my . Still, I was a bit surprised when I noticed that the individuals and organizations that I will be including in Connecting the Dots were figuring out how to lead in new ways that were consistent with logic of systems and complexity theory and applying the principles outlined by Peter, Covey, Senge, and others as part of their efforts to profoundly change American society.

And most curiously of all, I realized that I wanted to be that new kind of leader, too.

Leadership and Power Meet Systems and Complexity

To see where I’m heading, consider the words of David Ehrlichman whose work I learned about while I was drafting this post. In what he calls impact networks:

To see where I’m heading, consider the words of David Ehrlichman whose work I learned about while I was drafting this post. In what he calls impact networks:

Leaders become adept at noticing how their efforts are related to others, and as a result it becomes easier to identify opportunities to work together. Network leadership is facilitative, generating connections between others and decentralizing power such that people can organize without a top leader, increasing the quantity and quality of relationships between others. Network leaders nurture a culture of reciprocity. [and] demonstrate great humility, sharing credit and acting in service of the whole. In short, they are stewards of the network and its purpose.

Although I won’t have time to go into each of them in this post, take a second to consider some of the terms he used and think about how different they are from the language we typically use when thinking about leaders and their craft:

- facilitative

- generating connections

- decentralizing power

- relationships

- a culture of reciprocity

- humility

- service to the whole

The Classical Perspective

The Classical Perspective

By contrast, think about how different Ehrlichman’s statement is from the way we traditionally think of leadership and a term we invariably associate with it—power.

From that perspective, leaders have the ability to get the rest of us to follow them. Sometimes, we toe the line because of the power of their personality (e.g., charisma). At others, we follow leaders whom we think of a legitimate because their behavior is in line with cultural norms or result from actions in which we directly or indirectly express our consent (e.g., electoral mandates).

But, more often than not, leaders have to use power, whether they want to or not. In a classic 1957 article which almost all political scientists take for granted, Robert Dahl defined power as:

A’s ability to get B to do what it otherwise wouldn’t do.

The crux of the definition lies in the five final words which I (but not Dahl) put in bold here.

Most of us would rather not pay our taxes or get drafted into the military or obey laws on underage drinking (I only have vague memories of that one).

But we file our tax returns on time, submit to induction when the draft board calls our number, or stay away from alcohol until we’re 21 because we are compelled to do so or fear the consequences if we don’t.

In other words, someone has power over us. The reality and/or the threat of violence, force, or coercion helps convince us to go along.

In other words, someone has power over us. The reality and/or the threat of violence, force, or coercion helps convince us to go along.

Let me be clear here. More often than not, the often veiled and implicit threat rather than the reality of violence, force, or coercion is enough to get Dahl’s job done in a country like the United States. And, as the underage drinking example attests, the law and other sources of power don’t always get “B” to do what it otherwise wouldn’t do.

Nonetheless, that threat is always there.

I’ve even used it myself.

In my days in the classroom, I used to tell (threaten) my students that I would deduct a third of a letter grad for each day they handed in a paper late. Even through I rarely enforced the threat, it sharply reduced the number of late papers I got—at least from first time students who hadn’t learned yet that my bark was worse than my bite!

Power With—Not Power Over

Robert Dahl was no fool.

Quite the opposite. Dahl was a lovely man as well as a highly influential scholar. I’m part of a generation of political scientists who delilghtfully grew up in his shadow. One of his books, Who Governs, sparked my desire to become an academic because it was about New Haven which was only about thirty miles from my home town. Similarly, his research on what European political parties did when they were in and out of power helped shape my interest in comparative politics which dominated the first half of my professional career.

Nonetheless, it is hard to escape the evidence that this kind of power and the top-down leadership that it is associated with is running out of steam. Its most naked form—war—almost never leads to a clear-cut winner and the definitive resolution of the conflict that gave rise to the conflict in the first place, as we have seen time and time again since the end of World War II and most recently in Afghanistan and Ukraine.

It’s not just true of war. Leaders are finding it harder and harder to get people to comply in areas of life as different as politics to the workplace and our schools. There are lots of reasons why that’s the case, but underlying just about all of them are the realities of life in an increasingly interdependent world in which the dynamics stressed in systems theory and complexity science define pretty much everything.

The key implication of this now-not-so-new science is that because everything I do directly or indirectly affects everyone and everything else, my actions “today” are likely to affect me “tomorrow.” I put today and tomorrow in quotes in the preceding sentence because I am using them figuratively to refer to the fact that any short-term action can and does have long-term implications.

In Dahl’s terms, if “A” tries to compel “B” to do something “B” doesn’t want to do, it is likely to foster resentment (or worse). In time, those feeling of dissatisfaction, resentment, and the like accumulate until “B” (or you) search for ways to retaliate against “A” (or me).

In other words, the use of traditional power can and all too often does come back to haunt the side that appears to have it, whether that side is called “A” or “me” or “the government.” Now that “what goes around comes around” has become far more than just a cliché, any other kinds of leadership tends to be counterproductive once we cast our gaze past the immediate impact of our actions because the use of Dahl-style power tends to breed resentment, lay the groundwork for future rounds of conflict, and everything (negative) in between.

That brings us back to the kind of power and leadership that David Ehrlichman and many of the young dots I’m trying to connect use that could best be seen as something “A” uses to empower “B” rather than “A” uses over “B.” Romance language speakers have a sense of where this new way of thinking about power takes us. In French, for example, the verb pouvoir simply means to have the power to do something. Je peux faire queleque chose. I can compel you to do something. But just as easily, I can empower you to do something by using the kinds of tools Ehrlichman included in the bullet points I drew from his statement. From that perspective, it makes far more sense to exert power with another person or organization and, in other words, to empower each other.

No one understands this better than Rotary International. I had long been aware of its involvement in peace-related issues, but only became personally involved when I saw that Rotary could be a key partner in connecting the dots—even though most of its members are far older than the organizations I had originally planned to feature in the book. For the purposes of this post, I began paying attention to four key principles that guide Rotary’s involvement in any projects that its officials put in their sig files and raise at every meeting I’ve attended that also provide a capsule summary of what new leadership in a networked world could and should be like (capitals in original):

- Is it the TRUTH?

- Is it FAIR to all concerned?

- Will it build GOODWILL and BETTER FRIENDSHIPS?

- Will it be BENEFICIAL to all concerned?

It by no means includes everything the new kind of leader has to ask. In fact, I’ll be trying to refine the relevant list of skills and tools as I do more research. Still, these four points which I derived from his statement are a good place to start because if you even think about them for a few minutes, you’ll realize that they lead us in very different directions from models of leadership based on definitions like Dahl’s and are more in keeping with Ehrlichman’s.

Promoting the good of the whole. All of the new leaders I’m working with start with this goal. Don’t get me wrong. They all want their own organizations to thrive and their own careers to take off. At the same time, they also understand that their own success depends on what happens to others.

That is the logic that underlies their attempts to deal with the intersectionality or wicked problems of our times in two respects. First is the fact that they understand that we all have to deal with racism, climate change, economic inequality, violent extremism, and the like more or less simultaneously. Second and even more importantly, they understand that everyone will eventually have to benefit from whatever innovations we make if we have any hope of breaking out of the cycle of growing resentment, anger, and violence that characterizes life in the 2020s.

This first goal takes the logic of win/win conflict resolution which is near and dear to the heart of all peacebuilders to a new level. Rather than “simply” trying to resolve conflict, the goal is to transform it by addressing its many toot causes in way that just about all of us are happy with, at least over time.

Building relationships. In the book, I’ll talk about the importance of taking the projects the dots are doing to scale, so I have no desire to underplay that critical goal here. However, as I’ve argued in recent posts on personal growth in connecting the dots, the activists I’m working with all stress the role relationship building plays in their work.

That isn’t limited to just some of the people we are connected to—say our friends or co-workers, although they are clearly critical in this respect. Many of the business leaders whose works I’ve read stress that we should learn how to maintain good relations even with our competitors, since you could well find yourself working working with them in the not so distant future. Leaders of startups reach out to their first customers for feedback as happened to me when I recently signed up as an early adopter of www.twosapp.com which seems ideally suited to someone like me—a disorganized activist and author who is spread entirely too thin.

In those relationships, we stress many of the themes Ehrlichman mentioned, including actively facilitating relationships among people who could and should benefit from getting to know each other, building connections within your network, and fostering reciprocal relationships in which all participants benefit.

Decentralizing Power. This term does not appear, per se, in Ehrlichman’s list, but it certainly is implicit in his statement. Dahl’s definition of power lends itself to top-down leadership and analysts often point to the military as an exemplar of its use. Now, however, even militaries are seeing the benefits of decentralizing power. When they don’t, they can suffer the kinds of setbacks the Russians are currently suffering in Ukraine where all accounts suggest that they are trying to manage the battlefield from Moscow and giving little leeway to the soldiers in the field.

The fact of the matter is that networks lend themselves to decentralized leaders. To that end, we often heard about strategic corporals during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. On the corporate front, new attention is being given to small, autonomous work teams that come together as need be. For instance, lots of attention is being given to companies like W. R. Grace that does not allow any work group to surpass 150 employees.

In my own field, more and more attention is being paid to local peacebuilding on the assumption that local activists will have a better sense of what might work in their community than we outsiders ever could. Similarly, some of the most promising initiatives in anti-racist work is coming from local communities like Portland Oregon that have had to develop their own solutions to the unique ways of dealing with the problem. Along those same lines, the Kellogg Foundation has been funding and experimenting with locally driven racial healing and transformation initiatives in dozens of cities and college campuses around the country.

Humility. This final term may be the most surprising and also the hardest to pull off for reasons that will become clear in the final section of this post. Leaders tend to be ambitious and often have out-sized personalities. That’s as true of the leaders I will be focusing on in the book as well as the often narcissistic men and women who make the headlines today.

But what Ehrlichman put his finger on is the need to subordinate their personal goals to what he called the good of the whole. That can take many forms, ranging from a phrase I use a lot—knowing how to “leave your ego at the door”—to understanding that growing your organization as quickly as possible (the clichéd 10X ROI) can actually be counterproductive.

New Leadership in Practice

Because I only decided to write a chapter on leadership a few days before I wrote this post, I haven’t made final decisions about which organizations to use as examples to illustrate either how this kind of leadership is already being used and how it could become the norm.

For now, I’m planning to focus on three very different organizations whose work highlights at least some of them.

Rotary. To be honest, I did not think of Rotary and social change together for most of my adult life. I (mistakenly) saw it as a network of local business leaders who met and networked together. Over the course of the first two decades of this century, I kept running into Rotarians because of their role as peacebuilders and, then, their commitment to social change. As they put it on their web site, “Rotary is a global network of 1.4 million neighbors, friends, leaders, and problem-solvers who see a world where people unite and take action to create lasting change – across the globe, in our communities, and in ourselves” and do so not just on questions of peace, but on health care, the environment, economic development, families, and more.

Rotary. To be honest, I did not think of Rotary and social change together for most of my adult life. I (mistakenly) saw it as a network of local business leaders who met and networked together. Over the course of the first two decades of this century, I kept running into Rotarians because of their role as peacebuilders and, then, their commitment to social change. As they put it on their web site, “Rotary is a global network of 1.4 million neighbors, friends, leaders, and problem-solvers who see a world where people unite and take action to create lasting change – across the globe, in our communities, and in ourselves” and do so not just on questions of peace, but on health care, the environment, economic development, families, and more.

Rotary is relevant here because its clubs all adhere to the values listed earlier but do in a highly decentralized manner. Most of us think of the local clubs that meet weekly and engage in community development projects, but there’s a lot more. Gretchen and I belong it to its virtual “E Club of World Peace” whose weekly meetings take place on Zoom and whose projects span the globe. We also regularly attend the meetings of an adhoc club that is spearheading racial healing work in Oregon.

No one tells the local clubs what to do—at least as long as they support those four goals. And, they all work in different ways which I haven’t been able to synthesize—at least not yet.

Still, one ritual practiced by the E Club of World Peace tells me a lot. As people electronically file into to each weekly session, Rudy Westervelt who helped found the club, personally greets everyone and says something or asks a question in ways that make individuals who may never physically meet each other face-to-face feel at home.

If that’s not Relationship Building 101 in the digital age, I don’t know what is….

Lead for America. Lead for America is one of many organizations that is trying to address toxic polarization and the related leadership gap plaguing the United States. Although it operates in all fifty states, it focuses on underserved communities, especially in rural areas in the so-called fly-over states. In its signature program, young people spend a year or two as paid AmeriCorps volunteers who work with an established organization in such a community, preferably one that they are originally from. So far, they have served in more than 200 communities and, of the volunteers, over 90 percent have remained in that community to continue their work after the fellowship ends.

Lead for America. Lead for America is one of many organizations that is trying to address toxic polarization and the related leadership gap plaguing the United States. Although it operates in all fifty states, it focuses on underserved communities, especially in rural areas in the so-called fly-over states. In its signature program, young people spend a year or two as paid AmeriCorps volunteers who work with an established organization in such a community, preferably one that they are originally from. So far, they have served in more than 200 communities and, of the volunteers, over 90 percent have remained in that community to continue their work after the fellowship ends.

Lead for America is growing like gangbusters in part because there are millions of young people who don’t want to move away from their home communities. Instead, they want to stay, for example, in a community like Duluth (where one of my friends is currently Lead for America fellow) and do their part by turning the organization’s goals into tangible projects that they can contribute to

Born into every American community are the talents and skills it needs to address its most critical challenges. But for far too many young people across the country, success has been defined as leaving home and never coming back.

Zebras Unite. I wrote a post about Zebras Unite in the fall. Since you can read it or check out their own web site, I won’t repeat that here. Let me focus, instead, on the way they deal with leading their dazzle (yes, zebras in the wild gather in dazzles).

Zebras Unite. I wrote a post about Zebras Unite in the fall. Since you can read it or check out their own web site, I won’t repeat that here. Let me focus, instead, on the way they deal with leading their dazzle (yes, zebras in the wild gather in dazzles).

Once the movement grew beyond the four founding doulas (yes, the zebras do not take themselves too seriously—just their work), they realized that they had to structure their movement in a way that was consistent with their values, which are also the ones I’ve been discussing here. To begin with, they created formal organizations that both met legal requirements yet were consistent with those values, most notably establishing their main outward facing business as a coop.

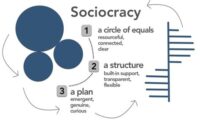

More importantly for our purposes here, they decided to adopt sociocracy to govern itself. While sociocracy can get very complicated, everything about it revolves around a point made on the Sociocracy for All web site—

We believe the best decisions are made when everyone’s voice is heard, that’s why we use sociocracy to save time, make inclusive decisions and create more human organizations.

To make certain that every voice is heard, the Zebras Unite coop is made up of dozens of self-governing “circles” that are organized around both local chapters around the world and on specific themes. Thus, I’m part of one that is developing ways of getting Zebra-like ideas included in curricula at all levels, ranging from high-end MBA programs to the way economics is taught in America’s public school system. Each circle is represented in larger circles that have responsibility for managing the Zebras’ enterprises writ large.

To make certain that every voice is heard, the Zebras Unite coop is made up of dozens of self-governing “circles” that are organized around both local chapters around the world and on specific themes. Thus, I’m part of one that is developing ways of getting Zebra-like ideas included in curricula at all levels, ranging from high-end MBA programs to the way economics is taught in America’s public school system. Each circle is represented in larger circles that have responsibility for managing the Zebras’ enterprises writ large.

So far, it is not clear that sociocracy saves tie, although it has helped the dazzles be more inclusive and humane. The hope is that, in time, having relationship building become as important as carrying out the specific tasks will make it easier for the Zebras to work among themselves and change the way everyone they come into contact with goes about their lives.

Isn’t There Always a But?

As is almost always the case during times of sweeping social change, there is one huge caveat to this story. As wonderful and inspiring as these new leaders are, they still have to operate in a world in which Dahl’s definition of power and tradition perspectives on top down leadership still prevail.

In other words, there is a “but.”

I’m writing my book and catalyzing the related Connecting the Dots Community because I’ve been blown away by the progress that organizations like these three have made—and not just on the leadership front.

That doesn’t mean that we can escape the fact that the existing paradigms that still stress top-down leadership remain the norm. The momentum may be swinging in the other direction that could lead to effective responses to climate change, programs that reduce systematic racism, and promote greater economic equality by promoting leadership along these lines.

Nonetheless, organizations like these three are swimming against powerful institutional and cultural tides. Especially as they get bigger and their impact grows, they often find themselves pulled in opposing directions by what former Harvard Business School professor John Kotter calls two competing operating systems.

In their different ways, the leaders of the three organizations mentioned here understand that, whether they have read Kotter’s work or not. They understand that the real world is filled with pressures to grow at any cost and to therefore lead from the top down. They face stiff headwinds on any number of fronts, including limited funding to their own difficulties in finding the energy to work across issue-based and ideological line.

So far, they have been able to prosper while resisting the pressures to “play the game” according to the established rules. Let’s hope that they continue to grow fast enough to enable us to avoid the kinds of catastrophic outcomes that are staring us in the face on so many fronts.

I’m not sure that they will succeed. However, I’m going to give these and the other “dots” I’ll be covering in the book all of the help that I can.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.

Also published on Medium.