I have to thank my (very) old friend Les Leopold for pulling me out of a writing funk.

I Haven’t written a blog post in a few weeks. To make matters worse, I haven’t been making as much progress as I’d like on my book on US domestic peacebuilding and paradigm shifts.

Then, even though I had another meeting immediately thereafter, I decided to go hear Les talk about his book, Wall Street’s War on Workers to the DC area Oberlin alumni club.

I’m glad I did.

Not only did it pull me out of my authorial funk, but it pointed me (and maybe him and maybe the people I work with) toward ways of dealing with divisions—and worse—that may come with the second Trump Administration which will begin a few hours after I post these words.

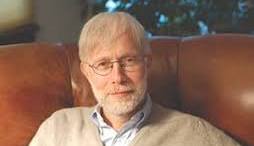

Who Les Leopold Is

Les founded the Labor Institute in 1976 and still serves as its Executive Director almost half a century later.

The Institute is not affiliated with any wing of the trade union movement but works with all of them on a variety of educational and movement building activities. These days, it focuses on providing training and related services that connect union members with broader issues in their communities, including the environment, immigration, and workplace safety and health.

In recent years, Les has also become a prolific author with a penchant for witty titles for books that dig into some of the most complex “wicked” problems facing not just the union movement, but our country as a whole.

That started with a book on his mentor, Tony Mazocchi—The Man Who Hated Work and Loved Labor. He went on to The Looting of America, How to Make a Million Dollars and Hour, and Runaway Inflation.

That led to his most recent book which I had the privilege of reading in draft form and then helped him pitch it to my publisher. That didn’t work out, and Les ended back with his longtime partners at Chelsea Green which was a better match for him to begin with.

I’ll come back to his book and argument in a moment.

Our Political Friendship

Les and I go back to the fall of 1965 when we were both awkward first year students at Oberlin, equally convinced (though we never talked about it at the time) that we were hopelessly unprepared to cope with our more precocious and (seemingly) more socially, intellectually, and politically mature classmates.

My first clear memory was of our dropping our dates off at May Cottage at 10:59 one Saturday night (believe it or not, first year women students had to be back in their dorms by 11:00 on weekends). He suggested that we go next door to Professor Carey McWilliams’ house where some students were visiting. Including women out after curfew. Including the junior resident who supposedly enforced the rules at May Cottage. And my first serious run in with alcohol when Carey poured me a milk shake sized glass (as I remember it) of bourbon.

His first clear memory of me came a year later when I apparently taught him about chi-square which got him interested in doing serious research. As someone who went on to focus on statistical research early in my career, I’m mortified that I ever taught anyone about chi-square which has to be one of the least useful statistical tools in the political science arsenal. End of useless social science rant.

We spent our four years at Oberlin organizing the anti-war movement, taking classes together, and enjoying the fact that we were both interested in more than just Vietnam and student politics.

After graduation, we didn’t see much of each other over the years, although close mutual friends kept us up to date on each other’s lives.

Then, as we began planning our fiftieth reunion, Les reappeared for one unlikely reason. His son was still studying at Oberlin and helping plan the reunion gave him excuses to go visit Chester.

Oberlin reunions are unusual. Instead of golf tournaments or fund raising booster events, we spend a lot of time talking about the political issues that turned us into activists in the 1960s and kept some of us in the “business” half a century later. That was particularly true for our class since at least twenty of us had built entire careers with roots in our sixties activism.

We realized then that our lives had taken us in different directions. Les had become a union guy; I was a peace guy.

But because we both always had the broader interests I alluded to earlier, we got to talking. And organizing discussions at the reunion itself.

And kept talking. Renewing our friendship. Remembering how much we enjoyed each other—including discussing bad statistical tools.

Wall Street’s War on Workers

That reunion was in 2019.

Donald Trump was president. He had won for all sorts of reasons, one of which was the ongoing drift of white working class voters to the right that had begun when we were in college. Although he hadn’t been there that weekend, I had been in Oberlin for a conference on democracy at which J. D. Vance spoke about his new book, Hillbilly Elegy, which I liked a lot (and still do, despite Vance’s own political shift rightward). It was clear that most of the Oberlin lefties of all generations had no clue about what Vance had written about. It was as if we lived in two different countries.

Les had already decided that he had to figure this out because he saw it first hand. Many of the white union members he worked had indeed voted for Trump in 2016 and would do so again twice more. At the same time, they didn’t live up to the stereotypes of the bigoted, ill-educated, intolerant, and angry older man first popularized in the Archie Bunker’s character in All in the Family or pilloried (at what turned out to be her expense) by Hillary Clinton in her 2016 reference to the “deplorables.”

Les decided to do his research that led to his book which was published just about a year ago, thank goodness without a single chi-square. Here’s a talk on the book as a whole which is well worth the hour it would take to watch it.

Among other things, Les found that most of the working class voters who had supported Trump and other conservative candidates still held progressive views on most economic issues. They weren’t all that right wing even on questions like race.

A (perhaps the) bottom line is that they felt ignored and even dissed by a Democratic party that seemed to prioritize other issues. In our discussion last week, he talked about the fact that the Democratic platform spent a lot more time talking about transgender issues than it did about social class.

While Les and I both support the Democrats’ positions on gender, race, climate, and other issues of the day, it does seem as if they are paying the price for shunning what had been their most loyal base of support.

Where We Go From Here—Rotary and the Working Class?

So, I asked Les about his plans for doing something about the dilemma we find ourselves in as Trump prepared for his second inauguration.

Obviously, we couldn’t get very far since mine was the last topic he was asked about in the Q and A part of his talk.

Nonetheless, he made it clear that he is interested in starting a movement that starts by listening to workers—their worries, frustrations, and hopes. It might include some union leaders but would have to be independent of them so that it could come up with new, creative alternatives to the status quo.

Meanwhile, my wing of the peacebuilding community is beginning to talk about something similar in what we at the Alliance for Peacebuilding are calling Peacebuilding Starts at Home. The word ”home,” in our case, means the United States but also literally at home—how we deal with the conflicts in the microcosms of our daily lives.

Our gut instinct is that whatever we build will have to seek new partners and allies, too. The traditional peace movement (including AfP where I do almost all of my work) has to pivot and figure out how to work with people who were not in our universe before, including activists who focus on race, gender, climate, class, and more.

So, I told Les two things that evening.

First, although I would have loved to stay on the Zoom and keep our discussion going, I had to switch to my Rotary Club’s meeting at which how Rotarians deal with social change was the evening’s topic. Needless to say, the substantive content of the two meetings was quite different.

Rotary is, after all, decidedly middle class. But, my wife and I joined because of its commitment to peace and to service leadership.

So, I kept thinking about if and how the workers’ movement that Les envisions and the Peacebuilding Starts at Home community that we are creating could work together.

Second, I told Les that I’d need a few days to think all of this through which ended up being this blog post.

Aging But Still Active

I reached another lovely conclusion from that discussion.

He and I and a few of our friends from the old days are lucky, We are all in the second half of our seventies. And while most of our friends have retired and some have died, a surprising number of us are still engaged. And in our case, Les and I are still pretty much at the top of our intellectual game.

What a gift to still be able to do the work and to learn and to grow intellectually and politically!

And all that leads to a powerful question that Gretchen and I first posed when we met with Bob Putnam of Bowling Alone fame shortly after we had turned sixty-five and he had hit seventy.

How can we aging boomer maximize our contribution to the greater good now that we were freed from having to make a living in the time we have left?

I’ll post this article a few hours before Trump’s second inauguration.

I’ll probably miss the festivities from the Rotunda because I have a meeting of the New Paradigm Coalition at noon.

But, once the dust settles from the ceremony, one of my next steps will be to set up a Zoom call with Les before I head to the New Pluralists’ workshop at the end of the month. They are probably not where Les would look first for new allies. Nonetheless, getting labor into those discussions would be worth his while and mine.

In short, a lot has changed in the last fifty-five years, including all of our hair color. Nonetheless, friends like Les keep me politically young both because of their enthusiasm and because they force me to question some of the assumptions that shape my political life.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.