Changing Our Narratives

I thought I knew what the Connecting the Dots Community would look like until a couple of conversations last week derailed me.

As you will see below, they convinced me that the gargantuan political task I’d laid out for myself was not gargantuan enough. I had to do more than “just” build grassroots movements. I also had to help them—and, more importantly, the rest of us—redefine the way we thitruly gargantuan problem(s) we face as a country and as a species.

Put simply, we also have to change the stories we tell ourselves literally about ourselves, those problems, and, finally, what we could and should do about them.

A Refresher Course

As regular readers of my blog will know, I will be part of a team that will build a political movement to do just that. But, because I don’t have that many regular readers….

Here’s a brief recap of my earlier posts along these lines.

Over the last few months while I thought I was simply writing a book, I identified a manageable number of organizations that want to work across ideological and issue-based lines to promote sweeping social and political change by working largely within the system. I am including all of them in that book, which, not surprisingly, will be entitled Connecting the Dots. In a Zoom call one day in December, two of my favorite “dots” suggested that I wanted to do more than write about them. I wanted to help them succeed. And that couldn’t be done unless I helped create a space in which I could bring more and more of them together so that they could come up with grass roots based projects that they could do together which I refer to as catalytic convening.

My Oldest and Newest Friends Chime In

Then, I had Zoom meetings last week with literally my oldest and newest friends who convinced me that this kind of work had to have a narrative component as well.

I met Dick O’Neill before we started kindergarten back in the Dark Ages (actually 1952). After not seeing each other for ages, we reconnected after our 35th high school reunion and started working on a bunch of things, one of which led me to the idea of catalytic convening in general and connecting the dots in partic ular. When we talked this week, Dick and a friend suggested that I needed to add to the locally based projects since their expertise and personal networks lay elsewhere and I would need input from people who were not first and foremost grassroots activists.

Then, Devin Thorpe said pretty much the same thing. Unlike Dick, he and I only met in December and hadn’t talked to each other in a while because he and his family were moving from Utah to Florida over the holidays. As I suggested in last week’s post, he was looking forward to picking up our conversations after they got settled so that we could begin planning some next step on top of what we had talked about last month. Since, like Dick, his network does not involve a lot of grass roots activists, he already had me thinking about the ways that my original project could and should be expanded.

Writing the Next Stories (Oops, I Mean Narrative)

Both got me to take a fresh look at a word I’ve resisted using until recently, even though the concept underlying it has been part of my political life since the 1980s.

Perhaps because I was trained as an empirical social scientist, I’ve associated the term narrative with deconstructionist and postmodern thought which made it an easy concept to ignore given my fixations with statistics, mathematical models, and the like. Then, when I discovered complexity science whose overlap with postmodern thought is considerable, my views began to soften.

What’s more, I’ve always thought of myself as a story-teller even more than as a data analyst, going back to my days as a camp counselor which, oddly enough, got me interested in social science teaching in the first place.

Then, a couple of years ago, yet another friend, Helen Kramer, introduced me to Amanda Ripley’s game changing post on complicating the narrative(s) which helped launch her into the research that led to her stunning book, High Conflict

All in all, I’ve come to see that we need to change the stories we tell ourselves (i.e., our narratives) if we hope to take the kinds of movements I’ve been writing about in recent posts to scale. And that can’t be done simply by starting and expanding locally based movements.

My friends have convinced me that we need to simultaneously start a second track that will bring together creative thought leaders whose work does not take them to grass roots initiatives very often but can shape the way we all think in at least three ways.

We’re All in This Together

If I’ve heard this phrase once, I’ve heard it a million times since the pandemic hit two years ago. Not just on COVID, but on all of the issues we face.

If I’ve heard this phrase once, I’ve heard it a million times since the pandemic hit two years ago. Not just on COVID, but on all of the issues we face.

What’s frustrating is that it’s not a new phrase for me. I’ve been stressing its importance since I was involved in the Beyond War movement in the 1980s, arguing that we all have to base as much of our lives as possible around its implications.

We have to make the good of the whole—including our families, our communities, our workplaces, our countries, and our planet—at least as important as our own self interest. We can’t deny our individual goals and needs. However, it has become increasingly clear that we can’t reach one without also reaching the other.

Lots of people have begun at least paying lip service to this notion; some of us have actually done something to make a transition toward “we first” sometimes in surprising ways as the New York Times reminded me on Tuesday with a story about this year’s annual letter from BlackRock CEO Larry Fink about corporate social responsibility.

Unfortunately, the fact of the matter is that few of us have internalized stories like that and made them a central part of our identities and of the values that determine what we do—anywhere and everywhere.

In short, the first step in defining the new narrative(s) will be to come up with the stories that will help people truly see that we are all in this together.

I put the “s” in narratives in the previous sentence in parentheses, but I didn’t really need to. There is no single magic narrative. There will have be lots of them. That’s one of the key lessons I took away from Katharine Hayhoe’s remarkable new book on climate change in which she suggests that the same stories that work for me probably will not work for her neighbors who raise cattle on their ranches in west Texas. To paraphrase one of Walt Whitman’s most famous one lines, because we are multitudes, we will need a multitudes of powerful stories.

Wicked Problems

There will, however, be at least one more common denominator to those stories above and the fact that we are all sailing in the same leaky “boat.”

They all will have to help people see that we have no choice but to tackle a lot of the problems we face simultaneously, however different they may seem at first glance. We have all been brought up to think of the issues we face as separate or distinct. COVID. Racism. Economic inequality. Climate change. Add your favorite.

But in my meetings with Dick and his friend and then later with Devin, we all realized that we had to stress the ways in which the issues we face inherently overlap with each other. Lots of my younger, progressive friends call this intersectionality. Those of us who think in terms of complexity science are more inclined to refer to them as wicked problems whose causes and consequences can’t be solved quickly, easily, or separately—if they can be solved at all.

Seeing that they “can’t be solved quickly, easily, or separately—if they can be solved at all” is at least as important as seeing that we are all in this together.

And alas, most of us are not any closer to internalizing that realization either.

More often than I care to admit, I look for quick fixes especially to COVID which has disrupted our lives for two years. Enough. Many of us still look to our leaders to come up with “silver bullet” that will allow us to do the equivalent of the way I jokingly refer to myself—wanting to change the world by the end of next week. Silly.

We all have to learn the lesson of Walter Mischel’s famous marshmallow test.

In the unlikely case that you haven’t heard of it….

In the unlikely case that you haven’t heard of it….

Fifty years ago, Mischel conducted a famous experiment in which he offered a toddler a treat right away (usually a marshmallow but it also worked with pretzels) but offered two of them if the child would wait fifteen minutes or so. The experimenter left the room and came back after the allotted time was up and gave the kid who could wait another marshmallow or pretzel or whatever treat was on offer that day.

What’s important about the test is that Mischel and his team tracked those children for more than a decade. They discovered that the kids who could defer gratification that one time also developed better study skills, SAT scores, and the like.

Deferred gratification not only helps toddlers get more marshmallows and get into better colleges.

We all need it today as we deal with the wicked problems that face our lives that are even more interconnected and hard to solve than you might think if you “only” look at the issues that have burst out into the open since COVID hit.

Strategic Communication

Finally, Dick and Devin also are important for our work because they have both been involved in strategic communications, in Dick’s case in the government and Devin’s in the private sector.

It’s one thing to come up with the narratives about interdependence or intersectionality. It’s another thing to have people hear them and then decide to act on them.

The first part of my connecting the dots community can do some of that at the local level and in face-to-face communications.

But we also need to get these ideas out into the broader communications ecosystem that people actually turn to for information and ideas.

Once more, you don’t need me to tell you that Amanda Ripley is right. We need to complicate a narrative that focuses on everything from polarization to quick fixes.

That, too, can’t happen overnight, and it can’t happen until we begin getting more and more of these new narratives onto people’s radar screens, whether that is literally onto their phone and television screens or just into their personal space in general.

We have learned a lot about how new ideas get adopted by a population over time. So far, much that knowledge has been applied to divide us further or to make us angrier toard each other or toward our leaders.

The time has come to begin shifting the moment toward more realistic and uplifting stories in ways that go far beyond the world of journalism that Ripley focuses on.

Connecting Part A to Part B

I still have lots of questions here for what will be Part B.

Who to invite? What the agenda should be? Once we come up with new narratives, how do disseminate them and test their impact? And more.

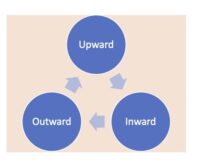

Still, I’m clear that the Connecting the Dots Community will also need this kind of initiative to complement the one I’ve been talking about in recent post (Part A) if we are going to take these efforts to scale in any of the three ways I’ve been ranting about for the last year or so.

- This is the area we think about most when we think about scaling a political movement because “upward” is where new public policies get made. I don’t especially like it, but the fact remains that the path to policy innovation normally passes through simple but powerful narratives hat lend themselves to mobilizing including some that I like (Build Back Better) and many that I can’t stand (Stop the Steal). This new initiative can help on that front, but it will take some time to develop the stories and slogans—assuming, of course, that we can.

- The grassroots initiative can spread through word of mouth and conscious efforts to replicate and/or adapt an initiative in other communities. Such efforts, however, will be constrained by the limited number of people involved, the limited resources they can muster, and, of course, the limited number of hours in a day. As we saw in the global proliferation of protests following the murder of George Floyd, media coverage of those initiatives can spread and, in the language of the day, take them viral.

- I suspect that these narrative-driven initiatives will have the least impact on what I’m convinced me be the most important way we can scale things. It is paradoxical, of course, to talk about scaling inward because that carries with it the implication of something actually getting smaller. One of the things that ties my dot connecters together is the realization that we each also need to change ourselves before we can hope to have the kind of major impact “out there” that these pressing issues call for. In fact, I’ve been blown away by the introspective, centering aspects of all the dot connecters I’ve already brought together for the first phase of the community. As important as it may be, I’m just not convinced that new narratives on their own—especially those brought to us by the media—are all that effective at helping us cast our gaze inward.

There will need to be a combination of grassroots efforts (the “old” idea I’ve been batting around for a month or so) with this “new” one.

It is way too early to figure out where this will end up. I only know that it will be challenging—and fun—to get there.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.

Also published on Medium.