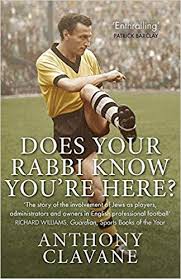

Does Your Rabbi Know Where You Are?

Anthony Clavane’s book has been on my radar screen for a long time. I finally got around to reading it now because I am helping an Oberlin student with her application to get a Watson Fellowship to study the link between soccer, peacebuilding, and social justice. Like me, Julie Schreiber is Jewish, so the joy of working with her also gave me the joy of reading this book. Like all good books about sports–at least for me–Does Your Rabbi Know Where You Are? has as much to say about British politics and society as it does about soccer (oops, I mean football).

The book is about soccer. And Judaism. That starts with its title which might seem a wee bit obscure to American readers. It was a chant often sung by fans of whomever Tottenham Hotspur was playing on a given Saturday afternoon. And, it was loaded with anti-Semitic overtones.

Historically, football fixtures (as they call soccer games) were played on Saturday afternoons at 3:00 PM. That, of course, is in the middle of the Jewish sabbath. Tottenham Hotspurs (or Spurs to us fans) has historically had a lot of Jewish supporters because of its location in North London. Knowing that, opposing fans would jeeringly come out with that question. Or worse, including having “cheers” in the form of hissing noises supposedly reminiscent of Jews being sent to the gas chambers in Nazi concentration camps.

Clavane uses the book to explore the flip side of the ill-intended chant. As he sees it, Jews have been fascinated by soccer ever since they began arriving in significant numbers in London and other major British cities in the late nineteenth century. That holds for Clavane himself who had to be something of a closet fan at his Jewish elementary school (most British elementary schools are religious or parochial in American terms) and often had to sneak out to see games on shabbat.

As far as I know, no one ever chanted does your rabbi know where you are at Ebbets Field or Yankee Stadium on a Saturday afternoon, perhaps because American Jews were never as religious as their British counterparts. Still, as many sports-loving American Jews like myself will remember, we often compiled all Jewish teams for the sports we loved the most. This included extended debates, for example, over whether Rod Carew could be on such a list which did not have a lot of great Jewish second basemen. It turns out that while Carew had been married to a Jewish woman, he had not actually gotten around to converting, so he has normally been struck off those lists.

In the end, Clavane’s book is useful because it charts the changing role of Jews in British sports and, by implication in Jewish society. To be sure, Jews have always had a marginal role in both. However, he does see three critical transitions which should be familiar to any Jewish-American sports fan.

- At first, Jews struggled to make onto teams (sides in British terms) where they faced significant anti-semitism.

- In the post-war years, more and more Jewish players made into the top three divisions of English soccer and did so without making a big deal of their Judaism. Many did not talk about it all.

- Today, there are very few Jewish players, especially in the Premier League. However, Jews did gain ownership and management positions in a number of key teams and helped spearhead the creation of the Premier League in the 1990s which turned top flight English soccer into the multi-billion dollar business it is today. In the last few years, at least one Jew, the Russian-born Roman Abramovich, owns Chelsea and has become one of a number of foreign owners of top level English teams.

Again, anyone who pays attention to the Jewish presence in American sports will not be surprised by these same trends. Despite our lists of great Jewish athletes and the heroics of men like Sandy Koufax who refused to pitch on the High Holidays, the number of Jewish athletes at the highest level has declined as Jews have pursued other pathways to upward mobility. The most recent lists I found for 2018 had eight Jews in Major League Baseball, six in the NFL, and only two in the NBA. By contrast, twenty percent of MLB teams, 33% of NFL teams, and a full 44 percent of NBA teams are owned by Jews.

In the end, this is a wonderful and enjoyable book that should appeal to any sports fan who is interested in the social and political implications of their, well, obsession.

For readers like me whose Yiddish is all but non-existent, the book ends with a glossary….