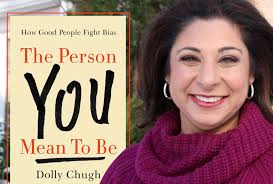

The Person You Mean To Be

Over the last few years, I’ve spent a lot of time reading books by business school professors who wrote for popular audiences and raised issues of interest to peacebuilding and/or comparative politics. Sometimes, the connections weren’t always obvious.

They certainly were in the case of Dolly Chugh, The Person You Mean To Be. In many ways, hers is typical of this kind of book in that she explores personal shortcomings that keep us from reaching our fullest potential. But, perhaps because Chugh is a woman of color, she takes on many of the tough issues that revolve around gender, race, and other identity issues that are at the heart of the two fields I work in.

The book starts off with a personal story she returns to several times. In December 2014, she played dead in a protest organized by Black Lives Matter in the toy gun section of a Toys “R” Us store. As she lies there (and wonders if she will also have time to buy her children’s Christmas presents after the protest is over), she wonders why the United States does not always live up to its ideas. And, as a social psychologist interested in race, she wonders why she does not always live up to her own ideals on this and so many other issues. This book is the result of these and other musings.

Put simply, she writes about the need to move from being what she class believers who care passionately about an idea to becoming what she calls builders who can also create coalitions to build support for those kinds of values. It may seem like a minor distinction. If I only claim that I am not a racist and that you or someone else fall into that camp, I haven’t done enough. In fact, if I am simply a believer in her terms, I put the focus on myself, seek affirmation for my beliefs, may even take a holier than thou attitude, and, last but by no means least, may end up doing nothing constructive to end racism (or any other problem).

Instead, she suggests we act as builders who actually take steps to produce change, ironically, first by looking deep inside ourselves and acknowledge four key personal characteristic that may well keep us from acting, including:

- Shifting from a fixed to a growth mindset. Here, she borrows from Carol Dweck’s pathbreaking research and argues that a growth mindset is critical in dealing with racism, sexism, and the like because it starts with the acknowledgement that I might be wrong and might therefore be part of the problem. Acknowledging that allow us the learn and grow as people in general and on these issues in particular. That is especially important because it allows you to be open to criticism and see why someone might be correct when she or he is angry with you.

- Unconscious or implicit bias. Like Chugh, most of my friends are good liberals who would argue that they are neither racist nor sexist. Nonsense, she (and I would argue). We all have unconsciously held or implicit biases that we get simply from growing up in our country and/or community. She puts a lot of stress on the Implicit Attitudes While I have some qualms about its methodologies, there is little doubt that we all have such biases for reasons that relate to the way we were raised and, perhaps, to the way our species have evolved. She makes it clear that she has them. I know I do. In other words, I accept her premise that these are important issues for us all to work on, whatever our field of work. If nothing else, we have to pay a lot more attention to the tailwinds that made life’s challenges easier for me to deal with as an upper class, white male than they were for people who did not share the privileges of my birth.

- If you are not part of the problem, you cannot be part of the solution. Here, of course, she inverts a key statement from the new left of the 1960s which I’ve used a lot over the years. But note the way she reverses the language. If I don’t acknowledge the ways I contribute to the problem I raise as a believer, I can’t really be an effective builder. In short, she argued for willful self-awareness

- Builders engage. In short, she asks people like me who were born to privilege to ask how we can become part of the solution. As she puts it in the middle of the book, “as builders, we need to make the invisible visible.” We do not have to beat ourselves up or even agree with every demand made in our community or workplace. Rather, we have to become aware of the headwinds that get in the way of women or people of color or the LGBTQ community and actively (and perhaps sometimes quietly) champion their causes by chipping away at the power of those headwinds. In our personal lives as well as our social ones.

Just as important, she shows how these ideas work themselves out in a number of cases from the corporate world, civil society, and her own personal life. As she puts it toward the end of the book:

The more I realized that my willingness to be a work-in-progress would help others to be a work-in-progress, the easier it became.

So, on both a conceptual and an empirical level, this is an important book and worth your time. It is also a lot of fun to read.