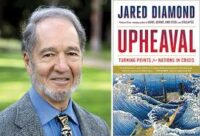

Upheaval

This is both an extremely good but somewhat disappointing book.

Jared Diamond has a richly deserved reputation as an observer of human history and today’s troubled societies. He started as a biologist, became a world class geographer, and now turns to the social sciences in general as he weighs in on the ways societies deal with crises.

The book’s ambition is its greatest strength. He starts with ideas borrowed from his wife’s work as a clinical psychologist who helps patients work their way through personal crises. In so doing, Diamond draws on a dozen insights from crisis psychology and adds a few social ones that help us understand how societies as a whole work their ways through hard ties. That long list can be boiled down to a few of them for the purposes of this brief essay:

- Acknowledging that you are in a crisis

- Honestly accepting personal and social responsibility for it

- Building a mental “fence” around the highest priority items that need solution

- Asking for and getting help

- Personal ego strength and a strong sense of national identity

- Patience

- Dealing with and learning from failure

Diamond illustrates their importance through a comparative analysis of a number of cases in which countries either successfully coped with a crisis or failed to do so:

- Meiji Japan

- Finland’s struggle against the Soviet Union

- Chile before, during, and after the Allende and Pinochet regimes

- Indonesia since independence

- Post-war German reconstruction

- Japan today

- The United States today

This is is where the book’s problems come into play in two ways. First, as one would expect, his coverage of six countries is uneven at best. In fact, there are more mistakes on details than one would expect from an author of his stature who probably could have afforded to hire a fact checker. Second and more importantly, he does not have enough cases to fully separate out the impact of his fifteen or so causal factors and produce anything like a roadmap for dealing with national-level crises.

Diamond could and should be taken to task for the first problem. The second is beyond his control–or that of any other author who takes on a book of this magnitude.

At the same time, this is an important and provocative book whose problems are dwarfed by its ambition, the breadth of Diamond’s coverage, and his engaging prose which routinely and effectively switches back and forth between his own personal experience and what he has learned from his fellow acasemics.

Warts and all, this is a book that every comparativist should read.