Last week, I wrote an introspective post that I entitled Teaching, Learning, Leading, Sponsoring—Draft 1. I wrote it to discipline myself. I was preparing to lead a discussion on Sabina Nawaz’s You’re the Boss for the Next Big Idea Club, and as is my wont, I was reading other things that left me something less than laser-focused on the task at hand.

So, as I often do, I wrote up what I was thinking about to put some closure on that material which then allowed me to refocus on the questions Ania Szczesniewski wanted us to raise with whoever showed up. Writing the post helped me see the key points I wanted the group to discuss but also some of the broader issues I’m dealing with as I get ready to downsize into a condo, the first move I’ve made in more than a quarter century.

I called it Draft 1 because I assumed that the discussion would give me new insights into those issues about learning in general and myself.

I was right about the event which was terrific and thought provoking. I hadn’t taken into account, however, that lots of other things were going on in my life that amplified each of the ideas that came up in that seventy-five minute discussion.

In short, I ended up with a Draft 2 that is very different from the one I had in mind when I posted the first one last Tuesday. I modified two of the four terms I used as categories, but basically the themes are the same, because they all revolve around the remarkable ways I continue to grow even though I’m seventy-seven and most of my contemporaries are slowing down.

So, I also refer to them as things that I am becoming.

Becoming an Elder (Teacher)

As is almost always the case these days, I was the oldest person in the virtual room when the Next Big Idea Club reading group met on Thursday. On one level, that isn’t surprising given my age.

On another, it still felt odd because my self-definition has a hefty dose of having once been the youngest kid in the room. I was one of the youngest (and, I suspect) most immature people in my class from kindergarten on. Somehow, I finished my PhD and got my dream job teaching at Colby almost exactly fifty years ago. As a twenty-seven year old assistant professor (and still pretty immature), I was still the youngest person in the room—other than my students, of course.

The day before our discussion, I had been on a visit to Halcyon House with my friend Shalonda Ingram who lovingly refers to me as an Elder. Given her Native American roots, that is, of course, a compliment, but also a description that doesn’t mesh with having been the youngest kid in the room.

The day before our discussion, I had been on a visit to Halcyon House with my friend Shalonda Ingram who lovingly refers to me as an Elder. Given her Native American roots, that is, of course, a compliment, but also a description that doesn’t mesh with having been the youngest kid in the room.

But it’s one worth embracing. I have been around a long time. I have learned a lot as a political scientist and as a peacebuilder. As a citizen and as an activist. As a teacher and, now, a grandparent.

Shalonda and others expect a lot of elders. Our job isn’t to pontificate and talk about how great things were (or even how different things were) in 1975 when I set foot in my first classroom where I sat on the teacher’s side of the desk for the first time in a class of my own. Our job is to reflect on what we’ve seen and learned in the context of what has changed in all those years.

In short, I can be a useful elder if I also become the other three things on my list.

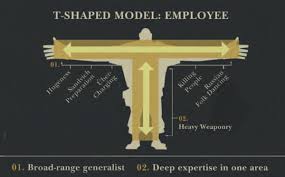

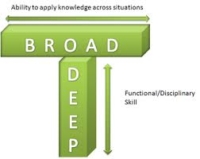

Becoming T-Shaped (Sponsor)

I’m able to be the kind of elder Shalonda wants me to be in part because I’ve enjoyed becoming a t-shaped individual. Actually a double t shaped individual.

Let me explain.

The term was first first invented by the British journalist David Guest in 1991 to describe the kind of person whom he thought would be in high demand I the technological age that was in its earliest stages. A few years later, the term got popularized by the design firm IDEO which is famous for its stable of employees who are adept in their original field but can also apply their expertises across the board as they did when they helped Apple design the original iPhone in the mid 2000s.

I’m extraordinarily lucky in this regard because I have professional training in two fields—political science and peacebuilding. Many of my new acquaintances from other fields are surprised when I tell them how different my two areas of expertise are. In the language I’m using in Peacebuilding Starts at Home, political scientists work all but exclusively in the current paradigm while the most promising peacebuilders are forging a new one.

I published my first book in political science in 1978 and my first peacebuilding article less than a decade later. Although I am not a world class scholar by any stretch of the imagination, I have written and taught a lot in both fields in ways that stretch me beyond my original expertise in French politics or grass roots peacebuilding networks.

More important is the line across the top in the graphic which depicts a t-shaped individual. I started out planning to be a physicist, mathematician, or an engineer and never lost those interests, especially once I started programming computers in my first year calculus class. When I get involved in Beyond War in the 1980s, I developed two new obsessions—with startup culture and personal growth. For the last twenty years, I have been the senior fellow for innovation at the Alliance for Peacebuiding (AfP) where my job is to look for ideas outside of our field that my colleagues could and should try to use in their efforts around the world.

As I pointed out last week, I used to use the term mentor to describe how I use my T-shaped skill set. After having read Rosalind Chow’s book, I think of it more as sponsoring and opening doors for people whose intellectual “camera lens’s aperture” could some day be as open as mine.

As I pointed out last week, I used to use the term mentor to describe how I use my T-shaped skill set. After having read Rosalind Chow’s book, I think of it more as sponsoring and opening doors for people whose intellectual “camera lens’s aperture” could some day be as open as mine.

Becoming a Learner

Over the weekend, my eighth grade grandson asked me how to pronounce Menger sponges (Men-grrr it turns out). As I’m sure will be the case for most readers, my mind went to some kind of device you can use to mop up spilled liquids. It turns out that it has nothing to do with liquids, spilled or otherwise. It’s a mathematical concept, a fractal—there’s one at the start of this essay. Once I discovered that, Kiril put on his “silly grandpa” face.

When I went home, I went down the rabbit hole of learning something about Menger sponges even though there was no obvious way knowing about them could be of any use to me in my work. To see why, just check out the first paragraph of the Wikipedia page:

In mathematics, the Menger sponge (also known as the Menger cube, Menger universal curve, Sierpinski cube, or Sierpinski sponge) is a fractal curve. It is a three-dimensional generalization of the one-dimensional Cantor set and two-dimensional Sierpinski carpet. It was first described by Karl Menger in 1926, in his studies of the concept of topological dimension.

See what I mean?

A lot more than grandparental duty was in play here. The more t-shaped I become, the more curious I am.

A lot more than grandparental duty was in play here. The more t-shaped I become, the more curious I am.

I usually don’t spend a lot of time obsessing about a shape whose surface area gets increasingly large as its volume increasingly shrinks which is why some people find Menger sponges utterly fascinating.

I’m certainly not going to spend a lot of time learning to play Minecraft which, I suspect, is where Kiril learned about them.

Nonetheless, I’m becoming more curious. About the world I live in. About new ideas. About the people we’re going to meet when we move into our new condo in ten days. About what each and every one of us can do to pull the United States out of the run we are in. Especially about things I haven’t thought about yet.

And, I still live by the statement by Marcel Proust which I must have quoted a thousand times in the last forty years, “The real voyage of discovery comes not in seeking new lands but in seeing with new eyes.”

I find myself on my Proustean voyage of discovery to find my next set of new eyes.

Though I’m pretty sure I’ll never tackle Proust’s novels themselves, which I’ve started in both English and French many times, never making it past page 5 in either language.

Becoming a Leader

The final one surprises me the most. It did last week. And it does even more today.

I’ve never wanted to be a leader. I shied away from being a department chair in the days when I was a full time academic. I did everything possible to make certain I would never be asked to be one even though the job rotated. Since then, I’ve never sought leadership roles in the organizations I worked for and with.

In the last days and weeks and months and years, I’ve realized that I’ve been deluding myself.

Like it or not, I’ve been becoming a leader and not just because I’m an elder.

Over the years, I’ve adopted a way of using power through which I enable the people I work with. I’ve come to realize that I didn’t want to be in charge if doing so meant that I would have to exert power over the people I worked with. My learning, t-shaped, sponsoring self developed ways of leading that were consistent with the new set of Proustean eyes that I’ve been teaching and writing about since the 1980s, if not before.

Over the years, I’ve adopted a way of using power through which I enable the people I work with. I’ve come to realize that I didn’t want to be in charge if doing so meant that I would have to exert power over the people I worked with. My learning, t-shaped, sponsoring self developed ways of leading that were consistent with the new set of Proustean eyes that I’ve been teaching and writing about since the 1980s, if not before.

All of a sudden, I’m coming to grips with two facts.

First, I’ve been leading for a long time. As a camp counselor and as part of new left student groups at Oberlin and Michigan in which I was both plenty radical and effective at working with people I disagreed with. Then as a teacher. Now, as a writer, mentor (sponsor), and thought leader. And grandparent.

Over time, I’ve found ways to lead that are consistent with the personal paradigm I’ve been developing over the past half century that also led me to become a t-shaped learner.

Second, I’m also discovering that I like to lead. Not in a top down way. But in developing networks of mostly younger people whose growing skills and impact feed back on my own ability to come up with new ideas and go public with them.

To be sure, I still have no desire to be a department chair or hold any other officially recognized office.

Nonetheless, I’m have one hell of a time working with the like Ania and Shalonda and Kiril and dozens of others people who are now something like the youngest people in the room.

I come away from weeks like the last one—which are also an increasingly common part of my life—both satisfied and eager to keep sponsoring, teaching, leading, and—most of all—learning.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.