The Peacebuilding Pivot

This is the first draft of a paper I’m writing for a workshop on American peacebuilding at Nova Southeastern University which I will be presenting later in the week. It also might serve as the core of a book proposal on the same subject.

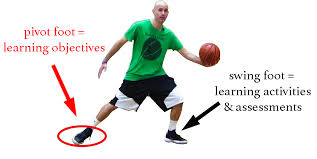

What I will be calling a peacebuilding pivot takes off from my failed career as and continued obsession with NBA big men (and now WNBA a big women). As you will shortly, a peacebuilding pivot has one thing in common with its basketball namesake. We stand firmly on the basis of what we’ve already done but then we set off in a new direction or perhaps directions in the plural given the audience I’ll be talking to.

My background is in global peacebuilding, and my work has always had a political edge. After all, I have spent more than fifty years as an activist and political scientist as well as a peacebuilder.

Most of the attendees at the conference in Florida anchor their work in mediation and alternative dispute resolution. After the first session with them over the weekend, I suspect that their pivot might look a little different from mine, but only on the margins.

On the assumption that I might not be right on that front, I’m even interest than in hearing what you thing. So, feel free to send me comments via email.

Why We Need to Pivot

This rather length post beats home one simple point, albeit one that is filled with wide-ranging implications for how my colleagues and I do our work.

If I’m right, we peacebuilders are going to have to pivot toward a new way of working if we want to achieve the kind of rapid—even exponential—growth we all dream of.

We don’t need to abandon what we are currently doing. After all, we have made huge progress since the modern peacebuilding and conflict resolution communities came together in the 1980s or my student days in the 1960s.

You only need one example to see how far we’ve come. Forty years ago, the term win-win mostly used by obscure mediators who had been trained in conflict resolution which was something next to no one had ever heard of before. Today, it is part of our everyday lexicon that spills out of our mouths and our television screens to describe everything from a trade between two Major League Baseball teams to the sale of a used car.

But that’s not why most of us got into this business. Whether as a student activist in the 1960s or as a young political scientist who discovered peacebuilding twenty years later or a senior citizen forty years after that, I have always had two much bigger goals.

- To help our fellow citizens adopt new cultural norms that prioritize cooperation

- To have a major impact on public policy

If we are going to have even the faintest chance of reaching either of those goals, we will have to pivot. We will have to put less emphasis on building our own field, embed ourselves in existing movements for substantive social, political, economic, and environmental change, and infuse them with the values we have been promoting for the last 40 years.

When I started thinking in terms of a pivot, I thought it was a radical departure and might even get my drummed out of the peacebuilding community. But then as I listened to the young people I work with and wrote about in last week’s post, I realized that we can actually carry out the pivot fairly easily if we:

- rediscover at least one our historical roots Most of us came to conflict resolution and peacebuilding because we wanted to be on the right side of history and saw that this new approach to problem solving could help get us there. To some degree, we lost sight of the first half of the previous sentence as we tried to build our field both in academia and the real world.

- listen to our younger and more demanding colleagues along the lines I talked about in last week’s post and will return to at the end of this one

How to Pivot

I’m not one of those authors who spends hours trying to find exactly the right word that fits whatever it is I’m writing about. “Pivot” is an exception.

I take the word seriously. And I take it literally.

I have this fantasy. I’m six foot nine rather than five foot nine, and I’m still in the NBA. At age 73. Launching my Kareem-Abdul-Jabbar-style sky hook. Of course, it swishes every time. At least in my head.

I have this fantasy. I’m six foot nine rather than five foot nine, and I’m still in the NBA. At age 73. Launching my Kareem-Abdul-Jabbar-style sky hook. Of course, it swishes every time. At least in my head.

Even if you don’t share my basketball fetish, you know that a power forward (like me) pivots by placing one foot firmly on the ground and setting off in a new and dramatically different direction toward the basket.

We peacebuilders need to pivot because our work has reached a plateau. On the one hand, we have made huge progress since the modern peacebuilding and conflict resolution began coming together in the early 1980s. On the other, we are no closer to pulling of the kind of cultural or public policy paradigm shifts I’ve been ranting about since I first read Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions as a college sophomore back in Dark Ages.

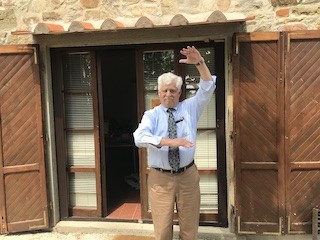

I’ve been making something akin to this case for years, but it came to a head while I was visiting Rondine Cittadella Della Pace in Tuscany in 2019. I had just given a presentation to its students who were spending two years there to hone their conflict resolution and trauma healing skills in which I used this visual metaphor. Alas, we didn’t think to take the pictures that showed just how beautiful that Tuscan village with its thirteenth century castle really is.

My bad choice of backdrop for the photo aside, the gap between my thumb and forefinger in the first one shows how big an impact we had when joined Beyond War in 1983. If you can’t see the space, that’s the point. Next to no one knew anything about peacebuilding or conflict resolution at the time.

My bad choice of backdrop for the photo aside, the gap between my thumb and forefinger in the first one shows how big an impact we had when joined Beyond War in 1983. If you can’t see the space, that’s the point. Next to no one knew anything about peacebuilding or conflict resolution at the time.

The second picture demonstrates where I thought we were in 2019. You could see the gap between my fingers but it was still small enough to make it clear that we still didn’t have a seat at what my friend Julia Roig calls the grown ups’ table We may not have a place near the head of Julia’s grown ups table for most holiday meals. Nonetheless, we at least getting invited to it from time to time. Maybe not for the main course but at least for snacks.

I needed both arms and a larger format for the photo to suggest where we needed to go next which comes with the obvious corollary that we can’t get there only using business as usual. When I got home, I developed those ideas in the last two chapters of my introductory textbook in peace and conflict studies in which I called for the creation of a new kind of political movement in which we joined forces with existing networks that worked for social change and infused them with peacebuilding values. The dizzying array of events since the book came out at the end of 2019 only reinforced that conclusion.

In other words, the peacebuilder’s pivot starts by planting one of our “feet” firmly on the “ground.” I take that to mean that there is no need to stop what we’ve been doing that have led us from the first to the second visuals from my visit to Rondine.

In other words, the peacebuilder’s pivot starts by planting one of our “feet” firmly on the “ground.” I take that to mean that there is no need to stop what we’ve been doing that have led us from the first to the second visuals from my visit to Rondine.

The events of the last few months, however, have convinced me that people are not likely to join our efforts en masse if we appeal to them using peacebuilding and conflict resolution themes alone. As we are seeing every day in the news, they are more likely to be mobilized around the specific issues we face, including race, public health, gender, climate change, gun violence, the election, and more.

They reminded me, too, that average citizens are rarely motivated to act around peacebuilding, conflict resolution, or any such process oriented goal. Instead, it makes sense for us to prioritize the substantive issues that do lead people to act and, as I am about to argue, then add peacebuilding and conflict resolution perspectives.

The themes we have been teaching and writing about and the experience we’ve gained from decades in the field are needed now more than ever. We just need to promote them in a new way, too.

Infuse Them With Peacebuilding Values

I do not think we should even think about creating any movements of our own with the exception of +Peace with which I work and which is aimed at peacebuilding, per. Movements focusing on specific problems already exist. Dozens of local and national movements have come together around racial justice as we saw most recently in the various marches for Black Lives around the country. Some of the most promising ones have not made it onto most of our radar screens during these charged times. Thus, I’m personally intrigued by initiatives in the corporate world, including Imperative 21 and Zebras Unite.

If we combine our efforts with theirs, we could be creating a new kind of win-win outcome that helps them grow and gets us a permanent seat at Julia’s grownups’ table because it is part of a cultural revolution.

We do have a lot to add to these burgeoning movements. My wing of the peacebuilding world has four decades of experience building bridges across ideological and other divides because we can help people become more empathic, avoid using stereotypes, and become more creative in finding potential win-win outcomes. Put simply, if we can help make progress with Israelis and Palestinians, Hutu and Tutsi in Rwanda, or the FARC and the regime in Colombia we should be able to do the same in the United States. Because we have worked on identity issues, poverty, gender, and the environment in places like Burundi or Belize or Bhutan, we should be able to help build broader coalitions in Baltimore or Birmingham or Beloit.

The ADR community bring a different skill set to the table. I’ve recently become involved in the United States Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation Movement which is a multipronged effort to do what its name suggests. The activists we are working with already do terrific work both at the grassroots level and here in Washington. However, some of us at GMU’s Carter School have been asked to join the initiative because we have decades of a different kind of experience in restorative justice, mediation, perspective taking, and dispute resolution itself.

You can see what I mean by considering a slightly modified version of Chad Ford’s key point in Dangerous Love, which is by far the most inspiring peacebuilding and conflict resolution book that I’ve read in years. Drawing on his years of experience with Peace Players International, the Arbinger Institute, and in his own mediation practice, he stresses the importance of taking the first step toward the person one disagrees with and treating them with dignity and respect. Then, we can hope to help the people we disagree with become more open new ways of thinking and to new options for solving the dispute.

You can see what I mean by considering a slightly modified version of Chad Ford’s key point in Dangerous Love, which is by far the most inspiring peacebuilding and conflict resolution book that I’ve read in years. Drawing on his years of experience with Peace Players International, the Arbinger Institute, and in his own mediation practice, he stresses the importance of taking the first step toward the person one disagrees with and treating them with dignity and respect. Then, we can hope to help the people we disagree with become more open new ways of thinking and to new options for solving the dispute.

Ford’s examples are drawn from instances in which a conflict spans an important social or ideological divide—blacks and whites in the US, Israelis and Palestinians, Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland.

What I’d like to suggest here is that we can also take the first step and turn toward the people in today’s social movements whom we typically agree with on the issues, join forces with them, and help build support for both their movements and our own.

As you will see shortly in a series of music videos, those movements could and should benefit from our ability to build trust, foster consensus, and dig into the underlying structural and cultural causes of today’s problems which can in turn lead to a broader paradigm shift in the ways we deal with conflict in general. That is most likely to happen if we engage as peacebuilders within those movement. As my friends at Build Up like to put it, we have a lot to offer when we are both non-neutral and non-polarizing.

There is one way in which the pivot is difficult. We have to put the movements themselves first, for instance, in ways I will be illustrating musically toward the end of this post.

Once we do, the movements will do better and the people we work with will come to see power of our values and add them to their work and help bring about the kind of cultural paradigm shift I’ve been ranting about since I was an undergraduate back in the Dark Ages. Two of those ways stand out at this early point both in the pivot and in my own thinking about it.

Getting There: Rediscovering Our Roots

At this point, it is important to consider a political and professional pivot many of made in the 1980s when the modern field of conflict resolution and peacebuilding began to congeal.

Here, too, I am going out of character and choosing my words carefully. Before then, people were interested in peace and in conflict resolution. However, it was only in the 1980s that a few intellectual entrepreneurs began bringing them together—in Getting to Yes, what is now GMU’s Carter School, Search for Common Ground, and, in my case, the Beyond War Movement. We got there because a few of us found a way to fuse the experiences we had had in earlier protest movements with some ideas that were emerging in pathbreaking research on organizational dynamics and conflict resolution.

Much of it happened by accident. The founders of Beyond War all but stumbled onto the overlap between peace and conflict resolution after experimenting with a bunch of other issues. John Marks created Search for Common Ground after looking for constructive paths forward after becoming disillusioned both by the politics of Vietnam and the “gotcha” beliefs underlying the left. Others got to conflict resolution (if not peacebuilding) by building off initiatives in psychology and labor relations (George Mason), the law (Harvard Project on Negotiations), and organizational behavior (Peter Senge and MIT’s Center for Organizational Learning).

For reasons that would take me way beyond the scope of this blog post, we started going down a different path in the 1990s which continues to this day. Without being fully aware of it, we turned inward more than any of us would have had we been asked or thought about it in at least two ways.

First, we professionalized. That’s easiest to see in academe where it is common to talk about the field or even of the canon. At the turn of the century, the Hewlett Foundation sped these processes up when its funds led to the creation of both AfP and ACR, both of which I have enjoyed being a part of. Even governments got involved both at the national and international levels when development agencies added peace and conflict to their portfolios and some even created explicitly peacebuilding oriented institutions like the United States Institute of Peace where I also have spent many productive hours.

Second, we began to lose sight of the fact we are at our best as both a dynamic academic field and a force for social change when our gaze is directed outward at least as much as we look inward as we professionalized the field. We lost a good bit of our edginess at least as far as working for social change here at home was concerned. That was especially true for us at AfP which we explicitly created as a network of American-based organizations that did their work abroad.

Though I think she overstates her case some, we all entered the world Séverine Autesserre so poignantly describes in Peaceland. We became part of the machine, whether that was in becoming dependent on government funding abroad or working within the legal and corporate systems at home.

This was by no means a bad thing. Without it, we would not have found our seat—however fleeting—at the grownups table. I personally would not have been welcomed with open arms in a decade of working with current and retired military officers. Terms like win/win would not have become part of our everyday lexicon.

Yet, it did leave us a bit flat footed when it came to responding to the issues of the twenty-first century and the conflicts here at home almost all of which antedated the Trump presidency but whose importance took off since the 2016 election.

That’s why the peacebuilding pivot is so important.

Some Musical Examples

I could go on and make that case using examples (good and bad) from my own work.

In the end, though, I doubt I’ll be able to convince you using evidence alone, because pivots of this nature are actually emotionally more than intellectually driven events.

So, let me transition and illustrate what I’m saying by showing how people who are far more creative than I am have repurposed three songs from the 1960s first in the 1980s and then during the Trump administraiton. My goal is not to wow you with my musical knowledge or brag about my generation’s contribution to rock history, little of which I listened to at the time or now.

Rather, I want you to see how these musicians married movements for social change with new metaphors for problem solving and produced electric results.

The first two clips are from Billy Joel’s tour of the Soviet Union in 1987. In the first clip, you will see that he had gone to Moscow and Leningrad planning to perform his version of the Beatles classic, Back in the USSR,

You can see the preparation in the choreographed moves. More importantly, you can see the enthusiasm in the crowds, something I definitely had not seen three years earlier when I took group of college students on a study tour just as Gorbachev was beginning his reform efforts.

The second clip reflects a nearly spur of the moment decision on Mr. Joel’s part to sing his version of Bob Dylan’s The Times They are a Changin. As he says in the clip, the song had rambling around in his head because it described the USSR of the 1980s as well as it did the United States of his youth twenty years earlier. There’s evidence of that in the fact that he sings it unaccompanied and without the pre-planned hoopla of Back in the USSR. That’s evident in the fact that he got some of the words wrong and left out one of the most important verses.

For our purposes here, my point is the same. Both songs worked because they spoke to substantive issues of the times more than they did to the processes of conflict resolution. Indeed, Joel’s tour was part and parcel of efforts initiated by the like of Roger Fisher’s teams at Harvard, Search for Common Ground, the Carter School, and Beyond War which did the first ever televised spacebridge between the US and USSR and published the first ever political book by Soviet and American authors.

We lost some of that excitement in the years that followed for reasons that go beyond professionalization. We also lost our connection to those movements for social change that brought so many of us into both wings of this field that I work with today.

The kind of pivot I’m calling for here would involve rediscovering our roots in social change and immersing ourselves in the kinds of movements that will, in Dylan’s terms, “shake your windows and rattle your walls.” Many of us remain politically engaged as citizens but not as much as we used to be in our professional work.

Given the events of the last year or so, the objective circumstances on the ground are demanding that we find ways of being in Build Up’s terms, “non neutral and non polarizing.”

Now, fast forward 30 years to 2018. The most recent school shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School has killed seventeen. This time the survivors are high school students who are willing and able to react politically.

A mere six weeks after the tragedy, the March for Our Lives was held at sites around the country, including a rally that drew at least a hundred thousand people to Washington. As the rally drew to a close, Jennifer Hudson led a choir through a very different version of Bob Dylan’s song.

As different as it may have been, it was no less powerful than Dylan’s original or Billy Joel’s repurposed version in the 1980s precisely because it spoke to the emotions of the moment.

In fact, it may have been even more powerful because it brought the song back to its home turf. The audience the singers wanted to reach that day were the same people Dylan wrote about in the full stanza I alluded to earlier:

Come senators, congressmen

Please heed the call

Don’t stand in the doorway

Don’t block up the hall.

For he that gets hurt

Will be he who has stalled.

There’s a battle outside and it’s ragin’.

It’ll soon shake your windows

And rattle your walls.

For the times, they are a changin’.

Except that this time peacebuilders weren’t (yet) present in that movement, although many of us (including my wife and me) were there that day—albeit in our capacity as citizens as noted a few paragraphs ago.

It shouldn’t be hard to get there, a point I will make next in ending this post. It is not hard to update our language and bring it into today’s movements and benefit everyone. It will require us to heed the lesson of yet one more repurposed piece of music..

In 1970s, the supergroup, Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young included Teach Your Children on their Déjà vu album. Graham Nash, its author, then set created a new set of video montages for it after the March for Our Lives protests in which the visual images shift from the 1960s to the 2010s just as the lyrics shift to teaching your parents well.

Therein lies perhaps the most important and most controversial message in this post. People may have once been young and I, for one, would have loved to have had parents who taught me well in CSNY’s terms.

But now, I’m not just a parent, but a grandparent. As today’s photos of the rock and roll icons I’ve mentioned show, we’re all old and have left Ringo Starr’s concern about “when I’m 64” well in the rear view mirror.

As Mr. Nash suggested when he wrote the song in the 1960s, it’s time for today’s kids to teach their parents well.

It Can Happen Because It Is Already Happening

That leads to my final point.

The pivot is already happening.

It’s not being led by my generation of peacebuilders but by our political children and grandchildren.

It had already begun before the onset of what Lawrence Wright called plague year in his stunningly depressing article in The New Yorker’s final issue of 2020 (and which will appear in book form in June).

Blissfully ignorant of what was going to happen a mere six months later, AfP and my publisher, Rowman and Littlefield, organized a three day workshop on expanding our impact where people currently go when they face conflict.

About 50 peacebuilders from around the country gathered at George Mason to grapple with a contradiction. I quickly realized that without thinking about it, we had invited lots of young activists who wanted to go beyond what those of us who organized the event had been doing. They helped us see that while our impact has grown, it is not what we want it to be.

For example, more than 200 community mediation centers belong to NAFCM. However, most people do not take their conflicts to those centers or other trained mediators. Instead, they are more likely to turn to social workers, schools, the clergy, coaches, and even the police. I started calling them our “first cousins” and pointed out that many of them had training and skills that overlapped a lot with ours even though they rarely self-identified as either peacebuilders or conflict resolution specialists.

The attendees realized that we had to pivot away from primarily trying to build those movements around building support for our work. As a number of people at the workshop put it, we next had to build coalitions with those people who were already doing something like our work and were, in essence, peacebuilders or conflict resolvers without really knowing it. In my informal terminology, we had to meet our first but somewhat distant cousins.

After the pandemic hit, most of the work we envisioned, per se, had to be put on hold. Nonetheless, we made some progress on individual progress, including one involving redefining high school history and civics curricula and a number of pilots for bridging the red/blue divide around concrete issues.

As I wrote last week, those young peacebuilding entrepreneurs are already pivoting. They already are on the front lines of movements to combat climate change, systematic racism, sexism, economic inequality and more. Many of them are there as peacebuilders in organizations like Build Up (for transparency’s sake, I sit on their board), Urban Rural Action, Resetting the Table, The Hive, and the Mindbridge Center.

It’s time for the rest of us to join them.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.

Also published on Medium.