Last week, I had the pleasure and privilege of hosting my coeditors Franco Viccari and Miguel Diaz along with three of the other authors at a launch event for The Rondine Method to the Alliance for Peacebuilding’s office. We then went on to a delightful lunch hosted by the Italian Ambassador, Mariangela Zappia.

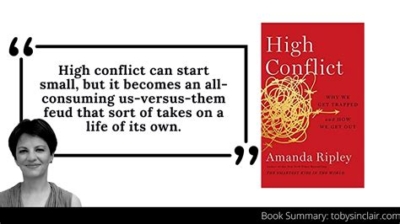

Book launches are rarely earth shattering events, but this one was different in two ways. First, the Rondine method is remarkable but largely unknown ib the wider peacebuilding world which is the only reason I agreed to edit the book with Miguel. Second, my friend and colleague, Amanda Ripley, spent a few minutes with me after the Q and A period wanting to know how it and other tools could be used to address the psychological drivers of the polarization dividing the United States, Italy, and the countries which Rondine students come from.

I promised her I’d spend the weekend thinking that through and use this week’s blog post to take a first stab at the problem. Once I had finished reading Maggie Clark’s new book, Uncertain.

Rondine and its Method

Rondine is a totally self-contained village just outside the Tuscan city of Arezzo. For a quarter of a century, each fall it has welcomed cohorts of 20 or so university graduates from war torn countries around the world. Although they don’t know each other before they arrive, there are normally pairs of students from both sides of one of those conflicts.

The program is highly selective because Vaccari and his team want to create what they call the next leaders for peace. The students who ultimately are selected spend two years living in the village and earning a graduate degree at a local university all at no cost to the participants.

They spend the next two years learning about conflict resolution and, more importantly, about learning how to live with each other. For our purposes here, it is those final words that are the most important.

Most (but not all) dramatically change how they view “the other” with whom they have chosen to live. It is never easy. It is particularly difficult if the conflicts in the “real world” flare up as they have for the Israeli and Palestinian students currently living there.

That’s where the Rondine method’s magic comes into play. It isn’t that Franco Vaccari and his team have some sort of wand that they can wave and instantly overcome a lifetime and even decades of trauma.

Rather, the method is based on the insights Vaccari has gained from his career as a clinical psychologists which drive what the team seeks to accomplish. In his words, thinking in terms of the other as an enemy turns members of the “out group” into a scary mirage, a ghostly apparition, or even a hallucination. The students spend the two years literally getting to know and learning how to live with at least one member of their presumed enemy.

What Vaccari calls a relational approach to conflict often begins when the students arrive. If a Palestinian student is about to arrive in the village, they are met at the Arezzo railroad station by the Israeli student they will be living and working with. Those meetings often are tense. Things don’t get any better if what Vaccari calls a “relational shock” like the October 7 Hamas attack occurs. Although some students do choose to leave when something like that happens, most don’t. Most learn to see the real humanity in “the other” and, by the second year, they begin planning a project they will carry out together after their return.

In the terms that I’m increasingly using in my own writing, I’ve never seen a peacebuilding organization that better helps its participants go to scale inward. The dozen or so former students I’ve met (including Phil in the picture at the top of this post) rave about how Rondine has changed their lives.

Amanda’s Question—Which We Should All Be Posing

That takes me to Amanda’s question, which is also one I’ve been posing since I first met Franco and his colleagues in the year 1 BC (otherwise known as 2019). Rondine does a terrific job of overcoming the psychological forces that drive societies apart at an individual level and for young people who come there with at least a vague commitment to overcoming those mirages and hallucinations.

But what, she (and I) wondered, does it have to teach the rest of us who don’t have a village of our own (replete with a thirteenth century castle tower) at our disposal?

Of course, she knows parts of the many answers to her own question. As she has put it, her own colleagues can help by both complicating the narrative away from simple stories of good v. evil and by replacing them with others that combine hope with curiosity and agency as she puts it on her web site.

But there is more that we can learn from Rondine. I’ve spent much of my time since the start of the COVID pandemic learning about other psychotherapeutic approaches to conflict resolution and personal growth. One of my former editors told me about Six Seconds which led me to look at other mindfulness related approaches, including Optimal Work, one of whose young staff members was at our launch event.

What I hadn’t quite realized while talking with Amanda is that most of these organizations do not see themselves as peacebuilders or speak directly to political woes. Maggie Jackson spends the bulk of one chapter focusing on the Leadership Lab and its use of deep canvassing in building support for marriage equality and other progressive issues.

More generally, her book and its title tell us a lot. Uncertainty is a valued asset to bring to our uncertain world, especially in difficult conversations. It’s important to remember that you don’t have all the answers. No one does. And maybe, just maybe, you have something to learn from that person you disagree with.

That point gets driven home in another book written by another new friend, Saleema Vellani, Innovation Starts with I. Early in the book she makes a bold statements:

When I changed my relationship with myself, it was incredible to experience the immediate transformation of my relationships with others. I started attracting people and opportunities aligned with my values and who I was becoming.

Saleema’s primary audience is made of up of private sector innovators, but her logic holds for peacebuilders and has been reinforced in recent works by both David and Arthur Brooks. How I present myself to the people I am odds with matters. If I treat them with scorn and are seen to demean them as human beings, I’m only going to drive them farther away. But since innovation does start with I, the more self-aware I am, the more I present my true self, the more I emphasize Amanda’s curiosity, the more like my interlocutors are to engage. They may not agree with me, but at least they will see me more as someone of interest and, in time, someone they can work with. And as both Brooks have argued, even if my adversaries do not respond in kind, the evidence is clear that I end up feeling better about myself and the world if I approach them with what we used call a spirit of good will in my Beyond War days in the 1980s.

The key to all of these individuals and organizations is that they start by accepting people as they are in ways that Vaccari and his team would recognize. The Leadership Lab, in particular, goes out of its way to have unscripted talks with people who are on the other side of whatever issue they are working on. Even more importantly, they treat the people they meet with respect and with Amanda’s curiosity. Or, to use Kelly Corrigan’s catch phrase, they keep asking the people they meet to “tell me more.”

But in a way, Rondine goes farther because it has put its organizational finger on a key factor that often doesn’t get it due in the networks that are trying to defuse tensions in the United States. Rondine starts by asking all of the people in a troubled relationship to rethink the way they act. They’ve learned the lesson that the folk singer Tom Paxton introduced me to it the early 1970.

We need peace, and let it begin with me (because) my own life is all I can hope to control.

All too often, we enter discussions about defusing tensions and the like with the assumption that it is “the other” who has to change. All to rarely do we ask how we contribute to the situation ourselves. “I” and “we” are rarely blameless.

It is not easy for someone with views like mine to be nonjudgmental when dealing with an avid supporter of former President Trump. Yet, if Rondine is right, that is exactly what I have to do. I don’t have to give up my commitment to sustainability or racial justice or anything else I hold near and dear. However, I do have to understand that those are what psychologists call superordinate problems which I share with everyone—including the people I disagree with—and that can only be definitively solved if just about all of its are on board with the outcome.

Going to Scale Outward and Upward

How we get there, of course, is a different—and far more difficult—matter.

Luckily, the discussions I’ve had since the launch at AfP and the embassy have pointed at least one way forward—working with high school students. It turns out that my coauthor, Patricia Shafer, is the driving force behind Youth and Peace in Action which h is the largest peacebuilding group working with teenagers in the United States and the Caribbean. Rondine has recently turned its small program for Italian high school (liceo) students into a nation-wide pilot with programs in over 80 schools around the country.

High school students alone won’t solve all of the world’s problems, but they are good place to start along with other civil society organizations that seek to build what Robert Putnam calls bridging social capital that strengthen ties across ideological and other deep divides.

These discussions are just beginning, so stay tuned, because I will keep writing about them especially as they find their way into the book Patricia and I are writing, tentatively entitled Peace is a Verb.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.