Changing the (Coronavirus) Narrative

In the 1980s, the hundred or so members of the national leadership team of the Beyond War Movement spent a weekend discussing the seemingly simple statement, “reality tells me what to do.” Once we were a half hour into the discussion, we all realized that those six simple words did not lend themselves to anything like simple conclusions.

I thought about that weekend a year or so ago, when I read a remarkable article by Amanda Ripley on complicating the dominant narrative(s) regarding conflict resolution and peacebuilding. I found myself returning to her theme and the question of what reality is telling me what to do while I struggled to find a good way for peacebuilders (and the rest of us) to respond to the coronavirus pandemic.

After more than a month of running into intellectual dead ends about to do so in these troubled times, I think I finally figured out one way of moving forward. I finally figured out a way to shift the narrative about how we could and should do our work as peacebuilders and more in the light on the pandemic.

Brilliant’s Brilliance

Oddly enough, it came after I thought through the implications of a remarkable TED talk by the esteemed physician, Larry Brilliant. As I pointed out in last week’s post, the TED Daily podcast has added interviews on the pandemic and its implications, most of which are hosted by its CEO, Chris Anderson, which I listen to on my daily masked walks around the neighborhood.

Oddly enough, it came after I thought through the implications of a remarkable TED talk by the esteemed physician, Larry Brilliant. As I pointed out in last week’s post, the TED Daily podcast has added interviews on the pandemic and its implications, most of which are hosted by its CEO, Chris Anderson, which I listen to on my daily masked walks around the neighborhood.

Dr.Brilliant had won the 2006 TED Prize in honor of a talk he gave on pandemics. He used the cash award to create INSTEDD, an organization that tries to detect and deal with public health and other disasters through what he then (and now) called rapid detection and rapid response.Since then, he has done a lot of things, including contributing to the screenplay for Contagion, a film that has not surprisingly gotten a lot of attention again these days!

As I listened to the 2020 talk, I realized that we could take the five themes he focused on, flip them on their heads, and begin seeing paths forward on a whole host of issues. We may not be able to take a lot of active steps in those directions now. However, we could and should should begin planning to do so now.

While he talked about the forces leading to rapid detection of and rapid response to the pandemic, I’ll spend the next four weeks talking how we can rapidly detect and rapidly respond to the global issues that already existed but that this crisis brought closer to home, including those I’ve spent the last half century working on and. Here, you will see how his first three themes help us see how a movement can grow, while the final two call on us to rethink the very issues we focus on.

I know that I don’t have it all right. However, I am convinced that the bottom line is clear. It’s time to put peacebuilding–or whatever issue(s) you have focused on–in a broader perspective and work on them together by reframing the narrative beyond the crisis of the day, whether that’s the pandemic or the conflicts roiling the world. None of these ideas are new, let alone uniquely mine. However much we may have nodded agreement to them in the past, the pandemic is showing us that we need to take them far more seriously today.

And, I definitely including myself in that “we” of the previous sentence.

Spoiler Alert

If you want a preview of where these four blog posts are heading, check out Kelly Corrigan’s “Brief but Spectacular Moment” from the PBS NewsHour on April 29,2020. It makes me smile and helps me focus this series of articles each time I watch it because she talks about imagining a better post-pandemic world and how we “hit it” in making it happen.

R Naught/R0

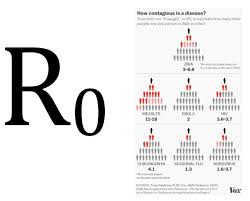

The first one gets at why flattening the curve is so important. As epidemiologists see it, the rate at which a disease spreads starts with what they call its R naught or R0 if you prefer mathematical notation. Put simply, that’s the average number of people who are infected by someone who already has the disease. No one, in fact, knows what that rate is for COVID-19 because it is a new disease and we have done a lousy job of tracking its spread. Brilliant estimates that it is at least in the range of two to three, which means that each person who has the virus infects two or three more people.

The key here is that that the number is greater than one in the United States and most other countries today other than South Korea, New Zealand, and a couple of others. Let’s assume that Brilliant’s lower estimate is more or less accurate which means that each sick person infects two more who, in turn, each infect two more, and so on. In the simplest terms, as long as R0 is greater than one, the disease will spread exponentially as the Image at the top of this post suggests. Once we get that number below one and keep it there, the number of new cases will decline and, if all goes well, eventually disappear.

Now, for a moment, stop thinking about the spread of a disease and do what I referred to as “flipping the measure on its head” earlier in this post. In other words, focus, instead, on the spread of new and constructive values and ideas, which I’ll lay out in more detail two weeks from now.

The key is that constructive ideas can spread exponentially, too, ias long as their R Naught is greater than zero. When I first started using this idea (without the meme of R Naught) with the Beyond War movement in the 1980s, we showed the people who attended our training sessions how quickly a movement could grow if each of us reached five or ten people and convinced them to try out what we called a new way of thinking about conflict.

Lots of people nodded their heads, but few of them really took us up on the challenge and started doing their part to spread our benign and even constructive “virus.” Indeed, after the Cold War ended, the Beyond War movement lost its momentum and our equivalent of R Naught dipped way below one. By the end of the 1990s, we disappeared.

Incubation Period

R Naught gets the most attention as we try to flatten the curve. However, his other three points may be even more important as we think about our post-pandemic lives.

To begin with, Brilliant also pointed out that COVID-19 seems to have an incubation period of a few days during which someone can pass the virus on even though he or she has not yet developed any of its symptoms. The fact that it has a relatively long incubation period makes its R Naught particularly worrisome because the virus can spread without the infected person or the others s/he infects even being aware that it is spreading.

This time, flip the narrative and think about how quickly how quickly constructive can spread. In that case, the longer the “incubation period,” the lower our potential impact. How do we seize on the urgency of the moment to get people to see that there are things they can do to—in this case—make a difference on any of the dozens of issues that will roil our post-pandemic world.

Let’s leave how we can speed up our “desired” incubation period for a later post.

For now, simply note that new ideas (like viruses) can spread to a population at various rates of speed.

Target Density

It is hard not to notice that the virus has spread more rapidly in cities than in rural areas. As with most aspects of the pandemic, there are many reasons why that’s the case. However, near the top of any list is the fact that people simply interact with each other more in crowded cities than they do in the countryside. They are, in other words, more likely to encounter and be infected by someone who already has the disease.

The importance of that kind of density extends far beyond this disease. Interacting more often with more people is part and parcel of our globalizing and interconnected world. And, just like R Naught, the spread of a virus grows exponentially as the density of our social networks with their direct and indirect connections grows.

As the power of social media has shown us, that’s not just true of the spread of epidemics. It is easier for new ideas or memes or “go viral” for the simple reason that we are more connected to more people in more ways than ever before in human history. And, our world looks increasingly like the network depicted here in which we are interconnected through incredibly complicated sets of relationships in which what I do influences everyone and everything else.

Again, I’ll leave the details for the next three posts. Here, once again, it is enough to note that the same dynamic holds for constructive ideas as well as for destructive viruses.

Spillover

Perhaps the most important lesson Dr. Brilliant leaves us with lies in what he calls the spillover effects of the pandemic whose implications cover what we should be talking about more than how we go about building a movement, which is what I have been focusing on so far. Note that here I do go far beyond what Brilliant actually said, but I do so in ways that I know are consistent with his thinking about the world in general.

As far as epidemiologists are concerned, COVID-19 is one of many “spillover” diseases that first infected animals and, only later, “spilled” over to human beings.

However, as Brilliant implied, it spills over in other ways by revealing other human problems that get shown in a new light as we grapple with the disease. To cite but the most obvious:

- Why is the virus taking a heavier toll on people of color and the poor?

- More generally, what does it tell us about all the forms of inequality in modern life both with countries like the United States or between the Global North and the Global South?

- Or, how is the pandemic intensifying conflicts and other problems around the world?

- Why are some governments better able to craft coherent solutions?

- Why is it so hard to think about the epidemic as a reflection of the realities of our globalizing and increasingly interdependent world?

These are the kinds of questions that we will have to deal with once the pandemic ends. Many of us already were working on them. Now the current is showing us that we need to both deal with them with new urgency and see them in a new in which they are part of a larger, global crisis of which pandemic itself is just one symptom.

We’re In This Together

Brilliant has long championed what he calls One Health or an approach to medicine that treats all of life as part of the same interconnected system. That, of course, includes the growing number of spillover diseases, but also the interconnections among human health systems whether they are in Wuhan or Palo Alto or Cape Town or Syrian refugee camps.

Here, it is worth quoting Brilliant himself.

We will not be able to conquer a pandemic unless we believe we’re all in it together. This is not some Age of Aquarius, or Kumbaya statement, this is what a pandemic forces us to realize. We are all in it together, we need a global solution to a global problem. Anything less than that is unthinkable.

Many of us have been using phrases like “all in it together” of late, including my local CBS affiliate and Zoom’s web site. Some of us, too, have been using similar tag lines for decades.

Now that we are really seeing those interconnections shape our daily lives in unprecedented and tragic ways, maybe we’ll learn our lesson and begin acting as if we are, in fact, all in this together.

Maybe.

Next Steps

Over the course of the next four weeks, I will write blog posts that explore these ideas in more detail.

May 1 Changing the (Coronavirus) Narrative

May 8 New Principles to Live By

May 15 Going to Scale in Three Ways

May 22 Empowering the Seemingly Powerless

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or positions of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.

Also published on Medium.