Going to Scale

This is the third of four blog posts that explored the things we could and should do if we want to spark broader social and political change in the aftermath of the corona virus pandemic. During these confusing times when we have had to stop or at least dramatically alter the work we were doing, I’ve used the time I’ve spent sheltering in place to think about the implications of the COVID-19 epidemic for the work I’ve been doing for the last half century. Now, it’s time to put some of those ideas into practice.

May 1 Changing the (Coronavirus) Narrative

May 8 We’re In It Together

May 15 Going to Scale

May 22 Nailing It

I ended last week’s post with the idea that we will have to build a movement or movements that echoes the increasingly popular internet meme–build back better to which I added the word bigger. Even more importantly, I suggested that the movement(s) will have to cover all the silos we currently work in, integrate them, and lead to a demand for broadly based social change that goes beyond world peace, ending climate change, ending inequalities and all of the other goals we hold near and dear.

Given the current state of affairs when we are struggling to deal with a single unexpected crisis in the COVID-19 pandemic, taking on even more sweeping challenges might seem foolhardy. However, the evidence I outlined in the previous two posts paradoxically suggests that the current sense of pessimism also presents with a golden opportunity to embrace more audacious goals that could have far more sweeping outcomes than any of us really thought possible as recently as the beginning of this year.

I will make that case here in four steps that will take us from that kind of general need to the specific things that we peacebuilders could and should do:

- The need for a movement or movements with more sweeping goals precisely because of the bind(s) we are currently in

- Such an effort will require “going to scale” in three rather different but overlapping ways

- What we know about the ways these kinds of movements grow

- The critical role that peacebuilders will have to play

The Job to be Done

I’m not going to be the person who creates or leads any such movement. That’s a job for someone who is more creative and connected than I’ll ever hope to be.

At the same time, I can outline what the movement will have to be like.

That starts with something I learned from the work on the late Clayton Christensen who taught and wrote about disruptive innovation from his position at the Harvard Business School. In almost everything he wrote including the book length version of his last class of the semester, he stressed what he called the job to be done.

In our case, that means addressing the interconnected “wicked problems” which the pandemic has forced us to confront. As I said last week, it is now far easier to see how related public health, climate change, conflict, gender, inequality, and governance are. It is far easier to see an effective movement for change has to tackle all or most of them in two main ways.

The first involves shifts in the corporate community. My friends Nik Gowing and Chris Langdon of Think the Unthinkable have done a great job of pointing out how unprepared we are. They also pointed me toward the B-Team and its Imperative 21 initiative which brings together a network of high-end business leaders who agree that

Capitalism must work for all of us and for the long-term. Imperative 21 is a business-led, cross-sector coalition working to align incentives and shift culture so capitalism works for the benefit of all stakeholders. Together, and with others, we will support business and finance leaders who are ready to turn bold promises of a new corporate purpose into meaningful action.

It’s not just the B Team. While I was writing this post, I devoured Reimagining Capitalism by Harvard Business School’s Rebecca Henderson, which makes those points in a data-drive and systematic manner. And it’s not just Henderson. HBS’s faculty has been dotted with luminaries who’ve been making the case for equitable change for years, including Christensen, John Kotter, Amy Edmondson, and more.

There are also signs that the nonprofit and the philanthropic community is becoming more proactive. Interaction and a number of other European and American based NGOs have recently published a set of statements on the future of civil society organizations. Interest in impact investing and the like were already bubbling up before the outbreak of COVID-19, but major foundations like Kellogg and Rockefeller are in the process of dramatically expanding their ambitions and the scope of their projects. You can hear the way those two foundations are expanding the scope of their work and their ambitions by listening to the last two thirds of the May 12, 2020 edition of the WBUR/NPR show On Point.

The second involves traditional social movements that operate from a very different starting point than either the people who think in terms of B Teams or occupy C suites. Most insurgent movements—including many that I’ve been a part of—assume that the only way to get new ideas adopted is to start on the fringes of society and public opinion and force the people in power to change their ways. We may not have enjoyed the kinds of success that members of the B Team have, but there’s little question that dissatisfaction with the status quo is at an all-time high.

My generation may perhaps deserve derisive memes like “OK, Boomer.” Even if that’s true, I see echoes of the anger my generation showed fifty years ago in the frustrated students and other young people I work with today.

If I’m right, the next movement will have to incorporate both of those strategies.

If I’m right, the next movement will have to incorporate both of those strategies.

Lessons From Two Mentors

Oddly enough, I’ve been trying to combine these kinds of approaches since I first encountered two of my intellectual mentors when I was in grad school at the University of Michigan in the first half of the 1970s.

I was drawn to Charles Tilly because he was asking questions that made sense to those of us on the new left. Chuck literally threw his house open to a generation of students who were interested in how social movements succeed. Indeed, he and I spent the next thirty years in on-again-off-again debates over whether nonviolence could lead to sweeping change. We did agree that successful movements built broad coalitions that transcended geographical and issue-based boundaries. To cite but two examples from those days, there was no single civil rights or anti-war movement. They had the impact they did because brokers like Bayard Rustin and Allard Lowenstein helped often fractious groups cooperate enough to challenge the state as Chuck loved to put it.

I was drawn to Charles Tilly because he was asking questions that made sense to those of us on the new left. Chuck literally threw his house open to a generation of students who were interested in how social movements succeed. Indeed, he and I spent the next thirty years in on-again-off-again debates over whether nonviolence could lead to sweeping change. We did agree that successful movements built broad coalitions that transcended geographical and issue-based boundaries. To cite but two examples from those days, there was no single civil rights or anti-war movement. They had the impact they did because brokers like Bayard Rustin and Allard Lowenstein helped often fractious groups cooperate enough to challenge the state as Chuck loved to put it.

At the time, I did not pay enough attention to Everett Rogers even though his office was literally down the hall from mine for at least a year. His importance only became clear to me when I joined Beyond War a decade later and we developed strategies for producing social change that begins with the adoption of new ideas and values in mainstream ways rather than through what Tilly and his colleagues called contentious politics.

Indeed, the Beyond War leaders were drawn to Rogers because they had seen the power of his work in expanding the sales of the Silicon Valley companies most of them worked for and that some of them had created. As the chart here suggest, Rogers was convinced that the adoption of new ideas follows a regular pattern. At first, only a few innovators bought them. Gradually, however, people with better communications skills and, especially, respected local leaders came on board. Once an idea had reached enough of those people and had been accepted by about five percent of a society, Rogers called it embedded. At about 20 percent, he felt it was unstoppable.

Our challenge today is to combine the insights from these two perspectives of on social movements.

Tilly’s strategy focuses on how we work from the “outside in” to challenge the status quo. Rogers suggests we can produce profound change by working from within.

Activists have often seen these two (and other) approaches as opposites. Today, I’m convinced that we need to build coalitions that will be built using both of them. Yes, pressure has to put on reluctant leaders, which is the most charitable language I can use to describe not just the Trump administration but most of the leaders in the world today. At the same time, the coalitions can be built based on Rogers-like new ideas that are already showing signs of being embedded today as I tried to suggest in last week’s post.

Going to Scale In Three Ways

To borrow a term from the startup world, this is all about the need to take our work to scale in ways we barely even dreamed of a few short months ago

Neither the B-Team nor the philanthropic community nor today’s social movements alone can get us there. That’s where a new movement or movements will have to come into play

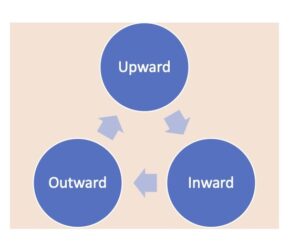

Going to Scale

As my chart (which demonstrates that i’m not a good graphic artist) suggests, going to scale has to take place on three levels that build on each other. Their interconnections certainly will not unfold as clearly or as smoothly as this simple diagram might suggest. Nonetheless, there will have to be a constant and conscious interplay among them, which is not something that any of the organizations or thought leaders I’ve mentioned so far are particularly good at.

- Upward. In the end, we do have to change public policy. As I’ve learned from living in Washington for more than twenty five years, that does not happy simply because a group of policy analysts develop new strategies and proposals. To be sure, we need the likes of the B Team who speak the language of power and have access to key decision makers. But the rest of us need to understand that policy changes arise out of a mixture of expertise and outside pressure, which is why going to scale involves the other two arenas as well.

- Outward. Here, I’m thinking of grassroots activism in at least two ways that together make going to scale upward possible. When the pandemic began, I was making plans to build networks of student and community activists that would begin in specific places and spread around the country, which is one way of thinking about going to scale outward. Since then, the pandemic has shown me that it is even more important to build outward in a second sense—by building coalitions that cross substantive lines, treat the problems we face from a holistic perspective, and help people see that we can’t resolve answer any of these tough questions unless and until we focus on all of them.

- Inward. Many of the people I work with talk about the need for a cultural change in which Americans and people around the world adopt new norms that are in keeping with the interdependence of today’s world. That’s why phrases like “we’re all in this together” are so important. That said, I’ve also realized that those of us who are leading these efforts have to change ourselves as well as asking others to shift their norms and priorities. I was lucky to have returned to activism through the Beyond War Movement of the 1980s that made its volunteers explore the personal as well as the political implications of what we were doing. That kind of constant introspection has led me to see the need for everything from empathy to my own integrity. It may well be that many activists who are drawn to the upward and outward sides of the work will not have the time or energy to be all that introspective. However, my experience suggests that at least the leaders have to do just that.

The Peacebuilder’s Role

I have spent my adult life as an activist and educator promoting large scale, non-violent change. I’ve also argued all along that we need to do more than “just” build peace. Now, it is clearer than ever that building peace alone will not be enough and that we peacebuilders will have to work in the kinds of broader coalitions discussed above

At the same time, it seems clear to me that the peacebuilding and conflict resolution community will have a critical role to play in making it happen, assuming, of course, that it does happen.

Let me illustrate that with two examples, one of which speaks to our field as a whole and the other to one of its practices that I’m personally involved in.

Building Agreements. Our most important skill is our ability to get people who disagree find common ground, if not a total agreement. It’s no accident that the most widely read book in our field is entitled Getting to Yes. We can point to highly publicized success stories in South Africa and Northern Ireland. But, there are plenty of other lower profile examples in individual communities and companies. Even when we haven’t produced sweeping agreements, we’ve made substantial progress in all three of the areas in which we need to scale up. Convergence Policy, for example, has done terrific work on divisive national issues. Next Gen Peacebuilders has mobilized thousands of GenXers in the United States and around the world. Peace Direct is one of dozens of NGOs that stress the importance of local peacebuilding. Build Up^ works at the intersection of peacebuilding, technology, and the arts. Search for Common Ground works in dozens of countries around the world and does everything from conducting Track Two diplomacy to making television soap operas that stress conflict resolution themes. There are now at least two hundred academic programs in the English speaking world that lead to undergraduate or graduate degrees. And these are only the ones I’ve worked the most closely with.

Reconciliation. While all of us work on projects that take us toward “yes,” not all of us work on reconciliation, which may be the single most important skills set we “bring to the table” As we’ve already seen, the coronavirus pandemic has touched lots of raw nerves and deepened some already deep divisions, especially here in the United States. However, as the peacebuilders in South Africa understood, we are all going to live with each other once the pandemic ends and, hopefully, once we have made the policy and cultural changes mentioned earlier. However that happens, some of those divisions will still exist and others will emerge. Peacebuilders will be called on to both help solve the problems and find constructive ways of living with each other—whatever our differences. Initiatives like the dozens of truth and reconciliation commissions that have been created around the world do not magically make ideological and other differences disappear. Instead, they have led people on both sides of the dispute explore their current and historical grievances together, understand each other, and find ways of moving forward. Reconciliation will be particularly important in countries like the United States since we peacebuilders ourselves often find ourselves on one side or the other of disputes. I, for example, disagree with just about everything the Trump administration has done—and not just on the pandemic. So, we will be asked to practice what we preach, which is one of the reasons why going to scale inward will be so important in the weeks and months to come.

Next Time

There is one thing I do know for sure which also underlies everything I’ve said so far in these three posts.

If we don’t act—you and me—nothing like this will happen.

Yet, we live in a time at which record numbers of people are “convinced” that they can’t make a difference.

I put convinced in quotation marks in the previous sentence because I have spent my entire career helping people see that statements along those lines are simply wrong. Average citizens like ourselves have made a difference time and time again in human history.

So, I’ve left myself with the same challenge I’ve dealt with in ending every book I’ve written. How can I help empower you so that you can find your own way of building this kind of movement that can go to scale in each of these three ways.

That’s what I’ll try to do in next week’s final blog post in this series.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.

Also published on Medium.