Getting (Politically) Unstuck

Remember the last time you felt stuck.

Really stuck.

It might have been because you had a bad habit you didn’t think you could break.

Or an interpersonal relationship you felt you couldn’t get out of.

Or you worked for a company that could not find its way of a rut or, even worse, found itself in a death spiral that was leading toward bankruptcy.

Or most importantly for our purposes here—a community or an entire country that seems incapable of solving (m)any of its problems or seems stuck in a death spiral of its own.

If so, this post might be right up your alley.

If so, this post might be right up your alley.

I’m not all that interested in how you get unstuck and find a way out of your personal dilemmas.

I am, however, interested in how we can we can get unstuck and find a way out of our collective dilemmas, many of which have been around for more entire adult lifetime—and in some cases, longer.

That involves designing paths forward in which we address the root causes of those problems.

And that can only happen if we take a step back from the issues that seem to keep us stuck and see things in a broader light.

Bringing Out the Best in Us

In this first post, Defining the Best in Us, I explore the challenges we face in the aftermath of the 2o20 election.

Support Democracy

Your Content Goes Here

Preventing Violence and Reducing Polarization

Your Content Goes Here

Leverage policy makers

Where do we go from here

Overcoming Obstacles/Moving Toward Reconciliation

In this, the second in a series of posts on how to bring out the best in ourselves as we deal with the tricky political situation we find ourselves in today in the United States, I’m going to explore strategies for getting unstuck. Here and in the next one, however, I’ll be taking a step back from the issues of the day to talk about the importance of adopting broader understandings of how we can get unstuck, assuming, of course, that there is such a word.

As I mentioned in my most recent post, my new friends on the South African team at Reos Partners who were making arrangements for me to meet with Adam Kahane, whose work I had admired for a decade or more. That led to some wonderful conversations with him and the opportunity to read the draft of his next book which will deal with how, as facilitators, we can help the people we work with overcome obstacles. I’m not going to dig into their work in much depth here, because I’ve done so in my review of one of his earlier book, Collaborating with the Enemy,

Instead, I’ll use his ideas as a springboard to talk about how and why we can get unstuck. However, I have to admit that I was having trouble making this post become something more than an analysis of Adam’s ideas until I got an unexpected email ofrom Heidi and Guy Burgess. They commissioned me to write the core article on reconciliation for Beyond Intractability in 2003 had. Since then, they had updated the article on the basis of things I had written and added insights of their own. However, as they pointed out to me in the email last week, it really has gotten way too unwieldy.

So, they asked if I would be willing to rewrite it. I agreed. When I reread the article, I realized three things:

- My own thinking on reconciliation has evolved a lot over the last seventeen years.

- Adam and Reos focus on overcoming the kinds of obstacles that get in the way of reconciliation even though they don’t use that term, per se, all that often.

- Combining insights from Adam here with my ideas on reconciliation in next week’s post would effectively provide intellectual and political bridges to the steps we will be taking at the Alliance for Peacebuilding even before the Biden administration assumes power.

I’m not convinced that Reos or those of us who focus more explicitly on reconciliation have all the answers, and I know of plenty of who have great ideas that could help us as 2020 draws to a close and the Biden administration prepares to take office. Nonetheless, given their focus on overcoming obstacles and the role facilitators can play as change agents, this turned out to be a wonderful moment for me to do a deep dive into their work and get to know their founder, Adam Kahane.

Make no mistake about it.

We are stuck.

We were stuck before we were blindsided by crisis after crisis this year.

Name the issue.

We’ve made limited progress on each and every one of them during this century which is now twenty years old.

Part of the reason is that we have not really come to grips with two key overarching facts:

- We live in a world that is increasingly interdependent and unpredictable that Kahane, I, and others refer to as VUCA (Volatile, U Complicated, Ambiguous) that keeps throwing overlapping or “wicked” problems at us.

- Business as usual has not helped us make much progress on any of them.

Together, exploring Reos’s tools and next week’s focus on reconciliation can help us figure out how to overcome the obstacles that have us stuck.

Or worse.

Transformative Rather Than Adaptive Change

I’ve always admired Reos’s approach because they start with the assumption that we can’t just tinker with the status quo and that we can’t define where we’re heading with any degree of clarity or precision. As my friend Betty Dhamers (and others put it), we can’t just rearrange the deck chairs on the Titanic.

In the simplest terms, there is a disconnect between what we need to do to solve the problems facing an increasingly interconnected and complex world and the tools we have at our disposal to use in solving them.

That leads to another disconnect. On the one hand, we can’t seem to make much progress addressing today’s problems using the policy and political tools that have worked so well in the not so recent past. On the other hand, I’m suggesting we need—and can implement—what Adam calls transformative change.

I’m not convinced that Reos has identified the only way to help us deal with those complexities, but but they certainly have come up with one of them. As you will see in the rest of this post, their approach starts with gathering a wide variety of stakeholders who are at least open to change, giving them the space to take a step back from the specific issues of the moment, and helping them envision alternatives to the current reality.

In fact, the Reos team will be the first to acknowledge that there is no guarantee that the practices they recommend will get always get you “from here to there.” Nonetheless, I am convinced that approaches like theirs makes it more likely that we will end up with what they call generative or creative solutions to the problems we face.

Choosing Collaboration in 2020

Perhaps the thing I like the most about Reos and Kahane is their commitment to collaborative problem solving especially if you want to bring about the kind of large scale social, political, economic, and environmental change I have spent my career advocating. Critics of cooperative problem solving, peacebuilding, and reconciliation often argue that we stress pay more attention to how we should go about solving problems than we too the substantive issues themselves. That’s especially true when we use terms like collaboration which often conveys images of French citizens and officials at least tacitly abetting the Nazis.

Kahane, of course, uses the other meaning of the term which overlaps with cooperation. But he does believe—and I agree—that we do have to work with people we disagree with and may not even like if we want to find transformative solutions to the kinds of problems we face today. If he’s right, what he calls stretch collaboration is our only viable choice.

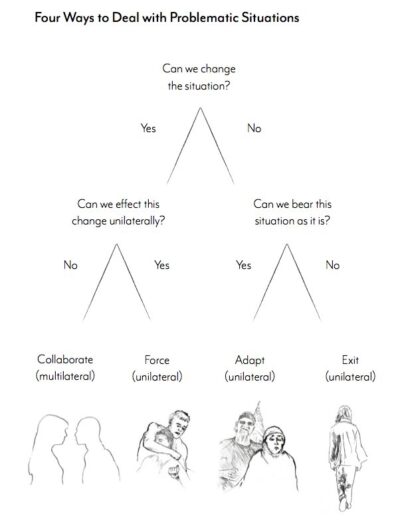

That’s the case because of what happens when Reos walks you through this decision tree. Admittedly, it oversimplifies things, but in a way that points us toward what Kahane stretch collaboration. We aren’t going to come close to solving our major problems—including race, climate change, economic inequality, and more—until and unless we find what social. Psychologists call the superordinate goals that allow us to identify common goals we can work toward together.

There are some critical choices involved, as reflected in this chart which they use in a lot of their presentations and Adam includes in his books.

First, you have to determine if you think you can do anything about the situation. If not, you can either acquiesce or flee.

If you decide that you can play a role in changing the situation, you have another choice to make as reflected in the left hand side of the diagram.

On the one hand, you can try to use force, which is not acceptable to most peacebuilders in any form, including psychological or economic coercion.

There may be intermediate forms, including the “force of argument,” which Reos leaves out or glosses over. However, their key contribution is getting us to see that a) we can’t not deal with most wicked problems, b) we can’t use force in our attempts to fix them, and c) that leaves us with only one alternative. Most of the problems we face today—including in post-Trump America—involve what psychologists call superordinate goals that in turn require some kind of cooperative solution.

As I’ve argued before, that means finding ways of working with people you disagree with. There are undoubtedly limits here. I’m not likely to be able to work effectively with the Proud Boys or QAnon activists.

Nonetheless, if Reos is right, there are plenty of people with whom I disagree profoundly but with whom I can also forge problem-solving, liberating relationships in my case, including plenty of people who voted for Donald Trump.

Balancing Power, Love, and Justice

I’m also drawn to Kahane’s approach because he doesn’t assume that we will ever agree on everything. to the contrary, his experience in places like South Africa during the troubled years between Nelson Mandela’s release and his becoming president suggests that it would be absurd to assume that adversaries will ever agree on some of the most basic issues dividing them.

As his thinking has evolved, Kahane has come up with ways to help people disagree but still find a way work together to take their country or community forward together. In my language, he helps them see superordinate goals that they all share and that can only be reached if the parties work together even if their intermediate goals remain different.

That involves a constant shuttling between three ways of working with each other which the next book will present from the facilitator’s point of view.

- In what he calls horizontal facilitation in which we help adversaries find a degree of common ground. It is, of course, what we peadebuilders turn to first and he, at times, has referred to as working with love for all.

- He contrasts that with the still-need vertical or hierarchical use of power in which we rely on traditional forms of leadership.

- In the new book, he adds the notion of justice which has been omnipresent in his work ever since he gave up designing scenarios for Royal Dutch/Shell and started using that form of planting to help social justice campaigns.

In his last three books, Kahane has increasingly argued that we change agents have to pick the tools that are most appropriate at the particular moment in time we find ourselves in. Like many of us who anchor or work in systems theory and complexity science, he realizes that we will have to be like sailboat captains who constantly shift their course as they take convoluted paths toward their destination.

Generating Shared Scenarios

Only now does it make sense to consider the tool Kahane and Reos are most famous for—scenario planning. Early in his career, Kahane ended up on Shell Oil’s famous scenario planning team whose work and the spinoffs it produced (including Reos) have helped countless companies get themselves unstuck.

Scenario planning remains at the heart of their work. However, it is seen less as an end in itself and more as a tool facilitators and other change agents can use in a distinctive way.

As I suggested last week, Reos has the participants in their extended workshops develop the scenarios themselves. In other words, they help design the futures they decided to work for and those they would rather avoid.

In other words, the value of scenario planning and related initiatives is that they make it a lot easier to envision what a dramatically different world or community could look like and plan accordingly.

Although I’ve spent a good deal of time with Kahane and other members of his team in recent weeks, we have not yet discussed how reconciliation fits into the mix from their perspective.

As I noted above, it is clear to me that the Reos tools can help people who have decided to take the long-term path toward reconciliation and that they may be needed in addressing the root causes of interactable conflict and other wicked problems.

Since I have to draft the article for the Burgesses and will be talking about reconciliation in the US with Adam and a few members of his team over the course of the next week, I expect to have clarified at least some of my own confusion by the end of the holiday weekend.

Tune in again then.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members

Also published on Medium.