I had my first two official introductions to Rotary’s peacebuilding work last week.

First, Gretchen and I attended the second of three planning sessions for a proposed permanent partnership between Rotary and George Mason University’s Jimmy and Rosalyn Carter School of Peace and Conflict Resolution. We will have plenty to say about it after the third meeting when some formal (and important) decisions will be made.

For now, it makes more sense to share my thoughts about the Rotary District 7610’s annual peace conference which we attended and helped lead because our Rotary E-Club of Global Peacebuilders is part of the region that includes much of Virginia.

A Rotary Primer, Take II

We did not know what to expect—other than the fact that we knew that this conference would be unlike anything we had ever done before.

We were blown away by what we experienced, but but before I get into that, it might make sense for readers who don’t know much about Rotary to expand a bit to the primer I wrote about its peacebuilding work shortly after we joined about a year ago.

Rotary is one of several service clubs that has historically attracted business and other community leaders who gather, as the slogan has it, to put “service above self.” Unlike some of the other organizations, Rotary has seven areas of focus of which peacebuilding is one. Its peacebuilding roots go back at least to World War II when it was one of the first NGOs to support the creation the United Nations.

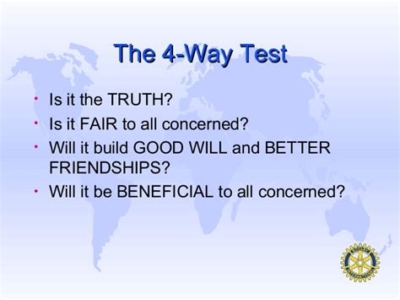

It also stands out from most other service clubs in its commitment to its Four-Way Test which Rotarians apply to every project they consider taking on:

Is it the truth?

Is it fair to all concerned?

Will it build goodwill and better relationships?

Will it be beneficial to all concerned?

Rotary is also one the most decentralized organizations I know of. Local clubs determine which of the organization’s areas of focus it works on with next to no supervision from district, zone, or international leaders. Most clubs are based in a geographical community, although we joined one of the growing number of online clubs. All of them focus on a topic and are organizationally linked to the district they were created in even though their members come from anywhere and everywhere.

Rotary is also one the most decentralized organizations I know of. Local clubs determine which of the organization’s areas of focus it works on with next to no supervision from district, zone, or international leaders. Most clubs are based in a geographical community, although we joined one of the growing number of online clubs. All of them focus on a topic and are organizationally linked to the district they were created in even though their members come from anywhere and everywhere.

We had initially joined an online club based in California which meant that its meetings started at 10 PM eastern time, which is way past my normal bedtime. So, the minute we learned that there was one based on the east coast whose Zoom sessions started at 7, we immediately transferred our membership.

Each district like ours has an annual conference. For the last two years, ours has added a second day for a peace conference which our club organizes. So, not knowing what to expect, with more than a bit of uncertainty we headed off to our first public Rotary meeting at which I would be giving my first Rotary presentation.

Not Your Usual Setting

Everything about the conference was out of the ordinary for me. It was at a country club in a small town on the Northern Neck of Virginia. Its rituals were not those that I’m used to from a lifetime spent at peacebuilding and political science meetings. We began with the Pledge of Allegiance. There was a sergeant at arms. The flow of the day was interrupted by raffles and door prizes. Many attendees wore Rotary shirts and hats and all manner of Rotary lapel pins. Most of the seven other people at my table had spent at least twenty years as Rotarians.

Not Your Usual Suspects

As we expected, we didn’t know anyone in the room other than the members of our club, and we hadn’t met a couple of them in person before.

As is the case with Rotary, the group was disproportionally white and older. Most attendees were middle class professionals. Not surprisingly given where our clubs are located, more than a handful of members had retired after careers in the military, although we were surprised by the number of veterans who chose to come to a conference dedicated to peace.

We were surprised, too, by the fact that more than ten percent of the attendees weren’t white and that women held most of the leadership roles—in an organization that only admitted women as members in the late 1980s. We were delighted, too, with how well-informed the attendees were about Rotary’s role in peacebuilding and of the field in general.

Nor Your Usual Reaction

Our club put together a program for an audience that didn’t know much about peacebuilding, . That’s why the club decided to focus our day on the phrase “peace is a verb” and on things that Rotarians could do to implement the eight pillars of positive peace in their daily lives, which was a no-brainer given Rotary’s partnership with the Institute for Economics and Peace which first developed that idea almost a decade ago. For readers not familiar with the pillars, they lay out eight characteristics of peaceful societies such as good relations with neighbors, functioning communications systems, a prosperous economy with a reasonably equal distribution of resources, and more. Most important for our purposes, the pillars are defined in a way that anyone can contribute to them during the course of their daily activities, whether they seem themselves as peacebuilders or not.

We started with a presentation by Al Jubitz who is the unquestioned leader of Rotary’s peacebuilding efforts in the United States. We asked him to talk about that history, Rotary’s use of the pillars of positive peace, and his own involvement in a city-wide, Rotary-led initiative on racial healing in Portland OR. Next we had Pamela Struss, a local mediator and adjunct professor at GMU’s Carter School discuss how she used personal mindsets or intellectual lenses in her work. We had planned to have GMU professor Arthur Romano next describe his work as a Rotary Peace Fellow twenty years ago and how it led to his current work on nonviolence education in American inner cities. Unfortunately, Arthur had to go later than planned, so we moved my final session ahead of his in which we asked the participants at each table to explore how they could apply one of the eight pillars of positive peace to the work they do in the daily lives and in their work as Rotarians.

On one level, the questions the participants posed and the discussions they led to were not all that different from those I get when I give talks to college students and other young people who have limited experience in peace and conflict resolution. On another level, the discussion was very different. The men and women who came to the conference were all experienced community leaders, including the younger members of the audience. That meant that they were able to see general ways they could work in their communities, especially in connecting the particular pillar their table had worked on with the Four-Way Test.

In short, while I had hoped that each table would come up with a reasonably concrete idea of what its members could do after they returned home, we fell a bit short of that goal. I was pleased that the group did connect the Four-Way Test to peacebuilding work, it probably was asking too much of a group to get to concrete ideas at a one-day event led by people they really didn’t know, two of whom only appeared via Zoom.

In any event, the conference ended in an unexpected way that made all of my concerns about not getting far enough evaporate. As is apparently usually the case at Rotary events, we had asked a district leader to close the event.

In this case, a woman about my age got up and rather than give some humdrum closing remarks, stole the show. The woman (whom I’ve chosen not to name for reasons that will become obvious before this paragraph is over) said she hadn’t thought much about peace until she realized that she has to do peacebuilding work in her daily life. It turns out that one of her daughters married an African-American man which means that she has had to have “the talk” with her grandsons about what to do when they are stopped by the police. As she said, that was not something she ever expected to have to do when she grew up in the white suburbs of Chicago or moved to Virginia to start her family. You could feel the air get sucked out of the room. Then, she explained how her former husband refused to have anything to do with his black grandchildren. You could feel the air get sucked out of the room again. Then, she put pictures of her biracial eight-month-old great grandchildren on the screen. You could feel the air get sucked out of the room again, but this time it was filled with positive emotions.

Not Your Usual Potential

In short, we came away from he day convinced that Rotary really can be a breakthrough force in American peacebuilding because its members truly aren’t among the usual suspects. That said, Al Jubitz is right when he says that Rotary underperforms on peace because it hasn’t yet found ways of engaging its members in that part of the work as effectively as it does in fighting polio or raising money to help victims of the war in Ukraine or any of its high profile concerns

But I could see ways of getting there.

What Comes Next?

Now, I also have to figure out how Gretchen and I fit into Rotary going forward. In particular, can we become more active in Rotary but limit ourselves to its peacebuilding work? As the cliché would have it, only time will tell.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.