World Peace and Other Fourth Grade Achievements

As election day and all the uncertainty that comes with it neared, I agonized over what to write about this. I didn’t want to add to the worries so many of us have about the outcome, but I had a hard time coming up with anything hopeful. to write about

To my delight—as well as to my surprise—I found the answer in an unexpected place where I had been spending a lot of time these days, which got me thinking in creative and enjoyable ways.

The View From a (Virtual) Fourth Grade Classroom

I haven’t been writing as many blog posts as usual this fall in large part because I have been sitting in on my grandson’s fourth grade classes. As is the case in much of the country, Fairfax County (VA) decided to hold all of its classes online this fall. Because Kiril is a typical fourth grader whose mind tends to wander, his parents asked me to help him stay focused on his assignments while my wife helps our granddaughter navigate first grade. Meanwhile, my step-daughter and her husband work from their home offices.

It has been an interesting semester so far. As you’ll see at the end of this post, his fourth grade experience is very different from mine in 1956. I mostly remember being bored and spending lots of time looking out the windows of Harbor School in New London CT and watching nuclear submarines being built across the river in Groton.

It has been an interesting semester so far. As you’ll see at the end of this post, his fourth grade experience is very different from mine in 1956. I mostly remember being bored and spending lots of time looking out the windows of Harbor School in New London CT and watching nuclear submarines being built across the river in Groton.

Kiril and his classmates are being challenged in ways we weren’t back then. And, despite all the problems associated with virtual learning in a pandemic, I’ve been overwhelmed by how good a job his teachers and classmates are doing.

In short, because I’ve been fascinated by the pedagogical dilemmas Kiril and his teachers face, it took me six weeks of sitting in his virtual classroom to recall a startling and relevant lesson I learned a few years ago.

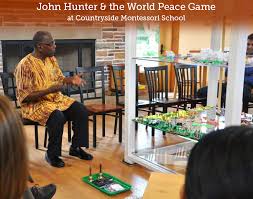

Enter John Hunter

I was listening to a C-SPAN interview with John Hunter while I was falling asleep one night in 2013. I’d never heard of him before, but, this soft spoken teacher suddenly grabbed my attention when he started talking about the World Peace Game which, apparently, he had been playing with his fourth and fifth grade students at schools in the Richmond and Charlottesville VA areas for over thirty years. As I heard him speak, any chance of falling asleep that night disappeared. After the show ended, I immediately got his book, World Peace and Other Fourth Grade Achievements, on my Kindle and read it in one sitting. It was also one of the first books I reviewed when I launched my web site.

I was listening to a C-SPAN interview with John Hunter while I was falling asleep one night in 2013. I’d never heard of him before, but, this soft spoken teacher suddenly grabbed my attention when he started talking about the World Peace Game which, apparently, he had been playing with his fourth and fifth grade students at schools in the Richmond and Charlottesville VA areas for over thirty years. As I heard him speak, any chance of falling asleep that night disappeared. After the show ended, I immediately got his book, World Peace and Other Fourth Grade Achievements, on my Kindle and read it in one sitting. It was also one of the first books I reviewed when I launched my web site.

The World Peace Game offers more than a feel-good story. The lessons extend beyond simulations that take place in fourth grade classrooms to all of us, especially as we face the uncertainties of America’s post-election future.

As I describe the game, you won’t have any trouble understanding why it had such an impact on me. You’ll also see that it is hard to describe because of its complexity and because it somehow seems to bring out the best in groups of fourth graders which my first grade granddaughter would undoubtedly describe as magic.

As the picture at the top of this post shows, the game’s centerpiece is a plexiglass tower with four layers, one each for the earth’s land and oceans, its subsurface, the sky, and outer space (where the weather goddess lives—more on that later). The land is divided into four countries of varying sizes and with varying assets on which the facilitator arrays a series of toy soldiers, weapons, oil wells, and other assets. Most students are assigned to one of the countries as either prime minister or another cabinet member. The rest of them are assigned to the World Bank, the United Nations, and a rogue band of arms dealers. A couple of students get to play another secret role, including that of the saboteur, who can wreak havoc, and the weather goddess, who can shake things up more or less at will.

The facilitator starts the game by giving the students an interconnected set of fifty global challenges and a set of rules for solving them. If you’ve read any of my recent posts, these problems have a lot in common with what I (and many others) call wicked problems whose causes and consequences are so inextricably intertwined that you can’t solve them quickly, easily, or separately, if at all. Meanwhile, the facilitator, saboteur, and weather goddess can shake things up.

The game itself is usually played over the course of eight weekly sessions in which the student teams make statements, threaten and negotiate with each other, and accumulate wealth and debt. They can even attempt coups and start wars. Meanwhile, Hunter, the saboteur, and the Weather Goddess complicate matters even further by adding new problems and crises.

The class is declared a winner if each “country” is better off and serious progress has been made on those fifty problems by the end of the term. The problem is that Hunter designed the game so that the students might well fail—just like us adults. If the problems themselves weren’t serious enough, he can always draw on the weather goddess and the saboteur (who is often the class troublemaker in real life) can thicken the plot.

Yet somehow, the kids always find a way to pull it all together. Almost always at the last minute. B

They succeed because they figure out a key lesson that Hunter himself has learned in his years of Buddhist practice. If the kids continue playing against each other, they will lose. If, however, they play against the game and its problems and do so by demonstrating genuine compassion, something clicks. They children enter what the social psychologists Mihály Csíkszentmihályi calls a state of flow. In sports jargon, the game “slows down.” The kids start cooperating with each other. They cut deals, and. eventually. they win because everyone is better off.

With a Side Visit from Robert Fulghum

It’s not just fourth graders. In the 1990s, the Unitarian minister, Robert Fulghum, had a runaway best seller with Everything I needed to Know I Learned in Kindergarten. Its title essay recounted the things he remembered learning when he was five and ended with these (then) famous words.

Take any of those items and extrapolate it into sophisticated adult terms and apply it to your family life or your work or your government or your world and it holds true and clear and firm. Think what a better world it would be if the whole world had cookies and milk about three o’clock every afternoon and then lay down with our blankies for a nap. Or if all governments had a basic policy to always put thing back where they found them and to clean up their own mess. And it is still true, no matter how old you are when you go out into the world, it is best to hold hands and stick together.

And Tom Lehrer’s New Math—Only a Child Can Do It?

Over the last few weeks, I have often found myself thinking back to my own elementary school days.

During the fall of my fifth grade year, the Soviets (remember them?) launched Sputnik, the first satellite, into space. Shocked American adults drew lots of lessons from our “failure” to “win” the “space race,” one of which was that we were doing a lousy job of teaching what we would today call STEM subjects in our schools.

That ushered in revolutions in the way American kids learned math, including the use of place numbers. By that time, I was already in junior high where we smart kids were taught algebra two years earlier than our peers.

So, when the humorist (who was also a political scientist and statistics professor), Tom Lehrer, wrote this song when I was in college, it struck home because I didn’t know much about either place numbers or base ten despite the fact that I had planned to major in math!

So, when the humorist (who was also a political scientist and statistics professor), Tom Lehrer, wrote this song when I was in college, it struck home because I didn’t know much about either place numbers or base ten despite the fact that I had planned to major in math!

Not surprisingly, when Kiril was reviewing place numbers which he learned in the second grade, my ears perked up and I remembered Lehrer’s song which seems doubly relevant today, especially its refrain.

Hooray for new math,

New-hoo-hoo-math,

It won’t do you a bit of good to review math.

It’s so simple,

So very simple,

That only a child can do itNow that actually is not the answer that I had in mind, because the book that I

got this problem out of wants you to do it in base eight. But don’t panic. Base eight is just like base ten really – if you’re missing two fingers.

Today’s math doesn’t require the hours of memorizing addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division tables and rules I had to spend. My first grade daughter even has an app on her iPad that is introducing her to the rudiments of algebra. No waiting for the seventh or ninth grade for her!

More importantly, like Hunter and Fulghum, Lehrer wanted us to see that we adults aren’t always as smart as we seem to be. My generation has done a rather lousy job in the sixty-three years since I sat (bored) in Harbor School.

And that leads me to my final point.

Why Should You Care About Fourth Graders

So, maybe if Kiril and Mila’s generation learn the lessons from these three old guys (Hunter is the “kid” of the group and is in his sixties; Lehrer is in his nineties), we might actually get somewhere.

I’m cautiously optimistic because of what their wonderful—and younger—teachers are doing in their classes. All of them foster an atmosphere of cooperation and compassion in their virtual classrooms. Kiril was introduced to the impact of bullying and the power of buddy benches in the second grade. Indeed, the first time he intellectually one-upped me came the day I came home and told him that I had just learned about these really cool things called buddy benches, and he told me that he and his classmates already knew about them.

I’m cautiously optimistic because of what their wonderful—and younger—teachers are doing in their classes. All of them foster an atmosphere of cooperation and compassion in their virtual classrooms. Kiril was introduced to the impact of bullying and the power of buddy benches in the second grade. Indeed, the first time he intellectually one-upped me came the day I came home and told him that I had just learned about these really cool things called buddy benches, and he told me that he and his classmates already knew about them.

This year, I’ve seen his teachers include civility as well as avoiding trolls when discussing proper online behavior. I’ve seen them discuss issues like climate change because they know their students are already worried about it. The teachers, too, know that the kids are having trouble dealing with a world in which they can’t see their friends without social distancing and wearing a mask.

Perhaps most importantly of all, they have assigned readings on the history of the civil rights movement and why we might not want to celebrate Columbus Day as such. That’s all the more remarkable given the fact that we are in Virginia where the school system they attend was segregated as recently as the 1960s.

Their teachers almost certainly won’t have them play the World Peace Game. It takes a lot of time to play, and teachers who lead it need a good bit of training.

Nonetheless, because they are doing a good job with the curriculum they have, it has been a fascinating and uplifting fall.

I just wish their parents would buy me a more comfortable chair, since it looks like I’ll be in fourth grade for the rest of the year, and who knows what will happen next fall when fifth grade begins.

Next Time

I published this post on November 2, the day before the final day of voting in the 2020 presidential election. I have no idea what will happen. At the polls. Or in the courts. Or in the streets.

Needless to say, I’m worried about what comes next here in the United States.

Needless to say, too, I will use the next series of posts to explore what we should do after the election, whoever wins.

I just have no idea what the next post will cover.

Stay tuned.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.

Also published on Medium.