This week, the first students will begin using the tenth edition of Comparative Politics: Domestic Responses to Global Challenges while I put the finishing touches on my web site and begin writing a comparable text for my other field which is tentatively titled, From Conflict Resolution to Peacebuilding. Not surprisingly, I have been thinking a lot about how the two fields overlap, but mostly about the ways in which they have little in common.

This week, the first students will begin using the tenth edition of Comparative Politics: Domestic Responses to Global Challenges while I put the finishing touches on my web site and begin writing a comparable text for my other field which is tentatively titled, From Conflict Resolution to Peacebuilding. Not surprisingly, I have been thinking a lot about how the two fields overlap, but mostly about the ways in which they have little in common.

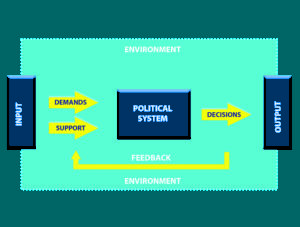

Until recently, I’ve worried more about the gaps in what my colleagues in peace studies know about current trends in political science. Here, however, I want to focus on the implications of the one thing we peacebuilders focus on that comparativists often ignore—the role of systems.

Ironically, comparative politics researchers got there first, which I learned in my first course in 1966. For someone coming from math, physics, and engineering, the writing of David Easton and Karl Deutsch grabbed my attention and kept it to the point that I have based my textbook on systems approaches from the beginning.

Ironically, comparative politics researchers got there first, which I learned in my first course in 1966. For someone coming from math, physics, and engineering, the writing of David Easton and Karl Deutsch grabbed my attention and kept it to the point that I have based my textbook on systems approaches from the beginning.

For good or ill, systems theory fell out of favor in political science at a time when it was becoming more important and more useful in dozens of other disciplines, including peace and conflict studies, although I have to say that colleagues in the hard sciences and management have made a lot more progress. In particularly, the more consistent use of systems-like approaches could help comparative politics in at least the following ways as I have seen both in my own classrooms and in reactions to my book.

- Systems mapping. We routinely draw and then keep improving visual “maps” that show how the components of a system are interconnected. That helps us see how its components connect to each other in webs of various degrees of complexity that take us beyond the simple snapshot implied in the version I use in my book.

- There are other models one can use in an introductory textbook or course. I’m drawn to systems theory because it focuses our attention on feedback and the ways what someone does today continues to have an impact in the future—and how the past has influenced the present.

- From Second to Nth Order Effects. Taken together, maps and feedback help us see that we can’t understand the world by examining the immediate impact of our actions. Rather, as this more typical systems map suggests, what “I” do today ripples out and directly or indirectly affects everything and everyone else in “my” system.

- System dynamics. Systems theory also helps draw our attention to the way countries or whatever unit we study changes over time. Most of the other popular models are great at giving us the equivalent of mental “snapshots” of a system’s component parts. Modern systems theory as used in other disciplines helps us turn those snapshots into the intellectual versions of videos—and extended play ones at that. And, it helps us see that a few systems are stable while some deteriorate and yet others perform better over time.

- Wicked problems. By honing in on interconnections among a system’s component parts, systems theory also gets us to focus on what planners and designers call wicked problems, gnarly intertwined issues whose causes and consequences are so inextricably intertwined that they cannot be solved separately, quickly, or easily—if they can be solved at all. Frankly, most of the problems that make so many of us want to tear our political hair out fall into this category. For good or ill, traditional comparative politics doesn’t help us get at wicked problems very well.

- This last point is not as obvious. However, my experience is that systems approaches help us deal with what I call domestic responses to global challenges better than most other models. To be sure, even systems analysis tends to lump global forces into what its creators called the environment. Nonetheless, it

Systems analysis is no panacea. It is a hard tool to use in doing actual research because the methodological tools it depends on require a lot more mathematical and computing skills than most social scientists have.

Nonetheless, I am convinced that systems approaches are helpful enough that I will be spinning these and other points out into a short primer on comparative politics before the end of January, which will appear on that part of my web site.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.

Also published on Medium.