Infinite Games

Because of my job as Senior Fellow for Innovation at the Alliance for Peacebuilding, I read a lot of books from outside of our field so that I can help my colleagues learn about ideas that they would not normally encounter in their everyday work. A few years ago, I started reading about infinite games and knew they were important for our work. However, it was only when I read Simon Sinek’s new book, The Infinite Game, that its relevance for peacebuilding and conflict transformation became clear to me.

Let me be blunt.

If we don’t think of peacebuilding as an infinite game, we will limit the progress we could conceivably make, whichever part of the field you happen to care the most about.

Finite and Infinite Games in a World of Wicked Problems

Game theory is a big deal in the social and natural sciences these days. Peacebuilders, for example, undoubtedly, encounter the prisoner’s dilemma early in their educational careers. Other games are central to modern economics, psychology, strategic studies and more.

There is only one problem. Most of the games we study (or teach) are finite games. They have an end point. They have winners and losers. They lend themselves to the kind of conflict resolution we learn about in books like Getting to Yes.

Unfortunately (or fortunately), most of the problems that we face today don’t lend themselves to finite games, no matter how sophisticated. And, there are lots of sophisticated finite games out there, which I won’t bore you with here.

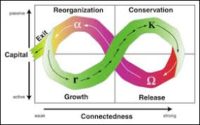

I can ignore them here because they aren’t terribly good at helping us understand the kinds of wicked problems we peacebuilders face and that I keep harping on whose causes and consequences are so inextricably intertwined that the can’t be solved quickly, easily, or separately–if they can be solved at all. As Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber who coined the term forty years ago argued, there is no ending point in dealing with a wicked problem. There is neither a win/lose or a win/win outcome that settles everything once and for all.

That’s what most peacebuilding issues. A system or society can become more peaceful or less peaceful, but we’ll never get to peace itself unless we somehow reach some unreachable utopia. As I also keep harping about, conflict is a fact of life and always will be. We might reach win/win outcomes on some aspects of complex issues, but only on some aspects. There will still be plenty of conflict left to deal with.

Peacebuilding and conflict transformation, therefore, are best treated by thinking in terms of infinite games that have no end point and that keep on going forever—or at least for our entire lifetime and beyond.

They have known and unknown players. Rules change on the fly. Patterns emerge and shift like a kaledescope. You can win round after round and end up losing the whole thing if, as is rarely the case, the game ends up at an ending point.

Sound familiar?

Sinek’s Model

Simon Sinek wrote his book with business leaders in mind. However, his five rubrics make sense for those of us who are, in the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, trying to “create a more just a peaceful world.”

- Just cause. This flows straight from the MacArthur Foundation’s tag line and is the easiest for us to live up to. World peace is, of course, a justifiable goal. However, thinking in terms of infinite games suggests that what we mean by that and how we get there will change over time. As we have moved through three more or less distinct phases in the last thirty years, we seem to be moving into a fourth in which we have to build broader coalitions than we ever have before. That may not mean rethinking our cause at the most basic level (e.g. nonviolence), but it does mean reconsidering some of its specifics, most notably the partners we choose to work with along the way.

- Learn from your “worthy rivals.” Of Sinek’s suggestions, this is the one that hits closest to home. Sinek spends a good bit of time talking about the fears he once had in dealing with someone he thought was his biggest rival. In the end, he (Sinek) found it paralyzed him or at least kept him from living up to his potential. Then, he had to share a stage with his supposed rival and discovered that their skills complemented each other. He and Adam Grant (also one of my favorites) have since become colleagues and friends as you can see in this video of theirs from the 2017 Aspen Festival. Each of them does better work as a result. I know I don’t learn as much as I could from the people I disagree with because I fear they are trying to steal my thunder. In short, it’s time to learn my own lesson. I’ve written about this some recently when I’ve dealt with empathy. But, I suspect there’s a lot more to deal with here.

- Trusting teams. This, too, seems to be all but obvious. However, it is not always clear to me that we build trusting teams across organizations. I like the way just about all all of the AfP member organizations do their work. We were create, however, in part to help them work together We’ve made some progress along those lines in the fifteen years I’ve been associated with AfP, but we could do a lot more. Especially as our field grows, we could learn a lot from companies that gone to scale and kept their core mission and goals intact. Sinek and Grant talk a lot about managers that treat the people they work with well, especially on their worst days. Grant, in particular, talks about finding common ground through finding what he calls “uncommon commonalities.” I wonder how often we sit down with people we disagree with and start by finding the unexpected things we just might have in common.

- Be flexible. This is also something we sometimes honor in the breach. On one level, we know that our strategies and tactics have to change along with the times. However, I’ve seen us struggle to do be flexible, first in responding to the changed environment after 9/11 and, now, in trying to create a movement or movements that could change popular culture and public policy when it comes to conflict related issues.

- Display the courage to lead. Here, too, this is a lesson I have to learn. One friend of mine recently said to me, “Chip, the world needs peacebuilders now more than ever” given the geopolitical circumstances we have to cope with. However, courage is not always easy to summon up. I keep asking myself, “who am I to try to be a thought leader?” Or any kind of leader. Yet, the very logic of systems theory upon which all of my work is based suggests that we are all leaders whether we want to be or not, at least in the microcosms of our daily lives.

Why Infinite Games Matter

The bottom line is simple. If we don’t begin to see our work as a kind of infinite game, we are not likely to see our impact be taken to scale. We will, in other words, continue to be marginal players in a world that needs us to maximize our influence over both popular culture and public policy.

Thinking in terms of infinite games girds us to both take for granted the idea that we are in this for the long hand and that everything we do—from the ways we lead to the ways we run our personal lives—will have to adapt to changing circumstances.

On one level, that can be scary.

On a more important level, it can also be lots of fun.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.

Also published on Medium.