Democracy in America

I don’t put on my comparative politics hat very often now that peacebuilding and related issues have taken over my professional life. But, given the threats to democracy in the so-called advanced industrialized democracies that I wrote and taught about the most, I constantly find myself trying to build bridges between the two halves of my professional life now that peacebuilders have to confront conflicts in their own backyard that call on me to use what I know as a political scientist.

It isn’t hard to see why. In countries as different as Hungary or the United Kingdom or the United States, democracies are facing unprecedented dangers that could undermine what seemed like stable regimes just a handful of years ago. When and if those democracies weaken even further, their deterioration could unleash the kinds of violent conflicts my colleagues have spent the last few decades working on in Latin America, Africa, and Asia.

It isn’t hard to see why. In countries as different as Hungary or the United Kingdom or the United States, democracies are facing unprecedented dangers that could undermine what seemed like stable regimes just a handful of years ago. When and if those democracies weaken even further, their deterioration could unleash the kinds of violent conflicts my colleagues have spent the last few decades working on in Latin America, Africa, and Asia.

I had the opportunity to blend comparative politics with peacebuilding once again last week when I attended three events that addressed the threats facing democracy in the United States. The first was a discussion of Alexander Hinton’s new book, It Can Happen Here (which I’ve reviewed elsewhere). It was followed by two webinars on dangerous speech organized by my colleagues at the Alliance for Peacebuilding and the TRUST Network.

As often happens after such events, I found myself in an intellectual quandary. On the one hand, the conclusions my colleagues reach leave me even more worried than I was in the aftermath of the January 6 insurrection. On the other, I can begin to see some ways out of the dilemma we find ourselves in although I’m by no means convinced that we will take any of them.

It will take me four steps to get there.

Threats on Three Levels

Whenever I go to sessions like these, I find myself revisiting one of the memes I relied on the most when I wrote and taught about comparative politics. Some of the pioneers of modern, behavioral approaches to the study of comparative politics pointed out that we should think in terms of political life in any country as operating at three levels:

- The government and issues of the day

- The overall regime or the set of rules and cultural norms that persist from government to government more or less unchanged over time

- The existence of the system itself as a single entity

For most of my career, I could safely make the case that protest in Western Europe and the United States had rarely gotten “above” the level of the government of the day since the end of World War II. Indeed, I could make the case that anyone in the most stable democracies like the United States or United Kingdom who talked about regime change would not be taken seriously. Or worse.

To convince my students that i was right, I only had to point an analytical finger at myself.

Some of us in the protest movements like ones I was part of and wrote about in the late 1960s and early 1970s certainly would have loved to challenge at least a few of the core public policies and/or cultural norms that shaped our lives, but we ended up shooting ourselves in the clichéd foot whenever we did so, because average citizens were not prepared to go that far however angry they might have been about segregation or Vietnam or Richard Nixon or Charles de Gaulle.

But now, I can’t say that any longer. The differences between the three levels are blurring faster than they have been at any point in my professional lifetime. More and more people are questioning the value of both the rules of the game and of the values that have supported them for decades.

The irony, of course, is that many of those protesters make their demands in terms of supporting the constitution or restoring American (or British or French or Hungarian) values. The fact is, however, that millions of people have begun crossing what always struck me as an uncrossable line between opposition to what the government of the day is doing to opposition to many of the basic principles on which our governing system is based.

I don’t need to go into those threats in any detail here, because you wouldn’t be reading these words if you weren’t already aware of them. Thousands of people have already taken part in insurrectional activities. For the first time in decades, office holders are in the process of passing legislation that will make it harder for people to vote and exercise other basic rights that we took for granted not so long ago. Some polls suggest that as many as seventy percent of Republican voters think that Joseph Biden is not the legitimately elected president of the United States.

In some other countries, even the system itself is under assault. The UK left the European Union and separatist movements are gaining strength in Scotland and Wales. Even the handful of people who think Texas should succeed are no longer considered crackpots.

I suspect that I’m less worried than Hinton is that democracy could collapse and something akin to genocide could happen here. Nonetheless, the signs that something along those lines could at least be possible are growing.

Still, I find it hard not to agree with Liz Chaney’s words in an op-ed in the Washington Post last Thursday.

The Republican Party is at a turning point, and Republicans must decide whether we are going to choose truth and fidelity to the Constitution. In the immediate wake of the violence of Jan. 6, almost all of us knew the gravity and the cause of what had just happened — we had witnessed it firsthand.

And, of course, I find it hard to believe that I’m actually agreeing with Liz Chaney on anything given her family’s political role over my adult life time.

Thinking Like a Comparative Peacebuilder

The three levels only take us so far. While they do help us see that things are getting worse, they are of less use when it comes to figuring out what to do about a situation that is clearly deteriorating—even if it hasn’t (yet) reached the depths that Hinton worries about.

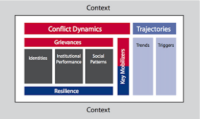

To do that, we need the kinds of analytical tools I’ve learned about in my second career as a peacebuilder. Here, consider the conflict analysis framework developed by the United States Agency for International Development. Like the political scientists’ three levels, its categories do blend into each other, but the framework does point us to three issues whose importance we tend to underestimate even though they produce the conditions that make events like the January uprising and the like possible.

- Social conditions like today’s economic and demographic shifts that help give rise to the conflicts that afflict societies like our own.

- Grievances that go beyond the issues of the day and that can eventually erode support for the regime if not the existence of the country as a whole.

- Institutional performance or the lack thereof, especially the national government’s perceived inability to address either the changing social conditions or meet the grievances.

It is in that context that recent research on so-called dangerous speech and on the people who took part in the insurrection makes the most sense.

Evidence that Americans have qualms about their government and its ability to solve pressing social problems has been mounting for decades. The Dangerous Speech project, for example, has explored the spread of narratives that dehumanize opponents, reinforce our division of the world into ingroups and outgroups, and the like. Similarly, Robert Pape leads a research team at the University of Chicago that has shown that the people arrested after the January 6 insurrection disproportionately came from swing districts that are undergoing dramatical social and demographic change.

On the right, all of this reached new heights (or, should I have said new depths) amid the Trump team’s failure to address the pandemic or any of the lingering social problems all the while casting the blame for what happens on immigrants, the deep state, radical socialists, and immigrants among others. Smaller and more socially isolated groups harboring similar levels of anger and frustration exist on the left as well, although we know that networks like Antifa are tiny despite the fulminations coming from Trump and his allies.

On the right, all of this reached new heights (or, should I have said new depths) amid the Trump team’s failure to address the pandemic or any of the lingering social problems all the while casting the blame for what happens on immigrants, the deep state, radical socialists, and immigrants among others. Smaller and more socially isolated groups harboring similar levels of anger and frustration exist on the left as well, although we know that networks like Antifa are tiny despite the fulminations coming from Trump and his allies.

Under the circumstances, it doesn’t take much to “trigger” an outburst in USAID’s terms. To be sure, a lot of organizing by the likes of QAnon and the Oath Keepers lay behind what happened in Washington in January and in all of the other outbursts we’ve seen since the 2016 election. Nonetheless, it is hard to see claims of “stopping the steal” having the kind of galvanizing impact they did this year if we could somehow turn the clocks back a decade or so.

The fact that the recent protesters speak in terms of defending the constitution should not keep us from seeing that they are taking the first potshots at the American regime since the Civil War that have gained anything approaching traction in broad swathes of American society.

Why I’m Less Worried

If all you had to go on was what I’ve written so far, you could and should be very depressed. However, the distinction between the government of the day and the regimes, the USAID framework, and what I learned from last week’s speakers who had spent time in a variety of extremist movements all give me reasons for hope and pointed me toward things we peacebuilders could do.

None of what follows, however, will come to fruition quickly in a way that decisively ends the threat to American democracy because that simply can’t happen. There are no quick fixes. It took us a long time to dig the political hole we find ourselves in. It will also take years of hard work to pull ourselves out of it.

That’s the case largely because one of democracy’s bedrocks is being eroded—trust. A mountain of research has documented declining rates of trust in our institutions and in each other throughout my adult lifetime. Still, what I heard in those seminars and know as a political scientist and peacebuilder suggests three ways in which we could rebuild that trust and, with it, strengthen our democracy.

None of them may convince people who stormed the Capitol. That’s not the point. If your goal is to keep millions of disaffected Americans from reaching similar conclusions, these three action areas just might help.

Institutional Performance. This first one is obvious. The government has to do a better job of addressing the problems facing the country in ways that benefit (just about) everyone.

But as we al know, that is easier said than done. And given the difficulties we’ve experienced over the last few decades, it isn’t getting any easier.

To use USAID’s terminology, the people who have doubts about American democracy have real grievances,. They have good reason to believe that millions of Americans like themselves have not been treated fairly by a succession of Republican and Democratic governments over the last half century.

Here, the Biden administration may be off to a promising start. It has proposed policies that could eventually address the social and economic problems that gave rise to so many of the grievances being played out today.Some of the provisions already enacted and many in the pending legislation are explicitly aimed at working class and other voters whose interests have been ignored too often given the way global capitalism has evolved.

The administration clearly understands that it has to address issues as different as the impact of centuries of systemic racism and the grievances of white working class voters who feel that their livelihoods have been destroyed by globalization and the like. It is by no means clear that the proposed legislation will be enacted or that it will have the intended impact if is. Nonetheless, the 2020s mark the first time since the 1980s or perhaps the 1960s that anyone in power has proposed the kind of sweeping overhaul that could strengthen the American regime.

Building Bridges. As the speakers at last week’s events who have themselves spent years in extremist movements pointed out, those grievances have deep emotional roots, and public policies alone can’t and won’t address all of them. We also have to reach out to the people we disagree with in ways that are unfamiliar to most American activists but are also part of the peacebuilder’s stock and trade.

Like many of my friends, I am furious (to say the least) with the men and women who stormed the Capitol and, even more, with the political leaders who aided and abetted them.

But we peacebuilders know that demonizing and dehumanizing the people we disagree with will only make matters worse. To that end, a new generation of neuroscientists and other scholars have lent empirical support to a key conclusion which peacebuilders reached in the 1980s. If you want to permanently solve a problem, at some point you will have to build trust among the people who disagree with each other. That almost never happens when you call each other names like racist or radical socialist.

As British journalist Ian Leslie (among many others) points out in his new book Conflicted, people are most likely to change their minds and their behavior if they feel respected and listened to. That holds in any number of situations from hostage negotiations to political debates. As my friend Chad Ford puts it, it helps unblock any social or political or other emotional stalemate if we proactively take the first step and “turn toward” the people we disagree with.

As British journalist Ian Leslie (among many others) points out in his new book Conflicted, people are most likely to change their minds and their behavior if they feel respected and listened to. That holds in any number of situations from hostage negotiations to political debates. As my friend Chad Ford puts it, it helps unblock any social or political or other emotional stalemate if we proactively take the first step and “turn toward” the people we disagree with.

I’m not sure any of that would work with the kinds of people who occupied the Capitol or with their equivalents on the left. Still, there are millions of people who voted for Trump and angry protesters on the left who could end up becoming the kinds of activists who oppose not just our government’s policies but come to doubt its very legitimacy as well.

We peacebuilders have long advocated doing what the likes of Leslie or Ford advise while working with clients in conflict zones far from our own shores. I fear that we haven’t followed our own advice anywhere near well enough now that we are working in the United States. Unlike our efforts in Burundi or Bhutan, we have “skin in the game” when we get involved in disputes in Baltimore or Boise.

Put simply, we can’t be the impartial “third party neutrals” we were trained to be in our mediation classes. When the issues hit this close to home, we are called on to take a stand and be on the right side of history.

We can, however, become advocates who embody peacebuilding values in everything we do. As my friends at Build Up point out, one can be non-neutral and non-polarizing. We can respect the people we disagree with by opening conversations with one of Leslie’s lines. “I’d like you to help me understand” why you feel the way you do. In his terms, we have to start working with our adversaries—or anyone else for that matter—by taking them seriously whoever they are right now. If we set out to “right” the people we disagree with, we are more likely to deepen the divisions between us rather than find common ground.

Again, this is something we peacebuilders have learned from our work abroad.

Now, it’s time to apply those lessons to ourselves as we engage in America’s political debates.

Resilience. It is only at this point that we can realistically talk about the final key term in the USAID framework—resilience. As recently as the early 2010s when respected pundits began worrying about the challenges facing American democracy, it was easy to talk about the “guardrails” that protected American democracy, including the widespread confidence in our regime (if not the men and women in power at the moment), a political culture that revolved around the all but universal agreement that the regime is legitimate, American exceptionalism, and more.

Given the events of 2020 and 2021, it is hard to make the case that ours is a resilient system, if by that you mean that it has the capacity to bounce back from adversity. Few of us may be ready to throw out the constitutional system that has been in place for more than 230 years. But it should be clear that it is getting harder and harder for us to respond effectively when things seem to be going wrong.

In other words, our resilience has to be (re)built.

We peacebuilders don’t have enough influence over policy makers today to have a major impact on the legislation that is passed in Congress, the executive actions taken by the administration, or the decisions issued by the courts. We can, however, work on those aspects of resilience that involve average citizens in ways that are anchored in our accomplishments around the world in the years since the modern peacebuilding field was created in the 1980s.

If we have demonstrated anything, it’s that stable peace cannot be built solely from the top down. As recent research on local peacebuilding has shown, it is much easier to build a resilient system by starting at the grassroots level and helping people build peaceful, just, and equitable societies in their immediate environments. That means using the bridge building discussed in the previous section to (re)build effective institutions in the public and private sector that both bring us together and then allow us to solve specific problems.

There is no better example of this than our failure to come up with effective responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. While there will always be disagreements over specific policies we could and should have pursued, there should be little doubt that we have failed in our efforts to see the pandemic as a crisis that we all share and that we can only solve by working together.

In other words, a resilient society in the 2020s is one in which there is a widely shared agreement that we face a series of problems whose causes and consequences are so inextricably intertwined that we can’t solve them quickly, easily, or separately—if we can solve them at all. We can only be resilient and “bounce back” if we also understand that the issues of our increasingly interdependent world are such that our solutions have to take our reliance on each other as their starting point.

Next Steps

As I pointed out earlier, neither you nor I can do much to influence public policy making.

We can, however, be part of a variety of efforts to change community or cultural norms that, in turn, could do everything from rebuilding trust to strengthening democracy while moving the country in a progressive direction. All of it will take time. Some of it is not likely to fully bear fruit during my lifetime. However, I am convinced that we can make significant progress.

In addition to doing what I can as an activist, I am writing a book with a few of my young friends that documents what thousands of people in their generation are doing to combat systemic racism, reform police departments, create equality in all its forms for all Americans, end the threat of climate change, and become more self-aware human beings when it comes to defining our role in an increasingly interdependent world.

I’ll be writing that book, tentatively entitled Connecting the Dot, over the course of the next year or so and will document my progress (and the lack thereof) in future posts.

So, as the television announcers of my youth used to put it, stay tuned.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.

Also published on Medium.