Reconciliation 2020

This is the third in a series of posts on what we could and should do to “bring out the best in us” as we prepare for the Biden administration to take office.

It has also taken me a month to write, which is the longest gap between any two posts since I started writing my blog in 2018.

It took me that long in part because reconciliation is a tough topic and in part because I hadn’t planned to write about it when I began the series. However, a seemingly unrelated request from Guy and Heidi Burgess convinced me that I had to write about it now because the conflict and divisions in the United States are forcing reconciliation toward the top of our political agenda.

In 2003, they commissioned me to write an essay on reconciliation for the Beyond Intractability data base. In the seventeen years since then, they updated it by adding excerpts from other things I wrote as well as some ideas of their own. This fall, they decided that the original essay had become too convoluted and too dated. So, they asked me to rewrite the whole thing.

In 2003, they commissioned me to write an essay on reconciliation for the Beyond Intractability data base. In the seventeen years since then, they updated it by adding excerpts from other things I wrote as well as some ideas of their own. This fall, they decided that the original essay had become too convoluted and too dated. So, they asked me to rewrite the whole thing.

I thought it would be easy to do so. As you’ll see here, the basic principles I wrote about still hold. However, once I sat down to write, I realized that reconciliation and related ideas are now at or near the heart of what most peacebuilders do.

I ended up with a document that is far too long for either a blog post or an entry in the Beyond Intractability data base, because I wrote it so that it would fit in to the projects on reconciliation in the United States that I’m currently working on.

Bringing Out the Best in Us

In this first post, Defining the Best in Us, I explore the challenges we face in the aftermath of the 2o20 election.

Getting (politically) unstuck explores how peacebuilders can begin getting us out of the rut(s) we are in.

Here, I consider why reconciliation is so important today in the United States and beyond.

This post explores what we can do to meet the democratic crisis and improve life for us all.

Take on the Issues

Preventing Violence and Reducing Polarization

Beyond Dialogue for its Own Sake

Leverage Policy Makers

Where We Go from Here

Defining Reconciliation for the 2020s

Defining Reconciliation for the 2020s

Defining reconciliation is easier said than done as the word cloud I used to start this post suggests. At the very least, it includes all of those terms and lends itself to the inevitably confusion that comes when people use any terminology in a variety of ways as is certainly the case with reconciliation.

In practice, the idea behind reconciliation is actually quite simple if we take a brief detour from peace and conflict studies and consider some basic accounting principles. People of my generation at least should have done some reconciliating at least once a month when our banks sent us our monthly statement for our checking accounts. If we were good financial citizens, we made certain that our records matched the bank’s. Once we made certain that our figures agreed with the bank’s, we were said to be reconciling our accounts.

Financial reconciliation is, of course, a lot more complicated than I coiuld describe in a single paragraph. Still, both financial and political reconciliation have a similar goal—creating balance or harmony, whether in one’s financial or one’s social relationships.

Creating Harmony

The similarities between political and financial reconciliation grow out of the term’s etymological roots. “Conciliation” speaks to the creation of an agreement, while “re” refers to doing so again, a point I will return to in the next section.

From that perspective, reconciliation is more than just conflict resolution, if by that you mean more than reaching a win/win outcome or any such deal. To be reconciled, two parties have to reach something akin to closure and mutual satisfaction on whatever it was that divided them. And that rarely can happen with a single deal because the kinds of conflict we are interested in—like racism in the United States—are complicated issues that have been years (or longer) in the making and are embedded deeply into people’s value systems as well as their country’s public policies.

Thus, think of reconciliation as the end product that is only reached when a family or community or country has developed harmonious relationships—itself not exactly a precisely defined term! Major problems might not all be solved, but we would have made significant and irreversible progress toward solving them. More importantly, we would all feel confident that there was more progress to come and that we could continue on the journey toward solving them.

In such a society, people will still disagree because there will always be conflict. However, we have “conciliated” enough that those differences cannot take us to the brink of “war” at everything from the interpersonal to the international levels.

Degrees of Reconciliation

As my methodologist friends would put it, reconciliation is not a binary. You cannot say that one-time adversaries are ever fully reconciled. It makes more sense to think in terms of the degree to which the parties to a dispute are reconciled which could be measured by points on a continuum with a harmonious society that can settle its differences without resort to violence of any kind at its more hopeful end.

It evokes a world that is anchored on a version of the Golden Rule that exists in all of the world’s great spiritual and religious traditions. I treat you with dignity and respect, and you do the same to me. And that can happen only if we work through the issues that have divided us in both substantive and emotional terms.

Reconciliation is most needed in the most divided societies. Those of us who prioritize it in our work are drawn to the kinds of protracted conflicts that the Burgesses had in mind when they chose the word intractable in naming their project. They are hard to solve because the divisions that gave rise to them are deeply rooted and have been so for generations. These are the societies and communities who have experienced genocide and other traumas and where dehumanization and other social maladies have been taken to an extreme.

In sum, reconciliation leaves us with a paradox. The societies that need it the most are also those that need to change the most. Therefore, as you continue reading, remember that reconciliation cannot be achieved quickly or easily. Ironically, patience is needed in addressing problems in societies and communities in which patience is most likely to be in short supply.

For the 2020s

Like everyone else, I have struggled with the events of the last few decades which culminated in the overlapping crises of 2020. Like everyone else, too, I was tempted to find short term solutions to the problems we face. Yet, the crises also drove home my conclusion that we may not be able to solve any of them unless we take reconciliation seriously.

We won’t be able to solve them using reconciliation alone. However, ignoring it will at best allow us to make marginal gains and at worst perpetuate the problems themselves.

To see why, just consider one of them—race relations in the United States.

As events keep reminding us, racism remains what Gunnar and Alva Myrdahl called the American Dilemma eighty years ago. The centrality of race in American life is, of course, far older, stretching back at least to the initial “discovery,” settling, and consquest of the Americas.

We have made progress, especially during my lifetime which began shortly after the Myrdahls published their seminal book. However, there is still plenty of progress to be made as the recent discussion of and pushback against claims about systemic racism will attest.

If we want to make the kind of progress that could eventually end the pernicious impact of systemic racism, we will have to adopt public policies that address the economic, social, environmental, and other consequences of systemic racism, many of which have been on center stage in 2020. However, the public policies we adopt can only go so far unless and until the American people adopt cultural norms that embrace a deracialized United States. The problem is that progress toward the first goal sometimes makes it harder to reach the second one because even incremental public policies produce both resentment among the social groups who seem to be losing out and among their supposed beneficiaries who grow frustrated by the slow pace of change brought about, in part, by that very resentment.

That is where reconciliation comes into play. When done right, it allows a community or a society to overcome the emotional and other wounds that are an inevitable byproduct of systemic racism or any other deep social division. In the end, it is what makes progress toward dramatic and non-incremental public policy changes and their public acceptance possible.

As you are about to see, reconciliation takes us down a path that leads both to profound policy transformation and the adoption of profoundly new cultural norms. But, as we have also seen during the course of this troubling year, it is never easy to reach reconciliation because it requires touching the hearts and minds of millions of people. To stick with the example of racism, it’s not just the overtly racist practices and that attitudes that underlie them that have to change. We all do, including many of us who think that we are on “the right side of history.”

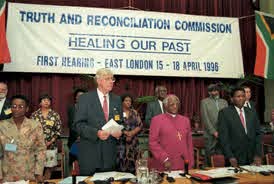

Even more importantly yet, reconciliation can only happen when people on all sides decide to talk with each other so that they can overcome the problems that divide them. No one has put this better than the most famous supporter of reconciliation in the world today, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who was co-Chair of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission in the 1990s.

Forgiving and being reconciled to our enemies or our loved ones is not about pretending that things are other than they are. It is not about patting one another on the back and turning a blind eye to the wrong. True reconciliation exposes the awfulness, the abuse, the hurt, the truth. It could even sometimes make things worse. It is a risky undertaking but in the end it is worthwhile, because in the end only an honest confrontation with reality can bring real healing. Superficial reconciliation can bring only superficial healing.

Despite what some critics might say, reconciliation does not involve running away from our divisions by working with what he justifiably calls our enemies. With them, we both have to come to grips with a traumatic past and its impact on the present. Both sides have to heal in ways that go far beyond putting a metaphorical band aid over a wound. In the language used by many of today’s activists, reconciliation has to take us beyond virtue signaling so that people on all sides make non-incremental progress toward solving deep historical divisions.

What that entails obviously depends on the circumstances of a given conflict and community, but it always includes a mix of public policies that directly address the situation on the ground and social-psychological programs that help people overcome trauma and the emotional costs of being in a conflict. Most reconciliation programs focus on the emotional aspects of conflict, although I will return to the policy side of the equation toward the end of this post.

Reconciliation and its Discontents

When I start presenting reconciliation in this way, my more cynical friends shriek in disbelief calling it pie-in-the-sky idealism. As you will see in the second half of this post, I agree with those skeptics in lots of ways.

Nonetheless, some of the critiques leveled against it miss the ways in which it is all-important, no matter how difficult it is to actually pull off. And, since some of them also make it hard to see what reconciliation itself really is, it makes sense to take the two most misleading ones on before I get beyond this most bare-boned definitions.

The Unfortunate “Re”

That starts with the two little letters that begin the word—re. As noted earlier, using them at the beginning of a word implies a return to something that existed before, which in this case would suggest a return to a more harmonious past.

The problem is that I can’t think of any real-world example in which peacebuilders would dream of proposing a return to some earlier era in which people already got along for one simple reason. No such period ever existed. You don’t need at PhD in conflict resolution or American history to know that the United States has never had anything resembling a “golden age” in race relations in the five centuries since Columbus landed in what he mistakenly thought of as a new world.

It’s not just the United States. The kinds of identity-based conflicts that are roiling so many parts of the world today, too, are centuries old. Many, for example, trace the hostilities between Serbs and Kosovars back to the Battle of Kosovo Polye—in 1389. In all of these cases, too, creating a society characterized by reconciliation would mean creating a society that has never existed before.

If we had it to do over again, we might not have chosen a word that begins with “re” and therefore seems to connote some kind of glorious and harmonious past in describing our work. Alas, we can’t do that, and we are stuck with a word which English speaking peacebuilders inherited from Christian theologians who talked about a believer’s need to reconcile him or herself with Jesus Christ and, therefore, with his or her fellow humans. Indeed, even in that wing of the Christian community, one’s spiritual reconciliation with God does not revolve around a return to some pre-existing ideas. Even that does not evoke a return to anything like a better and harmonious past.

However you define (at least outside of accounting), reconciliation rests on building a new future that is qualitatively different from anything that has existed in the past.

Beyond Kumbaya

Reconciliation comes with another unfortunate connotation. Skeptics conjure up images of people sitting around a campfire singing Kumbaya.

I find that image doubly worrisome. First, I was a camp counselor and music director at a YMCA camp in the late 1960s. We never used Kumbaya for those purposes, nor has any credible peacebuilder whom I’ve met ever since.

Second and far more importantly, the image misses the fact that reconciliation takes hard work to both reach and sustain. As Archbishop Desmond Tutu often said about the South African TRC (see the next section), reconciliation isn’t cozy. It doesn’t come quickly or easily. Indeed, achieving anything like reconciliation normally takes years or even decades. And, in a country like the United States whose racism is etched into its entire history, the first signs of reconciliation will also have to constantly reinforced and nurtured if we want the change to survive the challenges and setabacks we will inevitably encounter along the way.

In today’s terms, critics suggest that people who talk about reconciliation really don’t care about making major substantive changes. Instead, they do little more than perform symbolic acts that are all but meaningless, eliciting pejorative labels like performative or virtue signaling.

There is nothing new to those criticism. The 1960s satirical songwriter, Tom Lehrer, raised the alarm in his song, National Brotherhood Week.

Oh, the poor folks, hate the rich folks

And the rich folks hate the poor folks.

All of my folks hate all of your folks.

It’s American as apple pie.

But during…National Brotherhood Week

National Brotherhood Week

New Yorkers Love the Puerto Ricans ’cause it’s very chic

Stand up and shake the hand of

Someone you can’t stand

You can tolerate him if you try.Oh the Protestants hate the Catholics

And the Catholics hate the Protestants

And the Hindus hate the Muslims

And everybody hates the Jews, but duringNational Brotherhood Week

National Brotherhood Week its

National everyone smile at

One another-hood week, be

Nice to people who are

Inferior to you. it’s only for a week so have no fear

Be grateful that it doesn’t last all year

As you are about to see, when done well, reconciliation is a far cry from either virtue signaling or Lehrer’s National Brotherhood Week. Companies that make slick television ads but don’t change their internal hiring and promotion policies, for example, may meet Lehrer’s “standards,” but in can actually do more harm than good.

To be sure, reconciliation does require that “people take the hand of people you can’t stand” as Lehrer jokingly sang. However, as you are about to see, it involves a whole lot more than that and is a necessary—if not sufficient—precondition of the kind of lasting changes he and I envisioned then and still want to see happen today.

Lederach’s Contribution

Reconciliation entered contemporary peacebuilding primarily through the work of a single scholar practitioner. John Paul Lederach has spent his career working for reconciliation in much of the Global South and helped train other practitioners first at Eastern Mennonite University and later at the University of Notre Dame. In both roles, he earned the all but universal admiration of his colleagues around the world in part because he drew our attention to four key components of reconciliation. Although Lederach’s own work and this description largely focus on large scale political conflicts, note that everything that follows also applies to local and interpersonal disputes.

As you are about to see, the first criterion, peace, is all but obvious. The other three are not as self-evident and will therefore be at the heart of the rest of this blog in which I will be turning Lederach’s general criteria into principles that people have actually tried to put into practice since he first developed them in the 1990s.

As you are about to see, the first criterion, peace, is all but obvious. The other three are not as self-evident and will therefore be at the heart of the rest of this blog in which I will be turning Lederach’s general criteria into principles that people have actually tried to put into practice since he first developed them in the 1990s.

Peace. It is hard to imagine making much progress toward reconciliation while a conflict is still raging. That said, Israelis and Palestinian peacebuilders have been meeting and building ties across communal lines for half a century. Still, most peacebuilders are convinced that reconciliation work can only begin in earnest once a modicum of order has been achieved. The mistake so many peacebuilders made was to stop at peace when defined as “simply” the absence of war. I put simply in quotes because ending the fighting is rarely a simple task. However, stopping there and not addressing the other dimensions of reconciliation has left us with what political scientists call orphaned agreements, roughly half of which turn violent again within a handful of years.

Truth. Those of us who just lived through the 2020 presidential election know that it is possible for different people who live in the same place to have all but totally different understanding of what the world is like. As long as that is the case, it is also hard to imagine overcoming the divisions we face in the United States today. That’s one of the reasons why so many countries and, now, communities, have experimented with truth and reconciliation commissions. Put simply, until there is widespread agreement about what happened and who is responsible for past actions, it is also hard to imagine a community truly coming to grips with its divisions.

Mercy. The two final criteria take us to the heart of the matter and to the controversies that often surround reconciliation. Lederach’s use of the term “mercy” suggests that the ideas behind reconciliation have religious roots. It is a critical theological notion in all the Abrahamic faiths and is particularly important to Evangelical Christians as part of their personal relationship with God. For those who ask “what would Jesus do,” reconciliation is often not just an important issue, but the most important one in any conflict. In recent years, reconciliation has also become an important matter for people who approach conflict resolution from a secular perspective. For them, the need for reconciliation grows out of the pragmatic, political realities of any conflict resolution process (see the next section).

Whatever your inspiration, mercy calls on people to shy away from all actions that smack of vengeance, a point I will return to at several points later in this post. For now, it is enough to see that it is hard to reconcile when and if victors gloat or losers plot revenge.

Justice. That leads to Lederach’s final conclusion. It is also hard to imagine the absence of gloating or revenge-seeking if this fourth and final criteria is not met. Alas, as reconciliation’s critics are quick to point out, it often is left out or left unachieved.

Longstanding or intractable conflicts have deep historical roots and invariably involve the long term inequalities that led to what Johan Galtung called structural violence and is now encapsulated in such terms as systemic racism. True reconciliation is not possible unless a society comes to grips with the historical roots of the conflict. To use the terminology of 2020, it requires being on the “right side of history” in ways that allow the previously powerless to see their grievances met. At the same time, the interests of those who used to be “on top” can’t be ignored either. If stable or lasting peace is ever to take hold, all parties have to (at least eventually) be satisfied with the outcome.

As a result, reconciliation cannot be value neutral and privilege the positions of each and every party to a dispute. To the degree that a society has to deal with injustices perpetrated by one side over an another (e.g., racism in the United States, anti-Catholic sentiment in Northern Ireland, hostility toward immigrants in Western Europe, the legacy of apartheid in South Africa), reconciliation requires ending those injustices while leading the individuals and social groups that used to hold power to accept the new, more equal reality.

It Take (Lots of) Time

Lederach first presented this version of his thoughts in a book he wrote for the United States Institute of Peace in 1998. By that point, he had already uttered what became the most remembered one liner in the history of practical reconciliation work.

As the story goes, he was leading a workshop on reconciliation in Northern Ireland in the early 1990s. One of the participants asked him how long it would take the province to achieve reconciliation between its Protestant and Catholic populations after a peace agreement was reached. Lederach asked when the conflict began. When the workshop participant replied with the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, Lederach suggested that the residents of the province should plan on another three centuries.

Because we have learned a lot about how reconciliation works, we can probably speed up most processes so that it does not take as much time to undo the effects of a conflict as it did for the dispute itself to unfold. That said, Lederach’s comment is on target. Reconciliation takes hard work. And it takes a lot of time.

Despite the progress we have made in overcoming racism in my lifetime for example, we still have a long way to goals the events of this year so clearly attest. And more than the effects of time and the obvious structural elements of systemic racism are involved. To cite but one example, recent research on adverse childhood experiences that can set up young people up for a lifetime of challenges and failure are suffered disproportionately by children of color suggesting that the multigenerational impact of racism may be inherited physically as well as culturally.

A Systems Perspective and Right Relationships

Like many of us, Lederach has since adopted a systems perspective in his understanding of reconciliation and peacebuilding work in general. While this is not the place to explore systems theory in any detail, one of its key features can be boiled down to the fact that it gives empirical support to the cliché that what does around comes around. What I do today directly or indirectly affects what you do tomorrow and vice versa. I used the terms today and tomorrow in generic terms here to reflect the fact that our actions feed back on themselves over time.

Since that is the case, the way I deal with my adversaries (or anyone else for that matter) affects how we deal with each other for a long time to come. That has led some of us to stress the importance of forging right relationships that stress cooperation, tolerance, and humility among other things.

Revisiting History Today in Order to Reach Stable Peace Tomorrow

With the partial exception of the material on systems thinking, I could have written the section on the principles of reconciliation as part of the original Beyond Intractability entry. While the philosophical underpinnings underlying reconciliation have not changed much, our understanding of how we can turn them into practice—including how hard it is to do so—certainly have changed in the last twenty years, which is why those issues will take up most of the rest of this post.

That starts with what might seem like an odd juxtaposition. As we became more interested in reconciliation, we started paying more attention both to the longer term goals we were seeking as well as to their roots that often stretch deep into our past. To make the juxtaposition seem even odder, it makes more sense to start with the future we want to reach and then consider the role of the past in keeping us from reaching it.

Stable Peace

Kenneth Boulding was one of the true pioneers of what became peace and conflict studies. Born into a Quaker family in the United Kingdom and trained as an economist, Boulding spent the bulk of his academic career in the United States and is best known today for his idea of a stable peace.

While Boulding focused on wars between states, his definition of stable peace can be applied to just about all forms of conflict. That leads us to ask about the circumstances that make the probability of any kind of overt hostilities so small that the parties to a dispute don’t even think about exerting power over each other, seeking revenge, using intimidation, and the like. As he often put it, you can almost measure stable peace between two countries by the amount of dust that has accumulated on the war plans for invading each other in their respective defense ministries.

This is also where those orphaned agreements I mentioned earlier come into play. Years of effort went into reaching agreements like the Oslo Accords that led to Israel’s recognizing the PLO and vice versa and seemingly opened the door to stable peace between them. Those hopes, of course, have largely been dashed in the quarter century since the agreements were signed on the White House lawn.

The same holds for significant but still partial reforms like the civil rights acts of the 1960s. No one can deny the progress that was made as a result of their passage. However, as the events following the murder of George Floyd have shown us, even major reforms can only take us so far. Put simply, it is hard to imagine achieving anything that resembles stable peace without reconciliation—whether that is between Israelis and Palestinians, Whites and Blacks in the United States, or a couple trying to rebuild a relationship after a separation for whatever reason.

Facing History

It is also impossible to imagine reconciling without re-examining how events in the past created and perpetuated the conflict.

Thus, historians themselves have begun emphasizing the need to confront the problematic pasts of today’s troubled societies which Americans also saw this year in the public discussions of systemic racism. To that end, literally dozens of new organizations have sprung up that are helping us do just that. None has put the task more eloquently (or done better work in this respect) than Facing History and Ourselves, which defines its mission in this way:

At Facing History and Ourselves, we believe the bigotry and hate that we witness today are the legacy of brutal injustices of the past. Facing our collective history and how it informs our attitudes and behaviors allows us to choose a world of equity and justice. Facing History’s resources address racism, antisemitism, and prejudice at pivotal moments in history; we help students connect choices made in the past to those they will confront in their own lives. Through our partnership with educators around the world, Facing History and Ourselves reaches millions of students in thousands of classrooms every year.

It’s not just professional historians. 2020’s crises have drawn our attention to what psychologists call adverse childhood experiences or ACEs, including multiple forms of abuse and neglect. Research in the United States and elsewhere has shown that children from underprivileged and ethnically minority homes are most likely to have experienced ACEs which leaves them least well prepared to deal with the many different challenges of adult life. There is even evidence that their impact can be passed down from generation to generation through what psychologists and neuroscientist call epigenetics.

Bottom Up v. Top Down Initiatives

Reconciliation rocketed onto the peacebuiding agenda after South Africa’s TRC enjoyed so much success in the late 1990s. That led to the creation of at least forty similar initiatives around the world, most of which were anchored in the usually unspoken assumption that national governments and other elites could and should take the lead in reconciliation efforts.

There are times and places where what we refer to as top-down initiatives make sense. The experience of the last twenty years, however, suggests that reconciliation efforts are most likely to succeed when they have public buy in and thus are more bottom up than top down in nature.

One Anecdote

To see why, consider a single example.

In fall 2019, Alpaslan Özerdem, the new Dean of the Carter School of Peace and Conflict Resolution at George Mason University gave testimony about reconciliation at the opening session of that term’s meetings of the United Nations Security Council which you can watch by clicking the link below.

As he often does, Özerdem used the example of the famous footbridge linking the two sides of the Danube in the Bosnian city of Mostar as an example of a missed opportunity for reconciliation. The centuries-old bridge connecting the mostly Muslim and Christian neighborhoods had been destroyed in the fighting that racked Bosnia-Herzegovina in the 1990s. Instead of letting the two communities determine how to reunite their city, the international community simply rebuilt the old bridge depriving the residents of Mostar of the opportunity to begin rebuilding their social and emotional community while they rebuilt their physical bridge.

He contrasted Mostar’s experience with that of Coventry in the United Kingdom, where he had lived and taught before he joined us at George Mason. After the end of World War II, the citizens of that heavily bombed city decided to rebuild in a way that included reconciliation both in the way they physically rebuilt its badly damaged cathedral and in the ways that they reached out to the residents of other bombed out cities, including Dresden, Belgrade, and Warsaw which all found themselves on the other side of the Iron Curtain.

How, he wondered, could the United Nations foster projects that produced results that had the effects symbolized more like Coventry’s rebuilt cathedral and its reconciling mission than the mere functionality of Mostar rebuilt Stari most (which literally means “old bridge?”

From Top Down

Özerdem’s testimony reflects a sea change in the way we define best practices when it comes to reconciliation. He was, of course, speaking to the United Nations Security Council whose efforts best epitomize the way global elites can contribute to reconciliation efforts and peacebuilding in general. In so doing, he was also at least implicitly criticizing the widespread assumption that such efforts are best initiated elites and the national or global level.

The origins of that assumption had roots in the success enjoyed by the South African TRC whose very creation was part of a series of compromises made by the outgoing White government and the multi-racial African National Congress (ANC) during the transition to a multi-racial democracy. In that case, the fact that it was the brainchild of leaders at the highest levels contributed to its success.

Over the course of three years, the TRC heard testimony from over 22,000 individuals and applications for amnesty from another 7,000. Its hearings were televised and regularly topped the national ratings so that everyone could see both what had happened in the past and the acts of apology and forgiveness that occurred in prime time. By the time its final report was issued in 1998, the TRC had brought the vast majority of abuses to light, including those committed by anti-apartheid activists in the ANC and other organizations.

Over the course of three years, the TRC heard testimony from over 22,000 individuals and applications for amnesty from another 7,000. Its hearings were televised and regularly topped the national ratings so that everyone could see both what had happened in the past and the acts of apology and forgiveness that occurred in prime time. By the time its final report was issued in 1998, the TRC had brought the vast majority of abuses to light, including those committed by anti-apartheid activists in the ANC and other organizations.

In retrospect, it is clear that one of the TRC’s most important accomplishments was its construction of what some would call a “shared narrative” of what had happened in the past that just about everyone accepted. The Commission also did not whitewash the past. Only a small proportion of the perpetrators were granted amnesty. Many did not apply and could still technically be prosecuted, although there seems little chance of that happening almost thirty years after the fact.

The Commission certainly had its share of critics. As its own leaders, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and the Rev. Alex Boraine made clear, the TRC itself could only be a first step on would have to be a generations-long process of reconciliation which has sputtered since then.

Those limits should not keep us from seeing the bottom line, however. Those responsible for the atrocities of the apartheid era were held accountable, even if they did not end up spending time in prison.

The South African TRC’s rave (but perhaps overly positive) reviews led political leaders in upwards of forty other countries to create commissions of various sorts of their own. Unfortunately, few of them have enjoyed anything like the TRC’s success.

Most of fell short because they lacked one of the key preconditions for the TRC’s success whose importance we did not fully appreciate at the time. Much of its outgoing white elite was willing to admit to its own abuses of power. The Afrikaners, in particular, knew that they would have to coexist with the newly enfranchised majority population because there was no ancestral “homeland” that they could realistically turn to. Equally importantly was the fact that highly respected Black leaders like Tutu and Nelson Mandela made it clear that they were not interested in revenge because they understood the new South Africa’s prosperity was dependent on the economic infrastructure largely under Whites rule.

As Karen Brounéus has shown in her research on the much less well known TRC in the Solomon Islands, other commissions that were created by political elites have had less success because they did not enjoy even the degree of inter-elite understanding that existed in South Africa. As a result, few of their political leaders are likely to go through the kind of introspective reflection on their own actions that could make anything approaching a shared narrative of what had happened possible.

To Bottom Up

Özerdem’s juxtaposition of Coventry’s success with the shortcomings in Mostar points toward a conclusion that most reconciliation practitioners have now reached. More often than not, the most effective reconciliation projects are locally based and grass-roots driven.

Those pathways take communities in many different bottom-up directions. They can involve bringing people together in ways that reflect their common humanity, which I’ve seen organizations like Peace Players International do by creating basketball teams in divided cities in Israel/Palestine, Northern Ireland, and the United States. Whether it’s through sports or through explicitly created businesses like Kind Bars, reconciliation can reduce prejudice, debunk stereotypes, and limit the impact of dehumanization and, thus, the self-perpetuating cycles of violence today and, even more importantly, tomorrow.

I am personally fortunate to be part of one of the most systems efforts along those lines in which we are trying to determine and promote best practices when it comes to reconciliation. In 2019, Antti Pentikainen establlished the Mary Hoch Center for Reconciliation at the Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution at George Mason University in Arlington, VA. Pentikainen had spent the previous twenty years working in conflict zones around the world through which he has seen what happens when reconciliation efforts at the local level fall short or are lacking altogether. The moment I met him, I shifted my own engagement with the Carter School to the Mary Hoch Center because, as I told him, I had been looking to center my own work around reconciliation since I first encountered Lederach and his ideas.

The Mary Hoch Center’s team follows one of the many bottom-up paths that Özerdem (who arrived at GMU at the same time) referred to—promoting the efforts of people Pentikainen refers to as insider reconcilers. They are rarely members of national elites who typically staff truth and reconciliation commissions. Rather, they are individuals who are in the midst of the conflict themselves. Many of them are activists on one side or the other. Many also have training as psychologists or social workers with a specialty in trauma healing.

Insider reconcilers are different from most professional peacebuilders in two key respects. They themselves are parties to the dispute they are working on and they have made a conscious decision to heal the wounds the conflict has produced. In the terms of political scientist Robert Putnam, insider reconcilers understand the value of bridging social capital in which people who disagree regularly and constructively interact with each other. Insider reconcilers come in many forms, but share one thing in common. They have decided to build better relationships with everyone in their society, including those who have been their adversaries. The best evidence I could present along these lines is our role in helping create the United States Truth and Racial Healing Transformation movement earlier this month.

Insider reconcilers are different from most professional peacebuilders in two key respects. They themselves are parties to the dispute they are working on and they have made a conscious decision to heal the wounds the conflict has produced. In the terms of political scientist Robert Putnam, insider reconcilers understand the value of bridging social capital in which people who disagree regularly and constructively interact with each other. Insider reconcilers come in many forms, but share one thing in common. They have decided to build better relationships with everyone in their society, including those who have been their adversaries. The best evidence I could present along these lines is our role in helping create the United States Truth and Racial Healing Transformation movement earlier this month.

Even though we may be the only ones to use the term insider reconciler, the Mary Hoch Center is by no means unique in this respect. Build Up, which organizes the annual Build Peace conference that combines peacebuilding, technology, and the arts anchors all of its programs on the need to be both non-neutral (i.e., take stands on the “right side of history”) and non-polarizing. Peace Direct supports and trains local peacebuilders around the world, many of whom explicitly anchor their work in reconciliation. Earlier this year, Chad Ford of Brigham Young University-Hawaii’ published Dangerous Love which focuses on the power individuals and organizations gain when they “turn toward” the people they disagree with and thereby take the first step in settling a dispute. Ford himself is both an accomplished mediator who has a decade-long engagement with Peace Players International which uses basketball as a tool to bring young people in divided societies together through projects in the Middle East, the Balkans, South Africa, and, now, American cities. Ford, too, serves as a consultant for the Arbinger Institute which helps individuals see how they place themselves in psychological “boxes” that keep them from being able to take creative initiatives in their lives, including in (but not limited to) periods of conflict.

I’m also beginning to see evidence that reconciliation can be the by-product of projects that produce stable peace but focus on other social and economic goals. For example, other than the Corrymeela Center, relatively few organizations in Northern Ireland have explicitly sought to forge reconciliation among Catholics and Protestants who still live largely separate lives. However, there is some evidence that investments made in businesses that employ people from both communities made by the International Fund for Ireland or the irreverent street theater productions by Kabosh have had at least hints of reconciliation as an unintended consequence of their activities.

First Truth, then Reconciliation

The transition to bottom-up reconciliation is but the tip of the clichéd iceberg. Not only are there multiple pathways to reconciliation, is now integrated into just about everything peacebuilders do. If anything, the breakdown of reconciliation efforts that follows does not do justice to just how diverse their efforts are.

Start With Truth

The most successful efforts at reconciliation have started by establishing an agreed-upon version of the truth which is why so many of them are called truth and reconciliation commissions. As is true of much of what we know about reconciliation, the choice of words we use ends of mattering a lot.

In this case, note that I added the qualifier “agreed upon” to the word truth in the previous paragraph. This is not the place to debate whether there is any such thing as absolute truth. Instead, the key here is that the parties to a dispute have to move toward a shared understanding of the truth whose general contours are accepted by just about everyone as we saw earlier in the case of the South African TRC.

In this case, note that I added the qualifier “agreed upon” to the word truth in the previous paragraph. This is not the place to debate whether there is any such thing as absolute truth. Instead, the key here is that the parties to a dispute have to move toward a shared understanding of the truth whose general contours are accepted by just about everyone as we saw earlier in the case of the South African TRC.

In that sense, the truth component of these initiatives itself has two sides.

The first is usually pretty easy intellectually, but is almost always very difficult emotionally. We have to find out what happened to the to the people who have historically been on the weaker side of the conflict in general and to the victims in particular.

I have seen that happen recently now that systematic racism has become a “hot” political topic again in the United States. I’ve audited courses in which the professor showed graduate students postcards of lynchings of black men which were routinely sent through the United States mail as recently as the 1920s. I’ve been surprised by the fact that many of my otherwise well-educated peacebuilding colleagues knew nothing about the the forced ouster of the black-led Wilmington (NC) city council in 1898 or the Tulsa “race riots” of 1921. Last but by no means least, the recent film Green Book may have been old news to African Americans for whom the phrase “driving while black” has multiple layers of meaning. It was, however, a real eye-opener even for northern whites of my generation who never were personally exposed to the day-to-day indignities of segregation because they did not face discrimination while on car trips in the South.

The second side of uncovering the truth is much harder to pull off. To be able to move forward constructively, a community has to have what amounts to a rough common understanding of that truth.

Progress on racial issues in the United States is limited because members of the white and black communities typically have very different versions of that truth. Therein may be the South African TRC’s greatest success, because significant members of the white elite willingly took part in it. Its co-chair was a leading white religious leader with a long track record of opposing apartheid from within the system. A number of staff members came from prominent Afrikaner families. Perhaps most importantly of all, many leaders in the outgoing regime testified before the TRC and, in some cases, even requested amnesty for themselves.

Walk Through History

Surfacing the evidence about past human rights abuses elicits pain, grief, shame, and other emotions that often make it harder for individuals and groups to move forward. Therefore, reconciliation practitioners also focus on helping the people they work with see their common humanity so that they can begin charting a way forward.

Sometimes, the evidentiary process can do that. However, as we have seen frequently in the United States, many so-called truth telling initiatives tend to deepen divisions not build bridges across them. That said, there are some projects like Facing History and Ourselves that encourage people to revisit the past in a more constructive way. One of them, in particular, has always impressed me because it is simple to run and almost always has a powerful emotional impact on the people involved.

The “walk through history” is the brainchild of retired diplomat turned peacebuilder, Joseph Montville. It is best used at a session when people from both sides of a dispute have been brought together to explore options for peace but have had little or no experience working with each other beforehand. The facilitator lines up sheets of paper each of which has the date of a key event in the conflict on the floor in chronological order. S/he then puts the participants in pairs with one member from each side. Each pair then walk down the line and discusses what each of the dates on those slips of paper means to them.

Every time I’ve seen it used, the walk through history allows participants to see just how different the other person’s understanding of their shared history is. Because they have just done the exercise with a specific individual they have begun spending time with, the exercise invariably opens minds to the kinds of activities I am about to discuss. It may not create a shared sense of history in one fell swoop, but it does begin that process, which is usually all one can hpe to do early in a reconciliation process.

Digging Deep Inside Oneself

Exercises like the walk through history (and there are dozens of others) open the door to another critical component of any successful reconciliation initiative which the TRC also did extremely well. In order to truly reconcile, individuals and then societies as a whole have to reexamine some of their own most deeply held values.

We don’t have to give them up, nor should we abandon all or most of them. In my own case, I am not going to believing in or working for justice and equality across racial, gender, and economic lines.

However, I am going to put them in a new context, including asking how my own values and behaviors are contributing to the impasse my country or community or family finds itself in. The walk through history helps participants begin to make that deep internal search by getting them to see just how different their own understanding of the past and present are from that other, specific individual you have just shared your interpretation with.

In the process, at least two things happen.

First, I may well continue to disagree with the other side. Nonetheless, I have begun to develop a deeper sense of empathy with at least that other person I just did the walk through history with, and we know that the capacity to put yourself in the mental “shoes” of the “other” is a necessary component of reconciliation.

Before moving on, let me be clear here about something that people often get wrong. Empathy and sympathy are not the same. I could and should understand the racist and misogynist right wing in the United States. That does not mean that I should do anything like endorse their values. The key is to disagree with them in a way that doesn’t drive the two of us even farther apart.

Second, when I dig deeply inside of myself, I can begin to see how my own values and actions contribute to the impasse. Those of us who grew up in the 1960s often reword Eldridge Cleaver’s biting comments to White liberals in the early days of the Black power movement—if you aren’t part of the solution, you are part of the problem.

When seeking reconciliation, it makes sense to turn his words around so that they read:

You have to understand how you are part of the problem before you can become part of the solution

Trauma and Healing

It should be obvious by now that reconciliation is needed most in places that have suffered the most over extended periods of time. Invariably, those are also countries and communities where people have been dehumanized and traumatized in ways that many today find impossible to wrap their heads around—genocide, slavery, systematic hatred, and more.

In other words, reconciliation has to help people overcome those psychological wounds through a series of tools that together are referred to as trauma healing. Many of them require the intervention of trained mental health professionals. However, there are nowhere near enough of them who have expertise in the kinds of socially and politically induced trauma to help all of the victims that we can identify today. As a result, activists who work, for example, in camps housing Syrian refugees or in underserved American neighborhoods have begun experimenting with what Beyond Conflict calls a field guide for barefoot psychologists, drawing on a term the Chinese used to describe its non-professionally trained health care providers in the 1960s.

Victims are not the only ones to suffer the effects of a traumatic history. There is mounting evidence that Americans who are lashing out against Black Lives Matter activists, members of the LGTBQ+ community, or immigrants themselves suffer from something akin to trauma because they are having difficulty accepting the social changes that have swept the U.S. and countries like it over the last half century.

For all the reasons discussed so far in this post, they, too, have to be part of any serious reconciliation campaign.

Apology and Forgiveness

Reconciliation also involves more than parties to a dispute sitting down with each other, talking things out, and somehow magically finding ways to get along. While they have to do so, they also have to go farther to include some mixture of apology and forgiveness which I discussed separately when I wrote the original 2003 essay. Reconciliation experts include these two terms because they also bring us back to an essential common denominator of all such efforts—the emotional transformations that digging deeply leads to

In the South African case, the TRC was authorized to grant amnesty from prosecution (forgiveness) to perpetrators on both sides if they made a heartfelt admission of guilt that included an apology to their victims. Not everyone was eligible; applicants had to be accused of a crime that was political in nature. Not every applicant would be granted amnesty. To be eligible, they not only had to confess to their wrongdoings but show enough genuine remorse to convince the distinguished members of the commission. Perpetrators were encouraged to directly apologies to their victims and/or their victims’ surviving family members.

As Archbishop Tutu and others who participated in the most successful TRCs have pointed out, confronting the past doesn’t mean forgetting the past or somehow “getting over” that past. Instead, it is a way of dealing with the trauma of that past and finding a way to live together in a constructive and mutually beneficial way.

Policy Changes

If that’s all that reconciliation involves, I would not have devoted the last quarter century of my career to it in one form or another. In today’s terminology, the images I’ve just presented speak to a goal that lends itself to performative gestures that smack of virtue signaling at best. At worst, they can lead to situations in which people who do not understand the privilege that they are born to end up making a bad situation even worse.

That’s particularly true for someone who became a professional political scientist before becoming a professional peacebuilder. What governments do matters in at least three ways as far as reconciliation which are variations on the three main intellectual “buckets” that political scientists use to describe public policy. All of the examples here are American, but it should be clear by now that my comments apply in any place and at any time when reconciliation is called for.

Beyond Performative. One of the breakthroughs in 1960s was the attention we began to pay to symbolic policies which can be as simple as flag waving in all of its forms. Today, such actions are often seen as simply performative examples of virtue signaling that might make the people performing them feel good but actually change next to nothing.

Many argue that reconciliation is performative because it is often pursued without the adoption of reforms in the other two policy areas. To the degree that that is the case, those criticisms are justified.

However, if you take either the definitions of reconciliation I explored at the beginning of the post or the kinds of soul searching discussed so far in this section, reconciliation is more than just virtue signaling. It does include what can turn out to be purely symbolic actions like the choice of language we use (e.g. gender pronouns) or even the number of people of color we see in prominent roles on our television screens.

But, it has to go farther and literally change people’s souls, which is anything but performative. And, as you are about to see, it also has to be accompanied by concrete policy changes, too.

Restorative Justice. As the South African case shows most clearly, reconciliation rests on a relatively new kind of justice in which legal authorities are more interested in restoring good relationships than severely punishing wrongdoers. The idea of restorative justice is another example of a policy that includes an unfortunate “re” in its title. As we saw earlier with reconciliation in general, no one seeking reconciliation wants to restore the judicial patterns that existed in some earlier and presumably better period.

Rather, restorative justice processes are designed to find outcomes that solve the problems that are left behind by conventional crimes and human rights abuses alike. The international Centre for Justice and Reconciliation defines restorative justice as

a theory that emphasizes repairing the harm caused by criminal behaviour. It is best accomplished through cooperative processes that include all stakeholders. This can lead to transformation of people, relationships and communities.

In some cases, that will lead to prison terms, fines, and other forms of coercive punishment. More often, however, restorative justice practices try to bring both sides of a dispute together to right the wrong one side committed against the other.

Restorative justice comes in many forms. In some cases, it can lead to the kind of amnesty we saw in South Africa or other forms of forgiveness. More often, as the Centre’s definition suggests, it brings all stakeholders—including the accused, the victims, their families, other members of their networks, and the like—together so that they can collectively determine the best way for perpetrators to atone for their crimes. Similar logics underlie the kind of antibullying projects my grandchildren are exposed to in their schools.

Put simply, reconciliation rests on a vision of justice that includes “an eye for an eye” only as a last resort and seeks to find more constructive options moving forward that “work” for everyone involved.

Reparations, That leaves the final—and for Americans—and most controversial policy change for last. In recent years, many activists have demanded that the United States government make reparations to African Americans to pay for more than four centuries of systematic racism. Those demands have come in many forms, including different ways of determining how much is paid, by which entities, and to whom.

All, however, are based on a number of assumptions, one of which is particularly important for reconciliation. We will not be able to overcome the multidimensional effects of that history until and unless we can level the various “playing fields” that continue to keep so many people of color at the bottom of American pecking orders—including the fact that they have disproportionally borne the brunt of COVID-19.

Those of us who advocate reconciliations can be found supporting just about every point on the debate over reparations. Almost all of us are convinced that we need a dramatic redistribution of income and wealth for reconciliation and other purposes. At the same time, we tend to have doubts about proposals for reparations that would deepen resentments among many Whites and make the rapprochement that has to be part of reconciliation possible.

Going to Scale

I was frankly surprised by how much our understanding of reconciliations has grown in the seventeen years since I wrote the first version of this article, including how difficult it is to achieve. To be frank, I also learned how much we still have to learn.

I was frankly surprised by how much our understanding of reconciliations has grown in the seventeen years since I wrote the first version of this article, including how difficult it is to achieve. To be frank, I also learned how much we still have to learn.

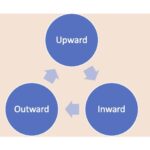

Perhaps most importantly of all, I’ve learned that we need to take reconciliation work—as well as everything peacebuilders do—to scale by bringing out the best in us which is the title I’ve given to this entire series of blog posts. I have dealt with questions of scale in an earlier post, but now I’ve come to see that we can’t truly do so unless we put reconciliation at the heart of that work.

- Inward. This is perhaps where reconciliation has already had the greatest impact on modern peacebuilding. Because it calls on each of us—including those of us who call ourselves professional peacebuilders—to dig deeply into ourselves, we see the importance of going to scale inward more clearly than we ever did. Whether it was through Rick’s explicit use of scripture or the way Emile lived peacebuilding principles, everything we’ve learned in the last twenty years or so suggests that focusing on reconciliation means that peacebuilders have to change, too.

- Outward. Both of my friends helped me see the need to scale outward and reach other communities, including the Evangelical world that Rick lived in or Emile’s network of young scientists and just about everyone in between. Reconciliation, too, is not just about convincing people we don’t agree with that we are right. Even more, it’s about entering into meaningful relationships with them, which is now more important than ever since countries like the United States are more divided than they have ever been.

- Upward. Ultimately, we do have to change public policies as suggested in the previous section. In other words, we do have to scale upwards and eventually enjoy the kind of growth that the tech companies enjoyed which got us all thinking about scaling upward in the first place. But reconciliation also suggests that there are limits to how fast we should try to scale upward. In particular, as the history of some of those Silicon Valley successes suggest, compromising one’s values—in this case speeding up reconciliation faster than we should—can lead to the kinds of ethical and other lapses that we also associated with many of those same companies.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.

Also published on Medium.