Rotary and Peacebuilding

I haven’t been writing about peacebuilding much recently, because I’ve focused my energies on the other issues that the “connecting the dots” community will have to deal with. Now, however, it is time to return to my political roots but do so through an organization whose impact I’m only belatedly coming to see—Rotary.

I’ve known about Rotary’s commitment to peacebuilding since the 1980s. I’m normally someone who looks for peacebuilding partners anywhere and everywhere and delight in bring “strange political bedfellow” together. To my embarrassment, however, I hadn’t really thought much about how organizations like Rotary could be agents for dramatic social change. As is often the case in such situations, my own blinders and assumptions got in the way. I just never imagined that an organization that drew its members mostly from the professional middle class could seriously promote the kind of social and economic change I believe in.

In fact, I only started paying serious attention to Rotary after I met Patricia Shafer in 2019 and Lisa Broderick shortly after the pandemic began. You will encounter both of them later in this post. For now, it’s enough for me to thank them for overcoming what I call my “sixties leftist hangups” and (at long last) findomg multiple ways of engaging with this amazing organization of over 1.4 million members who are scattered around the world.

My mistake.

Rotary and Service Clubs in General

Like many males of my generation, I first encountered service clubs because many of them sponsored Little League teams, perhaps including some I played on—my memory fails me on that front. My was a dentist and my mother a realtor in New London CT, and I vaguely recall that some of their friends were Rotarians, Elks, Lions, Kiwanians, and the like.

If I thought about them at all, it was as venues for local business men (and the occasional woman like my mother) to build their professional networks and do some good for the community on the side. Although I didn’t know much about what these clubs did, I knew they weren’t for me. After all, I was a new left radical not a doctor, lawyer, or owner of a small business.

While they do serve those networking purposes, they are truly service clubs whose members give an amazing amount of time to their communities and beyond—especially now that the pandemic has forced many of them to meet online and has led some to think in terms of a mission-focus rather than a geographical one. Most date to the early twentieth century—in Rotary’s case 1905.

Of them all, Rotary International is the largest and the most global. Its 1.4 million members belong to 46,000 clubs, spent about 47 million hours doing service projects in 2021, and donate more than $330 million a year to service projects around the world. Intriguingly, only about a third of Rotary’s members are American which almost certainly makes it the most international of these organizations.

Rotary is also amazingly decentralized. Local clubs determine their own agendas within the very broad parameters laid out as Rotary International Goals, including promoting peace, eradicating polio and fighting other diseases, providing clean water and sanitation, protecting the environment, developing local economies, supporting education, disaster response, and protecting women and children.

As such, it causes overlap with United Nation’s sustainable development goals which should not come as a surprise, since Rotary has had a working relationship with the UN since 1945. Although it only admitted women members in the 1980s, Rotary has taken firm stands and made considerable progress in diversifying itself—and my sixties self should point out that it still has along way to go, as do we all.

Rotary and Peace: An Overview

Once I finally to take Rotary seriously, I realized that its biggest strength is that it is solutions oriented. I’ve never heard a Rotarian downplay just how serious the problems we face are, ranging from long-term issues like climate change to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. At the same time, I’ve rarely heard a Rotarian complain about the actions or intentions of other people—including those I know they disagree with.

Perhaps because Rotary’s origins lie in the business community, its members tend to focus on what might work, whether that means raising money or helping out on divisive issues in their communities.

Perhaps because Rotary’s origins lie in the business community, its members tend to focus on what might work, whether that means raising money or helping out on divisive issues in their communities.

Furthermore, if you look at what it calls “our causes” which I listed a few paragraphs ago, you can see that Rotarians tend to see the intersectionality of the wicked problems we face. In fact, I’ve been amazed by how deeply most of them see the ways that those problems causes and consequences are inextricably intertwined.

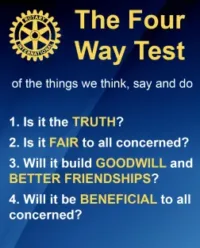

That holds even more for its “four way test” which clubs and their members use in determining when, where, and how to act:

- Is it the TRUTH?

- Is it FAIR to all concerned?

- Will it build GOODWILL and BETTER FRIENDSHIPS?

- Will it be BENEFICIAL to all concerned?

Flagship Programs

That’s easiest to see in its three flagship programs in the peacebuilding side of its work.

Peace Fellowship Program. Since its launch in 2002, this program has funded over 1,500 fellows who now work in 115 countries . Most of the fellows are fairly young and are fully funded to pursue a master’s degree in peace and conflict studies at one of five universities on four continents. Older students who may already have advanced degrees or who cannot commit to two years away from home enter a shorter certificate program at a university in either Uganda or Thailand. In both cases, the program includes more than formal classroom instruction. Even the certificate students spend time networking and developing projects of their own that they implement when they return home or, in some cases, end up in some third country.

Peace Fellowship Program. Since its launch in 2002, this program has funded over 1,500 fellows who now work in 115 countries . Most of the fellows are fairly young and are fully funded to pursue a master’s degree in peace and conflict studies at one of five universities on four continents. Older students who may already have advanced degrees or who cannot commit to two years away from home enter a shorter certificate program at a university in either Uganda or Thailand. In both cases, the program includes more than formal classroom instruction. Even the certificate students spend time networking and developing projects of their own that they implement when they return home or, in some cases, end up in some third country.

Partnership with IEP. I should have paid more attention to Rotary as soon as I first learned about its partnership with the Institute for Economics and Peace a few years ago. IEP was created by the Australian philanthropist, Steve Killelea, to promote research on peace and has arguably become the most influential peacebuilding think tank in the decade since it issued its first Global Peace Index in 2008. The relationship with Rotary was made possible when IEP developed a second measure, the Positive Peace Index, which, unlike the first data set, focused on what led to more peaceful rather than more violent societies. Its eight “pillars of positive peace” include high levels of social capital, a good business environment, effective governance, the free flow of information, social trust, and the like, all of which overlap with Rotary’s own service goals.

Late in the 2010s, leaders of the two organizations agreed to form a strategic partnership in which Rotarians would try to put into practice the lessons learned from IEP’s research. In essence, Rotary became the “think tank’s” first “do tank.” For my purposes, the most interesting and promising project is the Positive Peace Activator’s program which provides activists around the world with about twenty hours of classroom training in peacebuilding which culminates in each one of them developing a plan for implementing positive peace which they will carry out over the course of the next two years.

Late in the 2010s, leaders of the two organizations agreed to form a strategic partnership in which Rotarians would try to put into practice the lessons learned from IEP’s research. In essence, Rotary became the “think tank’s” first “do tank.” For my purposes, the most interesting and promising project is the Positive Peace Activator’s program which provides activists around the world with about twenty hours of classroom training in peacebuilding which culminates in each one of them developing a plan for implementing positive peace which they will carry out over the course of the next two years.

Rotary Action Group for Peace. Rotary also has a number of action groups that support work on one or more of its many causes in ways that transcend what any individual local or online club can do. Thus, in 2012, it endorsed the work of the action group for peace which is based in Portland OR and was inspired in large part by the remarkable Al Jubitz and his family foundation. To square the circle, Al and I first met through Beyond War in the 1980s, and my mentors then suggested that we begin our local initiatives with the Rotary Club in our home towns. I didn’t see the point. Luckily for my team, one of my colleagues was already an active Rotarian.

Rotary Action Group for Peace. Rotary also has a number of action groups that support work on one or more of its many causes in ways that transcend what any individual local or online club can do. Thus, in 2012, it endorsed the work of the action group for peace which is based in Portland OR and was inspired in large part by the remarkable Al Jubitz and his family foundation. To square the circle, Al and I first met through Beyond War in the 1980s, and my mentors then suggested that we begin our local initiatives with the Rotary Club in our home towns. I didn’t see the point. Luckily for my team, one of my colleagues was already an active Rotarian.

My mistake again.

Other Promising Initiatives

Note that these three flagship programs are all either undertaken or endorsed by Rotary International’s leadership. Remember, though, that Rotary is an amazingly decentralized organization in which individual clubs—whether organized locally or online—largely determine what they take on as service projects.

And this is the way I’ve largely plugged into Rotary projects because they hold the most promise if and when they can be taken to scale. Consider these four examples.

Youth and Peace in Action. I began taking Rotary seriously after I met Patricia Shafer who did the Peace Fellows program as a mid-career professional. It changed her life. By the time we met, she had already created New Gen Peacebuilders which developed curricula for high school students in the United States and a number of other countries. With the support of the Alliance for Peacebuilding, IEP, and the Rotary regions covering the Middle Atlantic and Southeastern states (as well as parts of the Caribbean), Shafer and her team launched Youth and Peace in Action at the beginning of this academic year. In its initial report on its first year ten days ago, we learned how programs were already underway at 318 schools. About 7,000 students and close to 100 teachers took basic courses in peacebuilding. Even more impressive were the more than 45,000 hours that those students devoted to projects that they defined themselves to meet peacebuilding needs in their own communities.

Youth and Peace in Action. I began taking Rotary seriously after I met Patricia Shafer who did the Peace Fellows program as a mid-career professional. It changed her life. By the time we met, she had already created New Gen Peacebuilders which developed curricula for high school students in the United States and a number of other countries. With the support of the Alliance for Peacebuilding, IEP, and the Rotary regions covering the Middle Atlantic and Southeastern states (as well as parts of the Caribbean), Shafer and her team launched Youth and Peace in Action at the beginning of this academic year. In its initial report on its first year ten days ago, we learned how programs were already underway at 318 schools. About 7,000 students and close to 100 teachers took basic courses in peacebuilding. Even more impressive were the more than 45,000 hours that those students devoted to projects that they defined themselves to meet peacebuilding needs in their own communities.

Portland Peace Initiative. Portland OR has had a troubled history as far as race relations is concerned, which many of us around the country saw as the city struggled to deal with protests after George Floyd’s murder. Rotarians and others in the community were quick to respond with a slew of activities that have come together as the Portland Peace Initiative. It has organized a series of “tables” or open discussions in which local officials from the police and other parts of city government come together. Gretchen and I attend a region-wide weekly Rotary planning session (virtually, since we are on the east coast) in which members from local clubs discuss what they are doing in the community, have regular speakers, and so on. The larger Portland Peace Initiative is spearheaded by the pastor of the largest Black church in the city, activists in the Police2Peace community led nationally by Lisa Broderick, and others. We’ve been sitting in on those meetings for the last four months and have been impressed not only by the commitment of individual Rotary members but by the tangible progress they have made in building working relationships with BIPOC entrepreneurs in some of the city’s most troubled neighborhoods.

Portland Peace Initiative. Portland OR has had a troubled history as far as race relations is concerned, which many of us around the country saw as the city struggled to deal with protests after George Floyd’s murder. Rotarians and others in the community were quick to respond with a slew of activities that have come together as the Portland Peace Initiative. It has organized a series of “tables” or open discussions in which local officials from the police and other parts of city government come together. Gretchen and I attend a region-wide weekly Rotary planning session (virtually, since we are on the east coast) in which members from local clubs discuss what they are doing in the community, have regular speakers, and so on. The larger Portland Peace Initiative is spearheaded by the pastor of the largest Black church in the city, activists in the Police2Peace community led nationally by Lisa Broderick, and others. We’ve been sitting in on those meetings for the last four months and have been impressed not only by the commitment of individual Rotary members but by the tangible progress they have made in building working relationships with BIPOC entrepreneurs in some of the city’s most troubled neighborhoods.

As I’ll argue in the final section of this post, Rotary will not solve all of our country’s problems on its own. However, both of these first two projects have convinced me that its solutions-oriented approaches can be taken a long way and that these two projects could easily be adapted and taken to scale on other issues (in the case of Youth and Peace in Action) and in other communities (in the case of the Portland Peace Initiative).

Indeed, some of us are beginning to explore how to do just that.

E Club for Peace. Like much of the world, Rotary had to go virtual once the pandemic hit two years ago. Some of its peacebuilders had already headed in that direction when they created a pioneering online-only E Club of World Peace after a face-to-face conference in 2016. Patricia and Lisa (who is its incoming president) first told me about the club, and Gretchen and I finally joined early this year and haven’t missed a meeting since.

E Club for Peace. Like much of the world, Rotary had to go virtual once the pandemic hit two years ago. Some of its peacebuilders had already headed in that direction when they created a pioneering online-only E Club of World Peace after a face-to-face conference in 2016. Patricia and Lisa (who is its incoming president) first told me about the club, and Gretchen and I finally joined early this year and haven’t missed a meeting since.

The first thing we noticed is that we knew next to no one in the club, which is remarkable given the fact that I’ve been doing this work full time since the 1980s. We were also surprised by how electric the meetings are, especially since they start at 9.30 in the evening eastern time, by which point I’m usually heading for bed!

As an online club, it is hard for the group to do specific projects since its members are scattered throughout the United States and in a handful of other countries. Still, we have already found ways to raise money for refugees who fled the war in Ukraine and helped convince Rotary International to devote its disaster relief resources entirely to Ukraine in the first days and weeks following the Russian invasion. Members have continued to reach out to their fellow Rotarians both in Ukraine and in Russia, making it one of the few groups that I’m aware of that has maintained constructive relationships with both people on both sides of the dispute.

How Rotary Changed My Book and My Life

As a student activist in the 1960s and then when I rediscovered peacebuilding with Beyond War in the early 1980s, I could never have imagined myself being part of Rotary or any other service organization of its ilk. Too much of my self-definition was wrapped up in being a “sixties Leftist” to be comfortable with hanging out with Rotarians. Yet, that’s what I find myself doing.

I spent the first sixteen years of my professional career teaching at Colby College in Waterville ME. It never occurred to me to connect with the local Rotary club even though it now appears that its president is a former colleague. Similarly, I had never thought about joining either the one in Falls Church (our mailing address) or McLean (where our house actually is) during the first twenty-nine years that I’ve lived inside the (in)famous Beltway.

My mistake again.

As my therapist does keep reminding me, the sixties were a long time ago, and maybe I should reconsider that part of my self-definition. Rotary has definitely helped.

It really does a terrific job of two things I’ve always thought were important. First, as I’ve already noted, it focuses on solutions rather than the problems. Second and even more importantly, it does an amazing job of appealing to people of all ideological stripes, something we so desperately need in our polarized society.

It has also thrown the plans for finishing my book on Connecting the Dots into disarray, if only a bit. I had planned to focus on young activists, most of whom are under forty. For good or ill, most of the folks I’ve met in these Rotary circles are well past 40. We are, for example, nowhere near the oldest people in the E Club. Similarly, Lisa and Patricia are younger than we are, but they haven’t seen 40 in a while.

So, part of the book will focus on intergenerational leadership, in particularly on how we geezers (oops, I mean senior citizens) can learn from the young people we work with, like the high school students in YPA or the mostly young Positive Peace Activators.

What Rotary Isn’t and Can’t Be

Rotary is not only answer to the problems facing the United States and the world as a whole. It can’t be.

It also won’t be the only place I engage with those problems.

In fact, I’ll still do more elsewhere.

And, in part because it is solutions oriented and apolitical, Rotarians spend less time than I would like dealing with structural inequalities and the realities of power, whether in the United States or the rest of the world.

Despite Rotary International’s commitment, not that many local clubs are deeply involved in peace projects, including the local clubs in all of the communities I’ve ever lived in.

I also don’t expect the edgier activists I work with to share Rotary’s almost total obsession with what works.

Nonetheless, it is a breath of fresh air that will add a lot not just to the peacebuilding world I’ve been in for the last half century but in the broader movements for social change that have gained newfound popularity and legitimacy during the course of the last two tumultuous years and the the two tumultuous decades that came before them.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.

Also published on Medium.