Reconciliation, Race, and the United States

Like many Americans, I’ve been worrying about the resurgence in both overt and more subtle forms of racism in this country. I’ve been fascinated, too, by the discussions of everything from reparations to the renaming of streets and buildings here in Virginia and elsewhere in the South.

My thinking has been sparked, too, by the creation of George Mason’s School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution’s Mary Hoch Center for Reconciliation and a not so important example in my personal life.

New Takes on Old Music

Let me deal with the not so important one first. I got a new pair of noise reduction blue tooth headphone and a streaming music service and decided to download lots of 1960s protest movement which I listen to on my daily walks. They are nostalgia inducing, but anything by the Freedom Singers and songs like Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young’s Teach Your Children and reminded me that we thought we committed ourselves to the long haul and would not end up with challenges like “OK Boomer” from our grandchildren—a theme I’ll take up next week.

The Freedom Singers reprised one of the civil rights movement anthems that made it clear that theirs and ours would be a long struggle.

Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young struck a similar theme in a different way by talking about the ways children and parents learn from each other and how that changes over time.

Reconciliation: A New Take on Tough Questions

The more important change at least for my professional life came when I met the leaders of the newly created Mary Hoch Center for Reconciliation at GMU. I’ve been interested in the subject since I first read John Paul Lederach’s writings on the subject more than 20 years ago and have been frustrated how little serious attention the topic has gotten beyond some spectacular but still limited efforts like South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

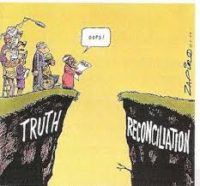

As this cartoon suggests, the commission did an amazing job of ferreting out the truth of what had happened under apartheid but, understandably, made a lot less progress on the reconciliation side of things. In particular, how did it create spaces in which South Africans could continue to deal with the pain of their past and truly find ways to live constructively with each other.

That’s precisely what the Mary Hoch Center and its director, Antti Pentikainen, intend to do. Even though as his name suggests, Antti is not American, the divisions in the US are at the top of his agenda. I’m drawn to its work because of its understanding, first, that reconciliation has to revolve around what he calls insiders who are part of the dispute and take the initiative to resolve it by breaking the cycle of hatred and conflict. I’m also drawn to Pentikainen’s sense that reconciliation is part of an infinite game that has no end point when it is “completed” and can be crossed of one’s mental to do lis

But, what would reconciliation look like in the United States in the light of the events of the last few years? That is something the center will be addressing in the weeks to come.

At the very least would have to take the four key concepts Lederach wrote about a generation ago:

- Peace

- Truth

- Justice

- Mercy

Critical for our purposes are the final two criteria. Obviously, we need peace or an end to the violence that has been on an upsurge. And, we need to know the truth about what has happened in our country. Unlike South Africa in the 1990s, there is no shortage of evidence about our past—assuming we care to look at it.

And in the United States?

All too often in discussions of reconciliation or other policy alternatives in the United States, we have given justice and mercy short shrift along with of the other values that go along with it, including apology and forgiveness. Thinking about the Mary Hoch Center (and the Freedom Singers and Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young) led me to see that reconciliation can point us toward positive social change.

Racial justice has to involve something like reparations, but even that might not be enough. It will require addressing the lasting impact of racism on American society in its institutions, structures, norms, and policies as the current discussion of anti-racist approaches suggests. Mercy involves coming to grips with what happened. In particular, that means that the white community has too see the importance white privilege still has, even for someone like me whose family arrived decades after the civil war and the end of slavery. More importantly, it will involve profound cultural shifts that would lead to equally sweeping policy changes that would include—but not be limited to—some form of reparations.

Here, my new friend Antti is right. We won’t get there unless we intentionally break the cycle of suspicion, hatred, explicit and implicit bias, and everything that scholars like my GMU colleague Tehama Lopez Bunyasi and her co-author, Candis Watts Smith, get at in their new, wonderful book, Stay Woke.

It is important to remember that the Freedom Singers reunited to appear in the Obama White House and made the Obamas sing along. It is important, too, that Graham Nash made this video of Teach Your Children in conjunction with the March for Our Lives movement.

They remind us, too, of something Rev. Desmond Tutu said when he issued the TRC report in South Africa. “Reconciliation isn’t cozy.” It requires all of us to dig deep inside ourselves, take responsibility for what happened in the past, and take ownership for building a more peaceful, egalitarian, and cooperative future. It’s that ownership of the future that leads to the chasm in the cartoon at the top of this post.

It’s More Than Talk

Reconciliation won’t provide all the answer. However, focusing on it will take us beyond the currently popular and vitally important efforts to promote better discussions across ideological and other lines of division.

Reconciliation does require the kind of discussions that organizations like Living Room Conversations or Better Angels are hosting. But it has to go much farther.

All of us—starting with me (and you)—have to explore our deepest values and do our part. It requires the steadfastness of the Freedom Singers and the irony of teaching your parents (or, now, grandparents) well.

And, as Tutu and Graham Nash also reminded us, it requires remembering which side justice is on.

Oh, and by the way, the young people who deride us with “OK Boomer” are probably right. To see why, all you have to do is look seriously at what the leaders of my generation have done with power both in government and in the private sector.

But that’s the subject for another day.

For now, I’m just delighted that Antti and his team have me (re)focused on reconciliation here in the US.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.

Also published on Medium.